Consternation under the canopy Elm and ash trees as old as Winnipeg deliver a beautiful outdoor ceiling — but fear for their future is growing as they are unable to withstand the ravages of voracious pests and disease

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$1 per week for 24 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $4.00 plus GST every four weeks. After 24 weeks, price increases to the regular rate of $19.95 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.99/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19.95 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 14/06/2019 (2465 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

The thing about trees is they are best viewed from below.

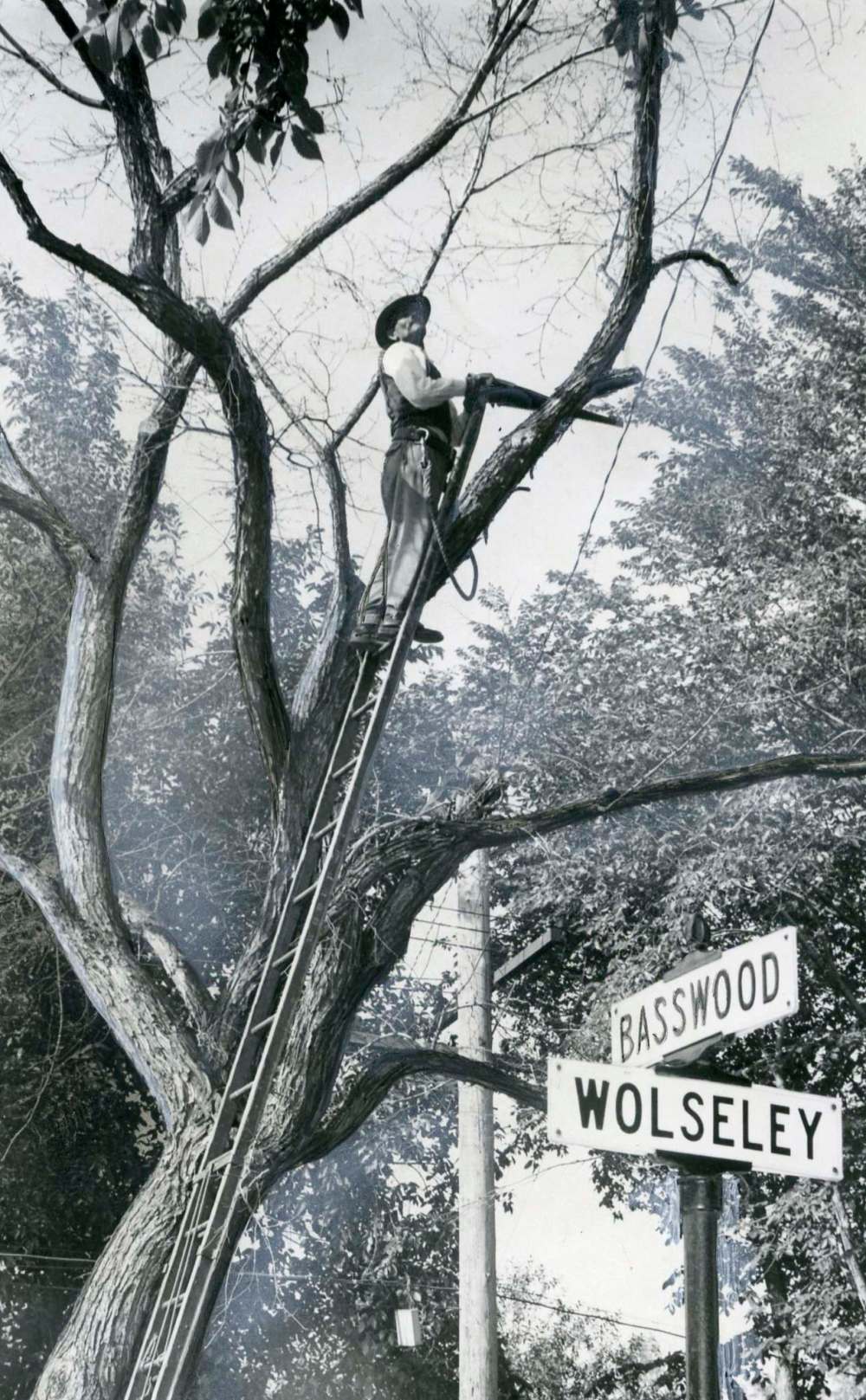

Ariel Gordon and I are lying on our backs on the boulevard in front of her Wolseley home, gazing up at her tree in the May morning sunshine. It’s a beautiful old elm, its long limbs gracefully reaching for her porch.

We all have our tree. Trees, actually. Gordon crunched the numbers; there’s roughly 11 trees for every Winnipegger.

“I love that we’re so firmly outnumbered by trees,” she says.

Gordon has spent a lot of time thinking about trees, and what they mean. The author has just released a collection of essays, Treed: Walking in Canada’s Urban Forests. On this morning, we’re thinking about elms — those giants of our old neighbourhoods that have watched over generations of Winnipeggers. The elms that were planted by people who saw a wide-open prairie and envisioned a forest.

“If you’re going to change a place, if you’re going to colonize a place, and one of the ideas is to put in parks and trees, that is maybe the only good idea to come out of that exercise,” Gordon says. “I still sometimes wonder, I think on the conundrum of what it means to live on the Prairies, and be born and raised on the Prairies and have never seen the tall grass prairies.

“This would have been tall grass prairie,” she says of her neighbourhood. “There would have been islands of aspen parkland and bur oak and there would have been the riverbank forests. That’s where you would have seen these hardwoods — the oaks, the elms, the ashes.”

Winnipeg’s elms have shaped our civic identity. They’ve also demonstrated, vividly, the risks inherent in planting large monocultures of the same species.

Our tree canopy is one of our most valuable assets. But was it also our biggest urban-planning mistake?

“Winnipeg isn’t very much different from any other city in North America that is in the north temperate zone,” says Martha Barwinsky, the current forester for the City of Winnipeg, when that question is put to her.

“American elm has been a well-used urban tree. It is native, it is very hardy, and it is very tolerant of urban conditions. A lot of cities in Canada and the northeastern United States planted elm because of that. There were monocultures of elms everywhere. We are really limited to the types of trees we can grow successfully here, that will thrive here. That’s one of the reasons the elm is so important to us. We know it’s tough. We know it will survive in our climate.”

OK, so, maybe “urban-planning mistake” is a little harsh?

“Yes,” says a laughing Monica Giesbrecht, a landscape architect with HTFC Planning and Design. “If you think about it, those trees have served our community for well over 100 years. If you think about the return on investment for planting that tree for whatever dollar amount it was at the time, they’ve more than paid for themselves.”

Trees are, and have always been, an important part of urban design — but we don’t always necessarily notice how hard they work for us. In fact, sometimes we stop noticing them at all. American botanists James Wandersee and Elisabeth Schussler coined a term for this phenomenon: plant blindness. But in the face of a changing climate, trees will have an increasingly big role to play in cities.

“The world is changing so there’s a huge amount of pressure on our urban centres for resilience and adaptability to climate and climate extremes,” Giesbrecht says. “Winnipeg happens to be one of those cities who lives through those extremes, and it’ll fluctuate even more over time. Urban street trees and an urban forest are a huge mitigating factor. They are one of the tools we can use to adapt to climate change and make cities livable.

“It’s been proven, for example, that street trees located in the proper locations around buildings will reduce energy consumption, especially air conditioning in the summer by 20 to 30 per cent, so it actually affects your bottom line,” she continues. “Beyond that, trees produce oxygen so they improve air quality, especially in cities that have air quality challenges. In addition to that, it’s very well documented that a human connect to nature improves mental well-being.”

And, of course, trees are beautiful, providing colour on an otherwise drab concrete and asphalt urban canvas.

“Recent studies have proven that the economic viability of a city is directly tied to its esthetic and livable qualities,” Giesbrecht says in agreement. “People are looking to live in nice places.”

Making Winnipeg a nice place to live was top of mind for people such as George Champion, who moved in 1907 from Toronto to Winnipeg where he served as the superintendent for the parks board for almost 30 years. He envisioned a city of parks, and made the blueprints for many of our most famous ones — Assiniboine and Kildonan among them — a reality.

But Champion was also a big believer in boulevards, mostly because the way to the park should be as nice as the park itself. Broad, tree-lined boulevards were every bit as important a feature of the early City Beautiful Movement as buildings. The big, strong, fast-growing American elm was readily available, and it could create those architectural cathedral arches on Winnipeg’s streets — much more suitable than Manitoba maples, which Champion considered filler trees.

Winnipeg’s beautification had begun before Champion’s arrival, however. The March 17, 1905, edition of the Manitoba Free Press had a story on head gardener D.D. England’s “lengthy but interesting” report detailing the successes of the parks board’s year-long beautification campaign. Nearly 18 kilometres of boulevard had been constructed, and some 6,000 elm trees had been planted, mostly by property owners.

“These trees will always be a valuable asset to the property and the street, especially the sunny side,” England said. “In larger cities they recognize this to such an extent that they are removing stone flags from the sidewalks and are planting trees at great expense.”

By the end of 1908, Winnipeg boasted 138 kilometres of boulevard and 20,000 trees.

But our elm canopy isn’t just composed of tidy, evenly spaced boulevard trees. Settlers were also planting their own seedlings, transplanted from the wild riparian forests that run alongside our tempestuous rivers.

In other words, it’s impossible to explore the future of our urban forest without looking back at Mary Ann Kirton Good and her riverbank trees.

Mary Ann Kirton was born in the Red River Settlement in December 1841, and grew up a green thumb. When she married James Good in 1860 and settled in what is now Wolseley, she carefully planted elm saplings from the banks of the Assiniboine River around her new house in an effort to make it a home.

The city grew up with Mary’s trees, and also literally around them. One of her elms was right where a rapidly growing city wanted to put a new road. Wolseley Avenue ended up going around what would come to be known at the Wolseley Elm — a great big, triple-trunked elm tree on the city’s tiniest park. Think of it as an early traffic calming circle, although people were anything but calm about it. Someone even tried to blow it up, once.

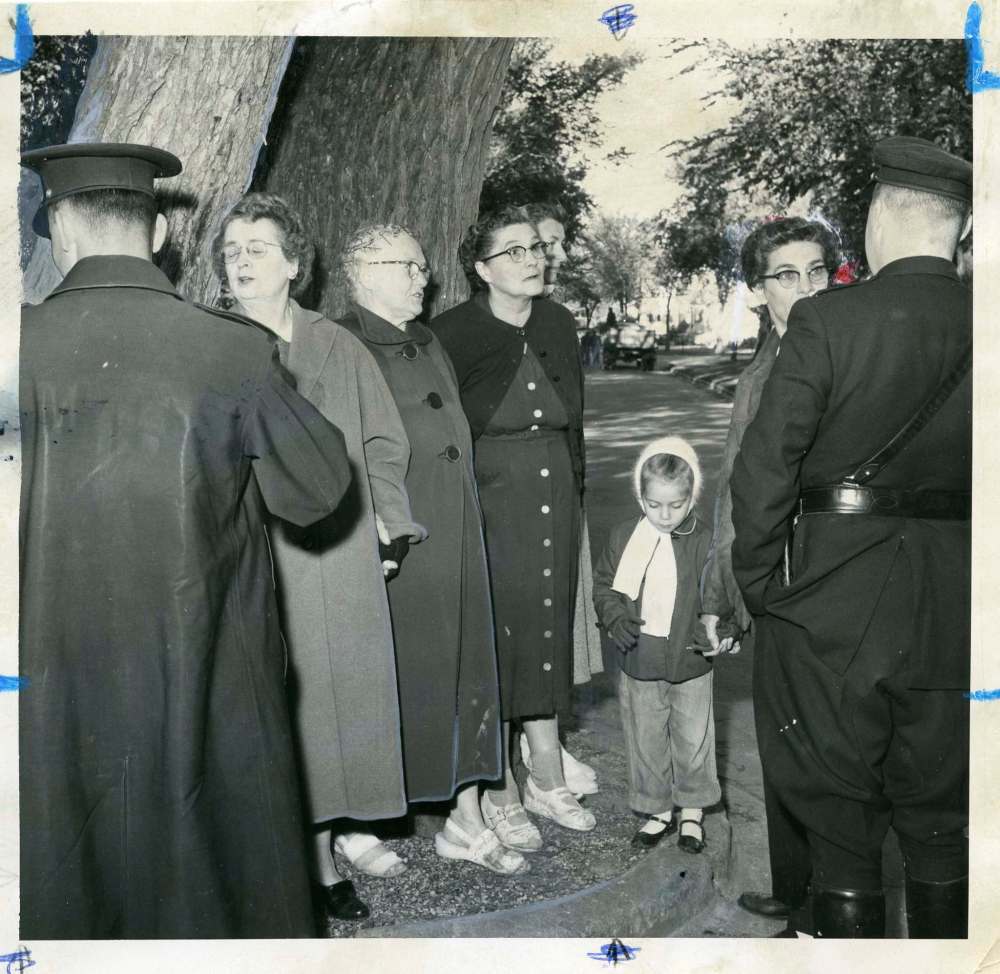

In the 1950s, the Wolseley Elm became a site of activism. The Wild Women of Wolseley — kindred spirits of Mary Ann Kirton Good — formed a human barricade around it in an attempt to save it from the city’s efforts to remove it, catching the attention of Life magazine. Winnipeggers are passionate about their trees.

The Wolseley Elm was finally cut down in 1960. It had outlived Mary by almost 30 years.

Elsewhere in the city, our elm canopy was growing up bright and fast and strong. But the story of Winnipeg’s elms isn’t just a coming-of-age tale. It’s also a survival story. By the 1970s, Winnipeg was home to North America’s largest urban elm forest. That same decade, our city’s oldest deciduous friends would enter a long, expensive fight for their lives.

Dutch elm disease arrived in Winnipeg in 1975 in the St. John’s Ravenscourt/Wildwood area.

It’s a cruel disease, caused by a fungus that chokes out the tree’s vascular system, preventing it from taking up water or nutrients. The fungus is spread by elm bark beetles who ferry the spores around. But humans are also responsible. Dutch elm disease didn’t get to North America from Europe on its own.

While the alarm was sounded in the 1970s, people were expressing concern about the risks of monoculture planting and Dutch elm disease long before its arrival in Manitoba.

An End to Elms? And Oak Street Started It read a headline on the front page of the March 8, 1956 edition of the Winnipeg Free Press.

“The stately elm, which has graced the boulevards of Winnipeg and countless other North American cities for lo, these many years, may soon give way to rival varieties,” the story begins. “At least, that’s what’s going to happen if Thomas R. Hodgson has his way.”

Although that makes him sound like the antagonist in some sort of knock-down drag-out Oak vs. Elm showdown, Hodgson was, in fact, Winnipeg’s superintendent of parks. He was concerned elms made up a staggering 90 per cent of the city’s boulevard planting and was advocating on behalf of the residents of Oak Street, who had, the year before, petitioned the parks board about planting a little variety on their then-new boulevard.

The board had refused, on the grounds it might set a “dangerous precedent.” Apparently, 1956 attitudes toward diversity in society extended to trees, as well.

But Hodgson was eyeing an elm-ravaging disease that was spreading west. Dutch elm disease had already arrived in North America in the 1930s, and was detected in Quebec in the 1944. By the time it hit Winnipeg in 1975, diversity didn’t seem like such a threatening idea.

It took visionaries to imagine an urban forest in the middle of the Prairies, and it would take visionaries to save it. One was Mike Allen, who developed the city’s pioneering DED Management Program, which still exists today.

Dutch elm disease was on everyone’s mind at the time, says Allen, who still works in Winnipeg as an arborist and a tree diagnostician.

“There was a lot of publicity we put in the paper,” he says. “We had community meetings scattered around to bring people up to date with the knowledge we had about Dutch elm disease because people were noticing, quite easily, their elms failing. When you have a 70 or 80-year-old elm and suddenly it’s dying, they’re concerned.”

More than that, people felt helpless; they wanted to find something they could hold on to in terms of control, he says.

When asked if planting thousands of a single tree species was a mistake, Allen offers some perspective.

“In Winnipeg, we’re at a bit of an advantage because we are learning from other cities that have already suffered all the losses.” – City of Winnipeg forester Martha Barwinsky

“When these trees were planted, there was no such thing as Dutch elm disease. At the time, there was no inherent problems with the American elm. With the invasion of the beetle from Europe, all of sudden there was a big impact. The trees started to lose their leaves and everything else, and then of course they were failing and dying. You can always say in hindsight the way we should have done it, but at the time it was appropriate to grow them. They were fast-growing, they were safe, and they were very beautiful.”

In 1989, the city’s canopy was rocked by the worst wave of Dutch elm disease since its first appearance in 1975. By August of ’89, the elm body count had already numbered 12,000 in southern Manitoba since the spring of that year. Millions of dollars have been spent fighting it.

Getting Dutch elm disease under control took a collaborative effort between the city, the province, the University of Manitoba and community organizations such as Coalition to Save the Elms, founded in 1992.

“In Winnipeg, we’re at a bit of an advantage because we are learning from other cities that have already suffered all the losses,” Barwinsky says. “We can see what’s worked and what hasn’t worked. That’s a big part of our DED management program; we were able to learn from the past mistakes of cities that didn’t get to disease management fast enough, or there wasn’t a desire to manage that disease or preserve that canopy.”

As a result, many of our mature elms are still standing. “Yes they are,” Allen says. “And that’s remarkable.”

But just as the city was finding success managing Dutch elm disease, a new threat to our urban forest appeared on the horizon: a metallic green beetle from Asia with a destructive appetite — not for elm, but for ash.

For almost 10 years, a moratorium was placed on planting American elm trees. And so, like many other cities, Winnipeg focused on beefing up the population of its next-best tree, ash. Green ash, in particular, had many of the same advantages as the American elm — it was another native, hardy, large shade tree.

When the emerald ash borer arrived in North America in the early 2000s, industry professionals were understandably worried. Another tree, another monoculture, another specific scourge.

The pest was first detected in Windsor, Ont., in 2002; less than a decade later it had spread throughout Ontario and parts of Quebec. By 2017, it had arrived in Winnipeg likely spread here, again, by infected firewood.

While no bigger than a grain of rice, the insect is the ash tree’s grim reaper. The prognosis for Winnipeg’s ash canopy is dire, and Barwinsky is frank.

“We know the ash population is going to die. We are going to lose our ash canopy,” she says. “That’s what’s making our DED management program that much more important because we know we can manage it and preserve a portion of our elm canopy. No other city in North America has carried on the kind of program we have, in large part because of the value placed on our American elms.”

Gerry Engel is the president of Trees Winnipeg, formerly known as the Coalition to Save the Elms. Although, in many respects, the old name remains the organization’s mandate. In order to maintain an “acceptable level of loss” of elms — about two per cent annually — Dutch elm disease needs to remain top of mind. Recently it’s been about three to five per cent, or roughly 5,000 trees.

“We have to ensure that the diseased trees that are identified every year are removed,” he says. “What would be my wish, if I could have one, is a rapid-removal program that removes diseased trees before the fall migration or first migration (of the beetle), but at the very least what we need to aim for is removal before the spring or second migration.”

For the past four years, the city has been running its removal program year-round to catch up on DED removals. “We’ve taken care of the backlog and we managed to remove the trees marked last year,” Barwinsky says. “We will have almost 100 per cent of removals completed by the end of May.”

Elm and ash now make a combined 60 per cent of the city’s boulevard and park trees; within that, 27 per cent are elm and 33 per cent are ash. While Barwinsky is hopeful about the future of the elm, ash is a different story. The emerald ash borer has completely annihilated ash populations in other cities — even proactive ones, with budgets and plans.

Barwinsky points to Minneapolis-St. Paul, where a significant number of ash trees are dead where they stand, awaiting removal. And that’s a problem. Ash trees that die from emerald ash borer become public safety risks. Unlike the elm, which are a more structurally sound tree even in death, ash trees start failing. They lose limbs. They become unstable and unpredictable, making their removal dangerous.

“Ten to 20 years down the road, that’s what we’re going to be faced with, so we’re trying to get a head start on it and be proactive because we know logistically, considering all the challenges we’ve had keeping up with the number of removals for DED, it’s going to be that that much more with EAB,” she says.

Engel agrees. “Considering all the other threats we have now, from infill housing development to the EAB, both biotic and abiotic challenges ahead of us, but we do know we can control DED to reasonable levels, and we really have to focus on that.”

Those challenges put into stark relief the hazards of monoculture planting. Barwinsky points to New York City, which lost its elms to a wave of Dutch elm disease, its maples to Asian longhorn beetles and now its ash canopy to emerald ash borer.

“We just keep making the same mistakes by planting these monocultures,” Barwinsky says. “If anything, what’s happening in urban forestry, with the introduction of these invasive species, there has certainly been a strong push to move away from a monoculture planting to a much more diverse urban forest,” she says. “With that, we have a lot of challenges, but we end up having a more resilient urban forest because we don’t have complete canopy wipeout from one pest.”

“We’ve been awaiting its arrival,” Engel says of emerald ash borer. “When you think about the whole business of trees, the nurseries and their investment in certain trees, even when we knew EAB was a threat we were still planting ash trees. DED, we didn’t really get it yet when it arrived. We wanted to get trees planted.

“So, wind the clock forward to 2019, we know that if anything is going to save us going forward, it’s diversity. We speak to that in so many ways. In trees, that’s the answer.”

Two summers ago, I watched city workers cut down an elm across the street.

It didn’t look healthy so it wasn’t a surprise when it was finally marked with the telltale spot of safety-orange spray paint. Not all trees marked for removal are infected with disease. Sometimes they are just old. But knowing something — or someone — is going to die seldom makes it easier to say goodbye.

There’s a blunt efficiency about the removal process. The leafy crown tumbles down first, followed by its larger limbs. A chainsaw is used to make strategic incisions into the trunk so workers can carefully pull it down to earth, avoiding houses and neighbouring trees. And then, right there in the middle of the street, limb and leaf are unceremoniously loaded into a wood chipper. That part struck me as weirdly indecent, like watching someone be dismembered and then immediately cremated.

I felt momentarily silly for feeling sad. But it is an emotional moment. Trees are beautiful living and breathing things, even though we sometimes think of them as objects, as architecture, as infrastructure — beautiful, sure, but not alive.

“You watch them grow, and they’re part of a cyclical thing that reminds you of life and watching life end — I don’t care if it’s a person or a tree — it’s sad,” Giesbrecht agrees. “You think about the things those trees have seen over 100 years. It reminds you you’re part of a larger system.”

During the Dutch elm disease epidemic of 1989, Mike Allen took bereft residents’ calls. “I’ve had people crying over the phone,” he told the Free Press in August of that year. “They say, ‘Somebody put a red mark on my tree. I’ve known that tree for 40 years.’

“It’s a personal relationship they have with that tree and when it’s gone it’s almost like a death in the family.”

Many people who live in the city’s older neighbourhoods have mourned a canopy filled with holes, the growing swaths of open sky. Maybe Winnipeggers feel a sense of kinship with our mature trees because we see ourselves in them. Those old trees represent our resilience. They represent survival.

“I think they’re part of our DNA,” Engel says. “They’ve been so critical to us. The feel you have going into summer, and the beauty and the comfort, to walk down a street that’s tree-lined and all of nature that exists around the trees. And in the winter, I love trees naked more than I like them leafed out, quite frankly. You see the woodiness, the architecture of the tree — that’s the most unbelievable appearance of the tree. To walk those same streets in winter gives me a whole other feeling of protection and comfort.”

“I think all Winnipeggers, it’s something we identify as being a Winnipeg thing,” Giesbrecht says. “That perfect shot down a River Heights street with the cathedral arch — that’s Winnipeg. For those of us who aren’t 100 years old, it’s home.”

Those archways are also connected to colonialism, and that complicates some Winnipeggers’ feelings about them.

“It is a colonial thing,” Gordon says. “I was reading a 1930s-era book on the native trees of North America and it was like, ‘every settled place had an archway of elms.’ And that’s a nice thing. It’s nice to think our city has a link to everywhere else through its trees. But then you think about terminology. Settled. That’s colonial language. It’s a weird thing. But the elms. I’m a settler in this place. The elms in this configuration are a settler thing. But I will still mourn them when they’re gone.”

Letting go of those old trees will inevitably mean letting go of a certain image of our city. The iconic cathedral archway, the vision George Champion, Mary Ann Kirton Good and so many others had of a nice place to live, is our past. It will not be our future.

“We will not get that incredible canopy with a diversity of trees, that archway we’re so used to,” Engel says. “The only way to create that is with a monoculture. I’m not saying there isn’t a place in the landscape for monoculture plantings — there is. But on our main boulevards and in your average communities, we need to be encouraging diversity.”

Winnipeg is not the only city grappling with how to create a more diverse tree canopy a century later. Giesbrecht says there’s a discussion in urban forestry around the 10-20-30 rule, which says an urban tree population should include no more than 10 per cent of any one species, 20 per cent of any one genus, or 30 per cent of any family, which is obviously a big change from “all elm all the time.”

“The big debate is about how fine-grain that is,” Giesbrecht says. “So, does that mean every street has to have 10 different trees? Or, does that mean every second street can have a different tree and you’re still establishing the same kind of diversity? Or, it’s about changing how you do things. Maybe you don’t plant trees on boulevards at all anymore, although I would argue that one of the biggest problems in Winnipeg is heat-island effect, which is gaining heat from the sun on paved surfaces, so we’d want to shade out our paved surfaces.

“But it could make it such that you develop a palette of trees that is acceptable and encourage people in their own properties and provide a kind of incentive. Those trees can be a little less rigidly planted.”

The palette of trees Barwinsky is planting with includes hackberry, maple and bur oak, as well as smaller trees such as Ohio buckeye and northern acclaim honeylocust, along with ornamentals such as Japanese tree lilac, amur maple, amur chokecherry and rosybloom crabapple. “Linden is great, but we have to be careful we’re not planting too many lindens in one neighbourhood,” she says. “Poplars, too, recognizing that they just aren’t as long lived as other trees.”

And we shouldn’t offer our elegies for the American elm just yet.

“There are elms that have been bred for tolerance to DED,” Barwinsky says. “But we’re also planting American elm, primarily in neighbourhoods where DED hasn’t been an issue or there’s a monoculture of ash. We’re introducing elm here and there.”

Ultimately, Barwinsky says, we will have to shift our thinking of what a treed boulevard looks like.

“It’s not going to be that uniformity we’re so used to seeing with our elms. It’s going to look more like a balanced urban forest,” she says. “Really, aesthetically, it’s going to be more interesting — that’s the way I look at it.”

“We’re not getting 70-foot giants again — that’s not going to happen,” Allen says. “But we are getting a highly diverse planted population of trees that have a high tolerance to pests and disease.”

Back in Wolseley, Ariel Gordon and I are admiring The Nicest Elm in Winnipeg, according to an arborist she met. It’s a handsome, hulking elm near the corner of Palmerston and Wolseley. We’re marvelling at all it has lived through, at all it has seen, at all it has survived.

An older woman, out for her morning walk, passes us.

“It’s a great tree, isn’t it?” she asks, although it’s more of a statement than a question.

Yes, it is a great tree. But then, they all are.

jen.zoratti@freepress.mb.ca Twitter: @JenZoratti

Jen Zoratti is a columnist and feature writer working in the Arts & Life department, as well as the author of the weekly newsletter NEXT. A National Newspaper Award finalist for arts and entertainment writing, Jen is a graduate of the Creative Communications program at RRC Polytech and was a music writer before joining the Free Press in 2013. Read more about Jen.

Every piece of reporting Jen produces is reviewed by an editing team before it is posted online or published in print – part of the Free Press‘s tradition, since 1872, of producing reliable independent journalism. Read more about Free Press’s history and mandate, and learn how our newsroom operates.

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.

History

Updated on Saturday, June 15, 2019 9:22 AM CDT: Fixes typo