Private trove, public treasures

Passionate art collector John Crabb gave Winnipeggers access to his beloved Walter J. Phillips works, helped create Leo Mol Sculpture Garden

Advertisement

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$1 per week for 24 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $4.00 plus GST every four weeks. After 24 weeks, price increases to the regular rate of $19.95 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.99/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19.95 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 29/06/2019 (2450 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

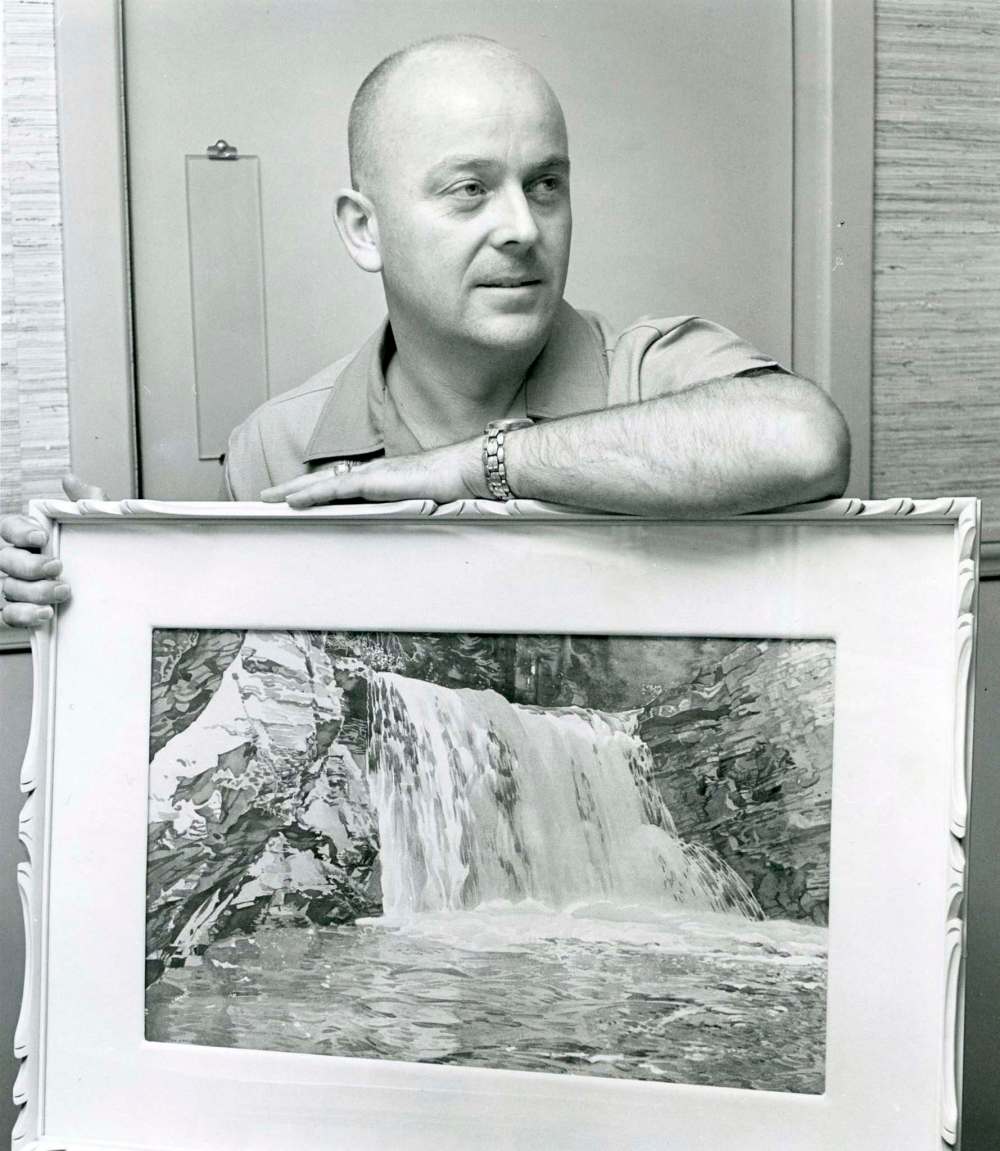

Some people are merely art collectors. John Crabb was a passionate collector to be sure, but he was also a knowledgeable art protector and presenter.

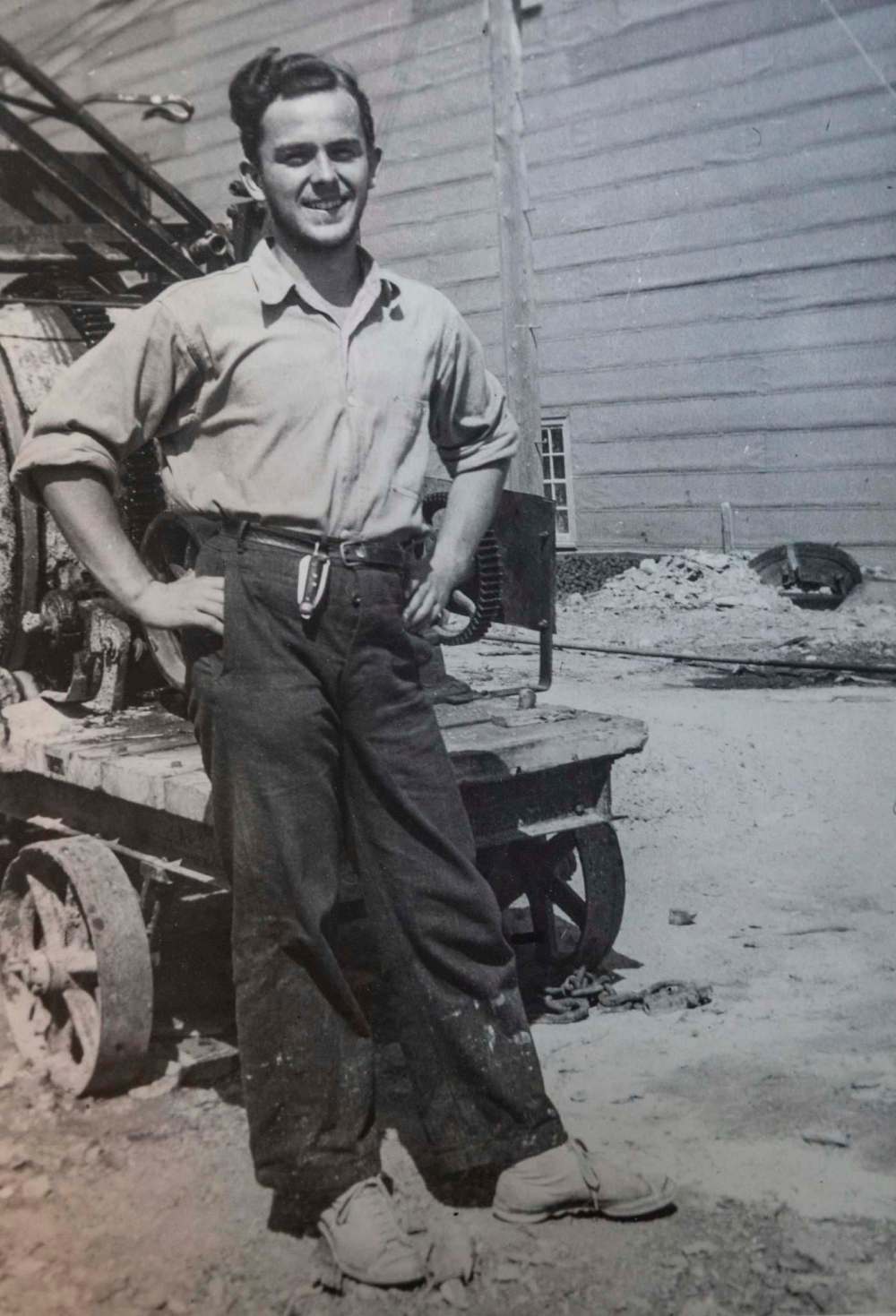

The Winnipeg businessman, who died on Feb. 25 at the age of 89, was a lifelong art appreciator involved in the creation of the Pavilion Gallery and Leo Mol Sculpture Garden in Assiniboine Park.

He was the world’s foremost collector — an estimated 1,000 pieces — of western Canadian artist Walter J. Phillips’ works.

David Loch, owner of Loch Gallery, said Crabb “was a leader and not a follower.”

“He collected things he wanted to collect. He had amazing taste and a lot of knowledge… and he was a smart businessman, too. It was really mind-boggling to me that John amassed that collection.”

Loch said Crabb put together items from his Phillips’ collection for a tour across the country in 1970 to commemorate the 300th anniversary of the Hudson’s Bay Co.

Decades later, Crabb donated the bulk of his collection to help create the Pavilion Gallery in Assiniboine Park, which opened in 1998. A second-floor wing at the gallery is named in his honour.

Crabb told the Free Press in 1967 that he had been able to collect about 400 of Phillips’ original coloured woodcuts, oil and watercolour paintings and original wood engravings.

“There are still a few pieces missing, which I hope will turn up,” he told arts writer Peter Crossley. “The more people that see it, the happier I’ll be.”

By the time Crabb donated the art to the Pavilion Gallery, his Phillips’ collection had grown to about 1,000 pieces, including 360 watercolour paintings.

“John recognized it was the right thing to do after a lifetime of collecting,” Loch said. “People can go and see what a genius Phillips was and John Crabb made that possible because he recognized Phillips before anyone else did.”

In a 2002 video produced by R.W. Sandford, the Banff Centre and the Pavilion Gallery Museum, Crabb said: “There isn’t anything I’ve spent more time on in my entire life than putting the Phillips collection together.”

“It perhaps wasn’t an obsession, but in another sense it was because I was terribly afraid if I didn’t do it somebody else wouldn’t do it and it wouldn’t be there for people to enjoy. I felt everybody should do something for others and leave something behind them. If I’ve left the Phillips collection for other people to enjoy, then that is my epitaph.”

Crabb was born in Winnipeg, the only son of Herbert Philip and Doreen. He attended Queenston School before going to Quebec’s Bishop’s College and Sedburgh College. He returned to Winnipeg and graduated from St. John’s College School.

He was beginning to take architecture at the University of Manitoba before he changed direction and left school to join the insurance company of Oldfield, Kirby and Gardiner before, in 1956, becoming a self-employed general insurance agent, later founding several companies.

Crabb married Donna Jean in 1958, and they were together for 35 years and had three children — Dave, Sheryl and Douglas. He was married to Marilyn Baker for the last 22 years of his life.

Crabb’s daughter, Sheryl Thomson, said it was interesting being raised in a house full of art.

“We were never allowed to have a poster on the wall,” she said, laughing. “We all had artwork in our bedrooms. But it gave me an appreciation for art.

“He would never have lived in an open-concept house; there would not have been enough walls for art.”

Dave Crabb said the house itself was something his dad had wanted to add to his collection for a long time.

“He helped out at a party for a well-known Winnipegger who owned the house when he was a kid,” Dave said.

“He said, ‘One day I want to own that house,’ and years later he did. That house was super-important to him.”

His father’s love of art also became part of family vacations, he said; long road trips invariably included a visit to an artist in another province.

Baker said her husband became interested in Phillips when, as a child, he helped his father fold reproductions of Phillips’ watercolour artwork to create Christmas cards sent to family and friends.

“That probably sparked his interest in Phillips, but he liked all sorts of art,” she said.

“He liked Canadian art more than English. He had art from the Group of Seven at one point and he used them to finance his collecting frenzy.”

Sheryl said her dad kept the bulk of his art in the remodelled attic of their house, which he called “his gallery,” but he didn’t want it to stay there.

“He wanted his collection to go somewhere that the public would see it. He didn’t want it stuck in a vault somewhere.”

That, however, didn’t mean it was easy for him to part with the pieces he donated to the Pavilion Gallery.

“He kept the watercolours he liked. And he said it would have been easier to sell his children then send the Phillips to the gallery.”

Ray Phillips, Walter’s grandson, said he and other family members sold some pieces to Crabb.

“He certainly was the driving force behind getting my grandfather’s work out to the public,” he said.

“My grandfather was well respected already, but what (Crabb) did didn’t hinder my grandfather’s work… who knows what would have happened if John Crabb didn’t come around?”

Phillips said it was too bad that Crabb never got to meet his grandfather. Walter J. Phillips died in July 1963, just before Crabb started building his collection.

Crabb was also a great supporter of the Winnipeg Sketch Club, donating space in a building he owned on Assiniboine Avenue for almost three decades until 1997.

Loch credits Crabb for finding the building on St. Mary’s Road that is still home to his gallery.

Crabb also collected English silver objects, included Vesta cases, dating from the 1700s to the 1900s, as well as art created by other western Canadian artists, including Winnipeggers Mol and Clarence Tillenius.

“I’ll remember my dad as a man who gave me everything I could want: a good home, we always had food on the table and access to the Winter Club,” Dave said.

“He gave me the tools to grow up.”

Besides Crabb’s wife, daughter and two sons, he is survived by four grandchildren.

kevin.rollason@freepress.mb.ca

Kevin Rollason is a general assignment reporter at the Free Press. He graduated from Western University with a Masters of Journalism in 1985 and worked at the Winnipeg Sun until 1988, when he joined the Free Press. He has served as the Free Press’s city hall and law courts reporter and has won several awards, including a National Newspaper Award. Read more about Kevin.

Every piece of reporting Kevin produces is reviewed by an editing team before it is posted online or published in print — part of the Free Press‘s tradition, since 1872, of producing reliable independent journalism. Read more about Free Press’s history and mandate, and learn how our newsroom operates.

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.