A run for the border A perilous, frozen trek into Canada was the only option for three terrified migrants. The alternative was to face death in their home country

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$1 per week for 24 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $4.00 plus GST every four weeks. After 24 weeks, price increases to the regular rate of $19.95 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.99/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19.95 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 10/03/2017 (3291 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

EMERSON — All is quiet on the northern front.

It’s the middle of the night, just a stone’s throw from the Canada-U.S. border, and the temperature has fallen to -23 C.

There’s only a breath of wind, but it’s the kind of night where the cold is not weather anymore, it’s the enemy.

So maybe this isn’t a good idea, after all, to sit in a parked car from 11:30 p.m. until dawn hoping to document the first moments for asylum seekers as they set foot on snow-coated Canadian soil.

Surely, no one will arrive on this night, when even sitting in a parked car with the engine off — any border jumpers will likely be heard before they’re seen — is a bone-chilling exercise in patience.

A Free Press reporter is in one car and a photographer is in another. We’re parked on the northeast edge of town, along the railway tracks which, in recent days, have been a common path for refugee claimants — most originally from east Africa — who sneak over the border in the dead of night.

The previous night, one unmarked vehicle, likely occupied by members of the RCMP’s Integrated Border Enforcement Team, sits on the top of a crest overlooking the rail border-crossing.

Now, it seems, there are more watching. An RCMP officer approaches to politely ask about our business.

“We have to know,” he says, “because there can be so many people out here.”

Over two days, however, the only other media outlet to stake out the border is a two-man crew from Russia’s RT News, the reporter based in Toronto, the camera man from Washington. RT has a distribution reach of 700 million households in 100 countries, and the reporters spent the day interviewing residents and RCMP about the asylum-seeking phenomenon.

But they’ve had a long day, and leave after a couple of hours.

It seems everyone knows their roles in this game of cat-and-mouse.

“Do you want any coffee?” Stephane the RCMP officer asks after we tell him who we are and what we’re doing here. “I’m going to Tim Hortons.”

How Canadian is that?

The 700 or so residents of this once-quiet community are hyper-aware of the situation that’s been thrust upon them. It’s not just the invasion of media from across the globe, poking and prodding around their town, either.

Most have become unofficial watchdogs, checking out or reporting anything that looks out of sorts. As dawn arrived the day before, a municipal snowplow driver noticed we were parked near the Emerson Inn. He stopped and got out of his vehicle.

“Are you waiting for people to cross?” he asked.

“Yes, why?”

“I watch for them, too,” he replied, noting that he keeps an eye out for anything suspicious before climbing back into the vehicle and moving on.

The purpose of our stakeout, however, is not just to locate migrants crossing the border, but to chronicle their first few days in this country. Where are they coming from? How do they navigate their way in a strange land? What are they seeking?

Nearing the end our second overnight watch, it appears the bitter cold has deterred even the most desperate to leave the United States; the only moving forms we spot in the darkness are the dozens of deer that quietly invade Emerson every night.

Around every other corner, deer in the headlights.

And then, shortly before 6 a.m., while idling on the crest abandoned by the RCMP vehicle, the phone pings.

It’s a text from Free Press photographer Phil Hossack.

“Meet me at the hotel NOW!!!”

•••

The next few minutes is a blur.

Upon arrival, a man is being escorted by an RCMP/IBET officer into an unmarked car in the Emerson Inn parking lot. Two other men are seated in the back of the vehicle.

Hossack saw the man now being placed in the police car a few minutes earlier, aimlessly crossing the main street into town pulling a suitcase on wheels. He was wearing only jeans, sneakers, a hoodie under a light jacket and a tuque.

“You need help?” Hossack asked. He nodded, yes.

He said his name was Maurice and was showing signs of hypothermia.

“Am I in Canada?” he asked more than once, clearly exhausted. “What’s going to happen?”

Maurice jumped into the Free Press vehicle and began warming his hands over a heater vent. Within a matter of seconds, the RCMP officer arrived.

Across the street, four people are walking in front of the Maple Leaf Motel. A man and a woman were wearing luminous vests. Two other men looked up as the Free Press car approached, looking scared and bewildered.

Like deer in the headlights.

The man and woman wearing the vests say they are morning walkers who have, lately, been serving as unofficial guardians of asylum-seekers.

“We just do it,” the man says. Both he and his companion decline to give their names.

“I don’t agree with how they enter, but they’re people. And I’m not going to let them freeze.”

Their first order of business is to get the strangers out of the cold. They knock on the motel’s front door and are met by Frank and Faye Suderman and their 10-year-old dachshund Benny.

The Sudermans have managed the motel since last summer. And they, like many here, are concerned not just about their own safety, but also that of the men, woman and children arriving at their doorsteps in increasing numbers.

“It’s heartbreaking, it’s horrible,” Faye says. “It’s so sad that they can’t come across the border legally. And many don’t know if they’ve crossed the border. And just imagine the confusion; you’re in the white desert. And you don’t know where to go and what to do. It’s a nightmare.”

“I don’t think they know where they are when they get here,” she adds. “Maybe we should have put a sign there. Everywhere I drive around, when I see bumps in the snow I’m actually worried. I hope that’s not a Somalian who died. It’s a terrible feeling. They’re taking such chances all the time.”

This is one of those times.

Before entering the motel lobby, one of the men makes a sign of the cross over his torso. Both men, wearing parkas, are shaking.

Inside, the two identify themselves as asylum-seekers, originally from Bangladesh. They both lived in New York City after entering the U.S. on working visas.

They both have identification cards: Shahadat Hossain, 38, and Subir Barman, 40.

They say they attempted to cross the border into Ontario near Buffalo earlier in the week, but failed. They searched the Internet and social media and decided Emerson might be a better bet.

After nearly two days on a bus, they got to Grand Forks and then took a cab to the U.S. side of the border. They were dropped off at 2 a.m. One had a phone, but the GPS didn’t work. They wandered in the bitter cold for nearly four hours.

“We didn’t know where is the border, left or right,” Shahadat says, his teeth still chattering. “We saw several lights here.”

Despite his discomfort, Shahadat spills out his story. He tells of his father, Abul, being murdered back home, and how his family warned him not to return to Bangladesh, where his wife also lives.

It’s more difficult to understand Subir. Hardly surprising after the last few hours.

“Were you ever scared that you might be stranded out there in the dark?

“Still,” he replies.

Subir’s reasons for seeking asylum are less clear.

“I cannot go back to my country,” he declares.

Of course, this is no time for an in-depth interview. But two prevailing messages emerge.

“I want to live,” Shahadat says. “I want to stay here for the rest of my life.”

For these two desperate men from Bangladesh, the warmth and temporary sanctuary of the Maple Leaf Motel at daybreak doesn’t change the reality that their journey is far from over.

What now?

“I don’t know,” Subir replies.

It takes about 15 minutes for the police officer to arrive. Subir and Shahadat will be screened by RCMP before they’re handed off to the Canadian Border Services Agency office at the border.

A few minutes later, a municipal emergency vehicle with volunteer paramedics aboard arrives at the CBSA office, followed by an ambulance. There are, surprisingly, no injuries for them to treat.

It turns out that during what had earlier appeared to be a quiet night, Maurice, Shahadat and Subir were only three of 19 asylum-seekers who made it over the border in the past few hours, including the two men Maurice joined in the back of the police car.

All have been taken back to the border, where they’re being processed before being taken to Winnipeg. Emerson’s residents awaken and go about their business.

As though nothing happened.

•••

Shahadat perches on a cot at the Salvation Army’s Booth Centre, taking a seat next to a folded grey blanket, a plump white pillow, and all his possessions: a backpack, a few items of clothing and a cell phone with no service.

Did he bring anything else? Shahadat, 38, shakes his head, no. He had books, he says, but he had to leave them in the United States. It would have been too much to lug them through the snow.

Everything he owns now can fit into one stuffed backpack, resting against a wall at the Henry Avenue shelter.

Usually, this first-floor room serves as an event space. But as more asylum-seekers came through the doors last week, it had to be converted. Eight migrants slept here last weekend in two neat rows of cots.

This is where Shahadat and Subir live now. It is nothing like their homes in Bangladesh. The walls are painted institutional blue, festooned with bits of Christmas detritus: a plastic Santa Claus, a red-and-white garland.

It’s spartan. It’s also clean and safe, and meals are served three times a day. For now, that’s enough.

“They are helping us with everything,” Shahadat says. “How many days I will stay here, I don’t know. But I can sleep.”

It’s four days since the two men trudged through knee-deep snow to get to Emerson. They still have all of their fingers and toes, which they worried about when they set out for the Canadian border in the cold.

Frostbite is how they learned about Manitoba. In January, they saw a news story about two asylum-seekers from Ghana who spent hours staggering through frozen fields. They lost chunks of flesh to the merciless Prairie cold.

For Subir and Shahadat, refugee hopefuls living in New York, the story was both a warning and a beacon of hope.

“He lost his fingers, but he’s alive,” Shahadat says. “If I cut off my fingers, I’m still alive. But if I’m deported from the U.S. or Canada, then I will be killed. So I think it will be better if I lost the fingers, I don’t care. I want to save my life.”

So in New York on Feb. 27, they spent some of their dwindling cash on winter boots before boarding a Greyhound that pulled into Grand Forks 46 hours later. A taxi driver agreed to get them closer. Then they walked five bitterly cold kilometres in darkness.

They didn’t lose any fingers. They made it to Canada safely. Now, they begin the second part of their long, fear-fuelled journey.

The first 48 hours on Canadian soil slide by gently. Border officials in Emerson gave them food and water; they were “very nice,” Shahadat says. That evening, a driver from the Manitoba Interfaith Immigration Council’s Welcome Place brought them into the city, to the Booth Centre.

What happens next won’t be as miserable as trudging through snow, but it could be more numbing. There will be paperwork, more paperwork and then weeks — or months —of waiting. Canada’s immigration bureaucracy plods at its own pace.

Subir has his first meeting with immigration officials. It is just an initial contact, a chance to express his intention to make a refugee claim. One unsettling word comes up in the conversation.

“They are talking about deportations already,” Subir says, with a worried frown.

This is not the life that either Shahadat or Subir envisioned for themselves. They are both professionals: Shahadat is a fire-safety inspector, Subir an aircraft engineer. In Bangladesh, he worked on Bombardier Dash-8 planes at a local airport.

Subir had never considered leaving the country. He had done well for himself, his wife and their two children. Facebook photos show glimpses of a life filled with family, lots of friends and sunny days in the park with the kids.

But sectarian violence has rocked the South Asian country, and it quickly tore Shahadat and Subir’s lives apart. They didn’t know each other there, but what happened sent each of them reeling, fleeing for safety on the other side of the world.

Shahadat is Muslim. Subir, 41, belongs to Bangladesh’s Hindu minority. As extremist Islamic militant groups exploded in the country, slaughtering opponents and ransacking Hindu temples, both became vocal critics of terrorist groups.

“We are trying to have a democratic country,” Subir says. “(Shahadat) too, we are the same.”

Four years ago, Islamic extremists in Bangladesh published a hit list with the names of 84 secular writers. Many of them have since been murdered, often targeted by machete-wielding assailants on busy streets. Their families are in danger, too.

In 2015, Avijit Roy was hacked to death in Dhaka, an attack that also left his wife gravely injured. Last year, a law student who’d begged for police protection after weeks of threats was murdered in his apartment.

Shahadat, who blogged his criticism of the militants under a pen name, is on the hit list, he says. Anonymous letters arrived at his home: “Be careful, you will be the next,” they read. “You will be killed within a few days. Be ready.”

It wasn’t an idle threat. In early 2016, knife-wielding assailants attacked him and his father near their home; Shahadat raises his sweater to show where they stabbed him, just above his right hip. That time, they survived.

He fled to the United States. His wife quit her professional job and went into hiding.

For a while, he thought the situation in Bangladesh might improve, that the government might crack down on militant groups. In the meantime, he found a place to stay in the Bronx, and a job waiting tables at a restaurant in Brooklyn.

Then, in December, his father was murdered. After that, he knew he could never go home.

“Before going back to Bangladesh, I will kill myself,” he says, his voice calm and steady. “I don’t want to be killed in front of my family.”

There’s a rattling at the door. A key turns in the lock, and the door squeaks open. “Sorry,” says Rob Kerr, the Salvation Army’s local public relations secretary. He is a tall man, with a broad, gentle face and a formal manner.

“When you’re done, we need you to go upstairs,” he tells Subir and Shahadat. “There’s a list we’re getting everybody to sign, because not everybody’s where we think they are in the building. It’s on the second floor.”

Four weeks ago, that second-floor wing was empty. The Salvation Army planned to use it for another program in the fall. Then frightened people began staggering over the frigid border. And they just kept on coming.

Last month, Welcome Place asked if the Salvation Army could help house asylum-seekers. Sure, the shelter replied, they could fit about 30 people in the empty wing. No problem. After all, that’s what neighbours are for.

“At the time, we thought that would be more than enough,” Kerr says with a smile. “It would be plenty.”

So shelter workers scrounged a few couches off Kijiji and hung a flat-screen TV in the second-floor common area to create a lounge. They stocked the kitchen with pots and pans; small comforts to make 30 people feel at home.

Within a week, the rooms were full. Within two weeks, the number of refugee hopefuls staying there doubled. Last weekend, there were 84 asylum-seekers living in the Booth Centre. It does not have room for many more.

Cots are stashed in different corners of the building. On the fourth floor, beds for women; on the sixth and first, more for men. Couples with children stay at the Salvation Army family centre next door.

For much of the day, the second-floor wing is quiet. The asylum-seekers spend much of their days filling out paperwork, quietly resting on their cots or walking to Portage Place for coffee and a precious Wi-Fi connection.

Reporters from all over the globe have become a fixture in the building. At the moment, Kerr is rushing around attending to crews from Japan’s Nippon TV and CBC’s national news.

Kerr has suddenly been thrust into an international spotlight.

“It’s been an interesting thing,” he says. “I think a lot of us have said this, we’ve been very critical of the U.S. along the way. But we’ve been able to do that because we haven’t been involved.

“Now that we’re feeling that pressure, how do we respond?” he muses. “I hope we respond in a positive way.”

• • •

It’s an interconnected world, and almost nothing happens in isolation. Pressure from an event in one place cannot be contained by borders; it spills around mountains and across oceans. It sends human beings fleeing in search of places to breathe, to live, to be safe.

Many of the asylum-seekers do not know much about Canada. But they hope that it is that place.

“I know one thing,” Shahadat says. “In the world, everywhere, there is so much tension. But I don’t see anywhere in the newspaper that Canada has a terrorism attack, anything like that.”

A reporter starts to tell him about the mosque attack in Quebec last month, where a terrorist slaughtered six people at prayer. But the conversation moves quickly, and the moment slips away. At any rate, Shahadat feels safe.

In the quiet of the moment inside the Booth Centre, his thoughts drift back home.

“I’m worried about my family, my wife and my mother,” he says. “Still they are suffering. Especially my wife.”

Upstairs, the television in the second-floor lounge is tuned to CBC News Network; news is the programming of choice here, unless a soccer match is on. The screen flashes with a breaking headline: NEW U.S. TRAVEL BAN.

Suddenly, the air in the room feels thick and heavy. Conversations trail off in mid-sentence, and a dozen men watch the news in silence. For a few tense minutes, one man neglects the precious Canadian immigration paperwork he has been carefully working on.

It’s a surreal moment, considered in context. Outside this room’s spartan walls an international political storm is raging; a pitched battle over how nations ought to balance compassion and security, humanity and fear.

Here, in the eye of that storm, there are only thrifted couches and a handful of scared human beings.

They know what some politicians say about them, and some everyday people, too. They see it on the news. They know their future will be shaped by the judgments of distant people. People who will never know them.

Some who hate them.

•••

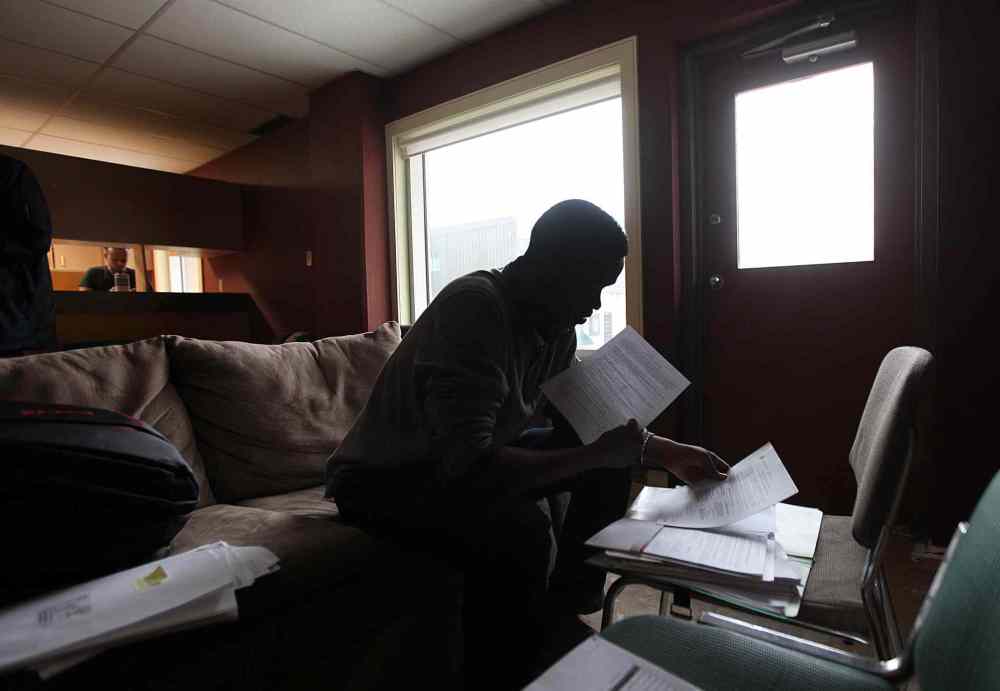

Maurice folds his lanky frame onto a bench at the Johnston Terminal, resting a thick folder of paperwork on his knee.

It was right after November’s election, Maurice says, when everything changed. He was in Atlanta on Jan. 20 when Donald Trump moved into the Oval Office, and a week later, when the president signed an order suspending all United States refugee claims.

Deportations and immigration raids surged. One by one, Maurice’s friends and fellow refugee hopefuls were seized by authorities in Georgia. Every night he lay awake, unable to sleep, fearing the clomping of boots at the door.

Yet when he thinks about the American president, his view is clear-eyed and sober.

“Donald Trump is an honest man,” Maurice says. “Before he came to power, he told them, ‘This is what I will do if you let me.’ So I believe that is what Americans want. He told them that is what he will do, and that is what he is doing.

“So I’m not against him. He is doing what he said he will do.”

And what Donald Trump did sent Maurice fleeing again, just like he once fled his home in West Africa. This time, he headed north towards Grand Forks, a corridor he’d learned about through a grapevine of people in the same situation.

Now he is here, hunched on a bench at The Forks. It’s been five days since Maurice climbed, frozen, into a Free Press vehicle at the end of a long night on Emerson’s main street. He just had his first meeting with immigration officials.

Until he fled West Africa, Maurice was a professional with a family; he has a university degree, and worked in a medical laboratory. He is Christian, and visited a Winnipeg church a couple of days ago. It wasn’t his denomination, but it didn’t matter.

“The body of Christ is not divided,” he says. “The body of Christ is the same everywhere.”

Religion is at the heart of his flight. Though Maurice doesn’t want to name his home country, he sketches its troubles: Islamic militants who “want everybody to be like them,” power struggles between sectarian groups, violence, fear.

“In Canada, you have the right to choose your religion, right?” he asks.

A reporter nods.

“You have the right to play the kind of music you want to play in your car, right? At your home, you have the right to play the kind of music you want to play, right?”

Again, yes.

“Well, in some countries, it’s not like that,” he says, shaking his head. “You don’t have the right even to play some music in your car. There are a lot of things, a lot of things…”

He trails off. Maurice repeats the phrase often — “there are a lot of things” — when the conversation grows too heavy for words.

For instance, “there are a lot of things” he felt when he got to the Salvation Army and spent his first night in a Canadian bed. He felt relaxed, happy — “joy in my heart” — for the first time in years.

“Now in Canada, I can sleep with my eyes closed,” he says. “In the States, I couldn’t sleep, I couldn’t eat, I couldn’t even go out. People are too scared to go out. The (Department of Homeland Security), the (Immigration and Customs Enforcement), they catch you. They catch people at bus stops.”

This relief does not come without pain. Maurice has a wife and two young children; they’re not in Canada. They decided to stay back at some point along the way after the escape from their West African home.

Maurice worries, blinking back tears. His dream is that his refugee claim will be approved, and one day they can join them here. He can get a job and begin to stitch their lives back together.

There is no way to know when, or if, that will happen. Under Canadian law, asylum-seekers may stay until their claim is processed. That could take months, especially now, as the system becomes more congested with the increasing number of people heading north.

In the meantime, there isn’t much to do. Maurice’s face lights up at the invitation to go for a drive around the city. He would like to see more of it, he says. And he would like to get to know Canadians, who do not know him.

“I want them to know that we are not criminals,” he says. “I had to leave for the safety of my family. We are not bad. We are only seeking for security. Anybody could be in our shoes, that’s what I want them to know.

“We are in Canada to make Canada great,” he adds. “All we need is security.”

It’s an echo of some words heard in other places, in much different ways.

•••

The world has become a very small place. Technology bridges gaps between people once made impassible by geography, but a little bit of luck and coincidence can do the same.

When Subir arrived at the Salvation Army, he started going through his list of contacts. He found a phone number for an old high school classmate he knew was planning to move to Canada. He called her.

“I’m in Manitoba,” he told her. “I’m in Winnipeg.”

She was delighted: she was in Winnipeg too, having moved here last year. She invited Subir and Shahadat to her home in West Broadway. They were able to use the Internet there, which was a relief. They contacted their families.

So now the two men are not so alone in this vast and unknown country they hope to call home. Bit by bit, they are starting to get more comfortable. There are a few differences they still have to adjust to, including the food.

At the Salvation Army, breakfasts are toast and jam, lunches feature macaroni or oatmeal. It’s not quite as, well… flavourful as Bangladesh’s succulent cuisine: “In my country, oatmeal looks like baby food,” Subir says, and laughs.

“But we’re enjoying it!” Shahadat adds quickly. Like most asylum-seekers here, they are eager to show gratitude.

There are other curiosities in this new land.

“I have a question,” Subir declares, gazing out a window.

“There’s a lot of ice out there. Why aren’t there a lot of accidents? In New York, if there was this much ice, everybody would be scared.”

Winnipeg’s renowned road conditions aside, their first few days have been comforting in many ways. “How are you doing?” strangers have asked. “You will be safe here,” a clerk at one store told them.

“The people are so gentle,” Shahadat says. “They’re always helping.”

Their introduction to Canada also included watching a period of a Winnipeg Jets game in the Booth Centre TV room.

“There’s a lot of dashing (Bangladesh for “pushing”),” Subir notes. “In field hockey, you cannot dash so much. But in ice hockey, it looks more like fighting.”

A couple of days ago they treated themselves to a meal at East India Company. They stuffed themselves.

“One plate is enough for two,” Subir says with another laugh. It’s a flicker of normalcy in a life a long way from normal.

“We are thinking, if we get all the papers, we’ll do a restaurant,” Subir says, and he grins.

When people are safe, when they can sleep at night, that is when dreams can begin.

•••

Shahadat and Subir come out of the cold again. Immediately, they feel warmth.

“Welcome home,” Ami Hassan says, shaking their hands.

Their breakfast is on the house, he tells them as they settle into seats at Falafal Place, his restaurant on Corydon Avenue.

“Do you want coffee? Tea?” Hassan asks, then takes matters into his own hands and orders his guests two glasses of freshly squeezed orange juice.

About that exuberant greeting?

“Because they deserve a home,” Hassan says with a shrug. “Everyone deserves a home.”

He should know. He emigrated to Canada from Israel 32 years ago, and his restaurant is a popular fixture on Corydon. Hand-made signs in the windows proclaim: “Management: Not like our neighbouring country, everyone is welcome here.”

Let’s just say Hassan is not a Trump fan and leave it at that.

Five days ago, they were shivering, exhausted and frightened in the lobby of the Maple Leaf Motel. Now they look well-rested. Upbeat.

Like Maurice, they’re not afraid to close their eyes now.

“I can sleep,” Shahadat says. “A relaxed sleep. In the U.S., I was quite nervous and afraid. Now I sleep all night.”

“Also feel hope,” Subir adds. “Maybe I will be with my family very soon. (But) when we can meet again, I’m not sure.”

When they reached their families a day earlier there were questions. A lot of questions.

What happens if their applications fail? (They have two chances to appeal.) Are all asylum-seekers given shelter? (Yes.) What do Canadians think about so many foreigners coming over the border? (Some like it, some don’t. Almost all are sympathetic.)

Subir spoke to his wife and two children; a son, 6, and his nine-year-old daughter, back in Dhaka. “(The children) were crying,” he says. “My son, he doesn’t go outside anymore. He always used to go out with his father, but now…”

His voice trails off. His eyes glisten with tears. He puts his arm around his best friend’s shoulder.

Yes, best friends. Even though they first met by accident in a New York City restaurant only two months ago — Shahadat the waiter, Subir the customer — they have forged a unique, unbreakable bond.

“In Bangladesh, it’s called ‘gigari dost,’” Shahadat says, spelling out the words with pen and paper. “Very best friend.”

And when did that friendship evolve?

“From the start of the bus in New York to the Salvation centre (in Winnipeg),” Subir replies.

Both men plan to live in Winnipeg if they’re allowed to remain in Canada and their families can join them.

Shahadat hopes to get more training as a fire-safety officer.

“I will start again to build my career,” he says.

Subir wants to find work in aircraft maintenance.

But now, like their perilous journey across the border, the future is shrouded in darkness. Nothing is guaranteed, except another night in a homeless shelter.

They find themselves in a land where it’s astonishingly cold, yet total strangers offer them warmth and free orange juice.

Lifelong friendships can be forged in a few intense days.

Finding a new home will take much longer yet.

randy.turner@freepress.mb.ca

melissa.martin@freepress.mb.ca

Randy Turner

Reporter

Randy Turner spent much of his journalistic career on the road. A lot of roads. Dirt roads, snow-packed roads, U.S. interstates and foreign highways. In other words, he got a lot of kilometres on the odometer, if you know what we mean.

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.