A ‘remarkable physician leader’

Anderson celebrated for her service to Indigenous people and other communities

Advertisement

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$1 per week for 24 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $4.00 plus GST every four weeks. After 24 weeks, price increases to the regular rate of $19.95 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.99/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19.95 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 18/04/2022 (1417 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

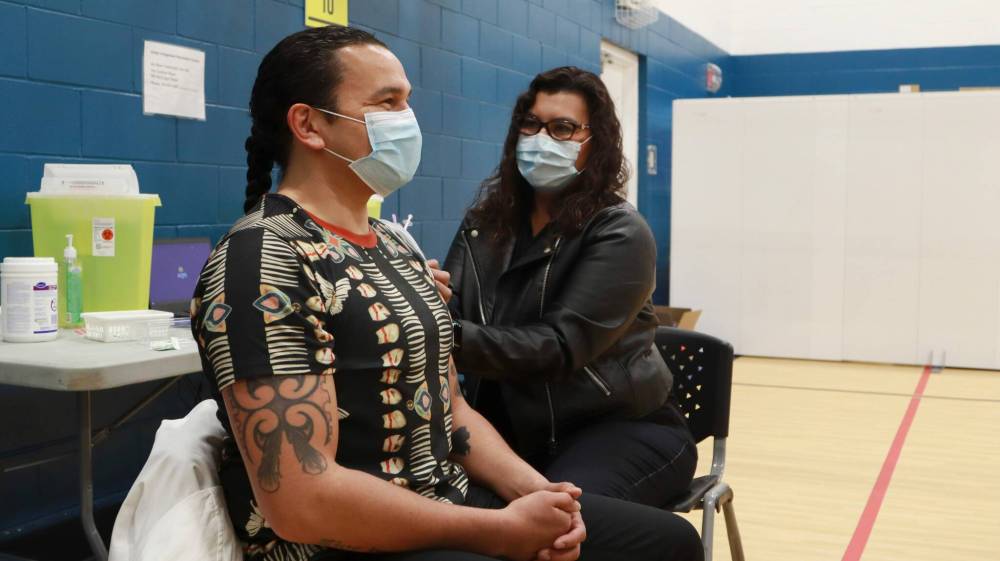

Dr. Marcia Anderson was thrust into the spotlight during the pandemic as a voice people across Manitoba would wait on to hear for guidance on fighting COVID-19 on First Nations, but she’s been devoted to serving her community for decades.

The public health lead of Manitoba’s First Nations pandemic response team has now been lauded as Doctors Manitoba physician of the year for 2022.

“I felt honoured even when one of my colleagues approached me and asked me if I’d be willing to be nominated for it,” Anderson, 44, told the Free Press.

“I think it’s important to me in terms of what it represents: which is the value of the work that I’ve been leading and part of, because that’s close to my heart, and the broader acceptance and seeing of the value in that work by my peers.”

Doctors Manitoba president Dr. Kristjan Thompson commended Anderson as a “remarkable physician leader.”

“Dr. Anderson is being celebrated for her critical work in supporting Manitobans from Black, Indigenous and racialized communities through the pandemic,” the physicians advocacy group leader said in an email to the Free Press.

“By ensuring the right data was collected, she was able to demonstrate the disproportionate impact COVID-19 was having on these communities in order to influence provincial policy and ensure earlier and targeted vaccine access. This work led to a reduction in the disparities in the subsequent wave of COVID-19, which is truly a major public health success story.”

Anderson always knew she wanted to be a doctor growing up in Winnipeg’s North End, but wasn’t always sure where she wanted to focus her work until she started medical school in 1998.

“We grew up pretty disconnected from First Nations community or culture, but, for me, in medical school was when that really changed,” she said. “I met some First Nations physicians, Indigenous physicians and other medical students.”

Through the mentorship of those physicians — she notes Dr. Barry Lavallee, who also received a medal of excellence from Doctors Manitoba this year, provided her support during her studies — she found the type of physician she wanted to be taking shape.

“Throughout medical school and residency, (I) observed and experienced a lot of racism,” she said. “It was those experiences that kind of further clarified, I wanted to work close to home.”

After her father had what she called “a really negative experience in health care,” Anderson was moved to, no matter where she went, return home and keep her work based around improving access to health care in her community.

After leaving for Saskatchewan for two years of her residency and Baltimore for a year to receive her master’s in public health, Anderson returned to Winnipeg and has been practicing with a focus on Indigenous health and equity, along with medical education, since 2007.

“Those kind of theoretical foundations, those relationships, the community connections that I have, and have built… all of that is what really laid the foundation for the work in the pandemic that I did,” she said.

Anderson wears many hats outside of the COVID-19 group. Three days a week, she works in public health. She sees patients at Grace Hospital in the adult medicine clinic as a general internist with a cardiology focus practice on Wednesday mornings. The rest of the time, she serves as the vice-dean for Indigenous health, social justice, and anti-racism at the University of Manitoba.

Mulling on the H1N1 influenza pandemic in 2009, Anderson recalls “significant missteps” from the federal government’s response that harmed Indigenous communities, already disproportionately impacted by the illness.

“People might remember the body bags being sent to communities instead of other health supplies or the refusal to send alcohol-based hand sanitizers because the then-minister said something about how people might drink it,” she said. “So when we knew COVID-19 was coming, I think there were lots of First Nations health experts who didn’t want that to be the experience of their stories again this time.”

The executive director of Ongomiizwin Health Services and head of the Indigenous Institute of Health and Healing at the U of M, Melanie MacKinnon, suggested putting together what would become the Manitoba First Nations Pandemic Response Co-ordination Team, with Anderson as the public face.

The work was collaborative with different partner organizations, including the Assembly of Manitoba Chiefs — and that collaboration and support was its strength.

“The big opportunity of COVID-19 at that time was, we were all scared, right?” Anderson said. “And because of what was about to come, there was a lot more openness for creative responses and understanding that we don’t have to be stuck in the status quo ways we’ve done things in the past, because that’s not going t o work here.”

The goal wasn’t to eliminate the structural gaps that cause disproportionate harm to Indigenous people in Manitoba, Anderson said, but to minimize that gap to improve accessibility to health-care tools and knowledge.

What resulted was “probably more First Nations-led influence and direct service delivery, throughout this pandemic, as far as the health-care response goes, than we have had probably ever in the past and the health-care system.”

Moving forward, the goal will be to look at the task force successes and use them to inform broader policy.

“I think, at least I hope right now, because the province is still in a period of health-care transformation and trying to pick up some of that work that was being done pre-pandemic, and discontinued through, hopefully, that will be a bit smoother and easier to facilitate than it has been in past years,” Anderson said.

She’s now able to look back on the past two or so years tinged with uncertainty and fear, along with hindsight. When she’s not leading an entire pandemic response team, Anderson said she’s spending as much time outside as possible reading, working out and spending time with her two kids.

“I would say it’s been up and down over the past couple of years,” she said.

“There have definitely been times when I felt much more burned out. I wouldn’t say I feel like that right now… but it has been, and I think for many health-care providers and me included, the toughest two-plus year period of my career or of my life.”

malak.abas@freepress.mb.ca

Malak Abas is a city reporter at the Free Press. Born and raised in Winnipeg’s North End, she led the campus paper at the University of Manitoba before joining the Free Press in 2020. Read more about Malak.

Every piece of reporting Malak produces is reviewed by an editing team before it is posted online or published in print — part of the Free Press‘s tradition, since 1872, of producing reliable independent journalism. Read more about Free Press’s history and mandate, and learn how our newsroom operates.

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.

History

Updated on Monday, April 18, 2022 10:20 AM CDT: Corrects reference to the "federal government's response" regarding H1N1