Teacher, leader, adviser, shopper

Manitoba First Nations education architect Shirley Fontaine helped push generation's worth of advancements

Advertisement

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$1 per week for 24 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $4.00 plus GST every four weeks. After 24 weeks, price increases to the regular rate of $19.95 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.99/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19.95 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 08/06/2019 (2471 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

Prominent in scholarly and political circles, Shirley Fontaine’s sudden death on April 26, after a brain aneurysm and a series of strokes, shocked a vast network of Indigenous Canadians.

Their loss is, in many ways, Manitoba’s loss, too.

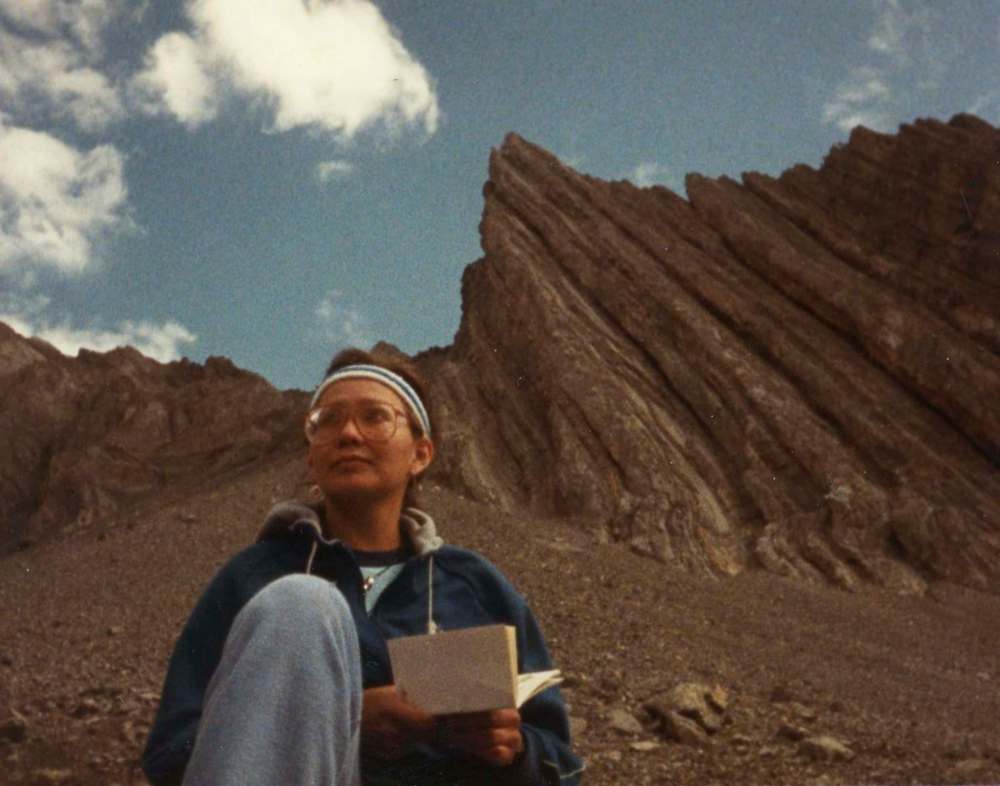

Her eldest sister, Sharon Shuttleworth, will host a family gathering on Sunday, which would have been Fontaine’s 61st birthday. The little girl who loved books and grew up to become a teacher, educator, policy analyst, writer and political adviser would have loved the gesture.

In her 40-plus-year career, Fontaine moved the needle as one of the province’s best-known architects on First Nations education and sovereignty.

She was born Shirley Malcolm, on Ebb and Flow First Nation in the Interlake, on June 9, 1958, one of eight children.

“Shirley always had a book with her, no matter where she went, and she would spend hours in the bedroom, reading novels, books, whatever she had. I recall my mother asking her to assist me with housework, yardwork and Shirley would say, ‘I will come as soon as I’m done,’ but, of course, there were always more books,” Shuttleworth said.

Fontaine began her career working with the Manitoba Indian Education Association in the late 1970s. By the early ’80s, she marked her first milestone as one of youngest First Nations instructors at the University of Manitoba, teaching her Anishinaabe language.

Her leadership qualities were recognized early and used often. She was closely connected with just about every advance in First Nations education in Manitoba over the last generation.

As education director with the Assembly of Manitoba Chiefs, Fontaine was among those who conceived and established the Manitoba First Nations Education Resource Centre. She helped develop the Assembly of First Nations’ policy to advance control of education, and was a key adviser on curriculum material promoted in provincial schools by the Treaty Relations Commission of Manitoba.

She was also a political force at the local, regional, provincial and national levels, conceiving and carrying out numerous policy initiatives and preparing speaking notes for chiefs and grand chiefs. Internationally, she was regarded as an ambassador for education and she travelled extensively, presenting the challenges and successes of Manitoba First Nations education to audiences in North America, New Zealand, Australia and Peru.

Her traditional name — Kah Beh Zhi Gway Dung Pineshee Kwe — fit her: Thunderbird Who Speaks Once Woman. She drew strength from her traditional Anishinaabe spiritual and ceremonial practices.

“Another thing I was always mindful about after her passing was that, in many ways, she and her friends, there were a lot of women that led our organizations and movement. They may not have been holding titles like chief or grand chief but they were the ones that animated many of the things that made advances for our people,” said her son, Brennan Manoakeesick.

Virginia Arthurson is one of those women; Cynthia Bird is another.

Bird, a consultant based in Calgary, and Fontaine met when they both landed their first jobs after university, and they formed a lifelong friendship.

“Being in the position she was, she always had to be so diplomatic to work with so many different personalities. Different people would come with different agendas. She would manage to work things through and help people stay focused on the work,” Bird said.

“She was always so graceful with the way she conducted herself.”

Fontaine was also known for the twinkle in her eye. When she entered a room, she seemed to bring a zing into the air. That joie de vivre showed up in her sense of humour and her fashion sense. In short, she had panache.

“She really did, you know,” Bird said with a chuckle. “She won’t be afraid to wear the hats that go with the (outfit), the purses, the heels, shoes, everything.”

Another close friend recalled the coping mechanism they both shared to maintain grace under pressure: retail therapy, with Fontaine its master shopper.

“We went to Tadoule Lake one time, when we were doing our community consultations to see if they were OK with the process and how we wanted to start it,” Arthurson said.

The assembly had hired the two to develop the framework for an education agreement nearly 30 years ago, and the job involved repeated trips and long meetings on the 60-plus First Nations from the U.S. border to Hudson Bay. Tadoule is the northern-most First Nation in the province.

“She said, ‘Let’s go shopping,’” Arthurson said.

The Northern store was basically the one-stop shop.

“We were in there and she said, ‘Come see, look at all these raw silk T-shirts. And they’re on sale! For $10!’ I started laughing and I said, ‘Only you, Shirley would find raw silk T-shirts in Tadoule.’ Then, of course, we hauled all these shopping bags (home) on a little plane,” Arthurson said.

At the time of her death, Fontaine was the associate executive director at the resource centre.

Beyond all the serious work matters, Fontaine’s sense of fun showed through in countless photos, including the one the family used for her obituary. “The way I look at her, her smile (in the photo), she appears to be looking at someone, from her body language, like she just finished teasing someone and was waiting for their response,” said Brennan.

Midway in her career — after a first marriage and two sons who she and her ex-husband raised in an amicable custody arrangement — she fell in love and married the love of her life, Earl Fontaine. They had 17 years together, revelling in their blended family.

Earl, too, died suddenly, just before Christmas 2018.

Fontaine doubled down after that.

“She always had the big picture, the long game in mind. Part of the challenge for us as a family is that less than 10 weeks before she passed, her and I sat down and she talked to me about her 10-year plan,” Brennan said.

“I was asking her if she would consider moving toward retirement. She basically scoffed at me and said, ‘No.’”

She had planned to finish her PhD this summer. She had made plans for a grand family vacation this summer to California, to tour Alcatraz and Disneyland. Christmas was to be spent in Hawaii.

“All these things that she still wanted to do,” her son said.

alexandra.paul@freepress.mb.ca