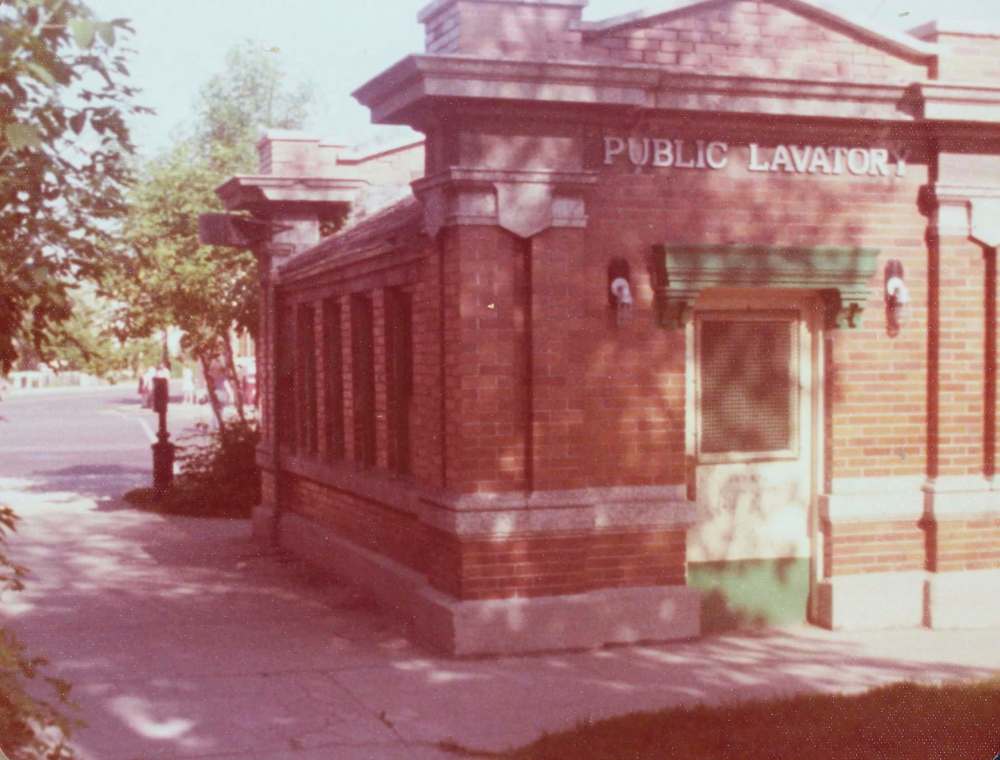

Comfort zones

Long-gone, city-run washroom facilities were frequently used

Advertisement

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$1 per week for 24 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $4.00 plus GST every four weeks. After 24 weeks, price increases to the regular rate of $19.95 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.99/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19.95 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 11/12/2016 (3376 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

Today, civic-infrastructure debates usually involve things such as roads, bridges, pools and libraries, but at one point in the city’s history, public washrooms — or “comfort stations,” as they came to be known — were a hot-button item.

In December 1887, a citizen by the name of Richard Harris summed up the position of many at the time in a letter to the Manitoba Free Press.

“I have been in many large cities and towns and was always able to find places of this kind pretty easily, but in Winnipeg I have not been able to find any, except… one at the (train) depot which the CPR have the usual monopoly by keeping same very secure under lock and key,” he wrote.

It is a shame to think that when the city acts in the interest of the public… some people will have imaginary injustices which, when investigated, prove to be nothing less than selfish financial interests — Mayor Thomas Deacon on opposition to public washrooms

Despite the calls for public washrooms, they were near the bottom of a long list of infrastructure needs in a booming Prairie town.

Finally, in 1905, the city built a prototype on Market Avenue between city hall and the Market Building. It was a busy location during the workday and on evenings and during special events on weekends. An underground public washroom accessible from the street level took the pressure off city officials to have to open these buildings after-hours.

Fraught with delays, the station took two years to complete, and when it was done, the anticipated rollout to the city at large never happened.

In the years that followed, the demands for public washrooms grew louder.

Women complained that while men could rely on saloons to do their business, they were barred from such places. Others, especially those associated with the temperance movement, blamed that reliance on saloons as a contributing factor to the heavy rate of alcohol consumption in the city. The provincial health board passed a motion calling on the city to install them.

Public washrooms needed a political champion, someone who could both secure funds and get the support of the various city departments needed to approve the work that needed to be done above and below the ground. They found one in civil engineer and mayor Thomas Deacon.

Just days after being sworn into office in January 1913, Deacon appeared before the board of control, the committee in charge of the city’s purse strings, to say: “It is a scandal to Winnipeg that no public conveniences of this kind have been introduced. I’ve heard a great deal of adverse comments from visitors about our backwardness in this respect.”

The board agreed to fund the stations if Deacon put a plan together.

That summer, architect William Bruce was set to visit England on behalf of a consortium of local construction companies to study the latest large-scale construction projects there. Before he left, Deacon asked him to also check out their comfort stations.

Upon Bruce’s return, the two men put together a plan for what they hoped would be at least three public washrooms along Main Street.

The comfort stations would consist of an ornate building at street level that would house a men’s entrance on one side and a women’s entrance on the other. Under the street would be the respective washrooms, with six stalls each. The mechanical area would separate the two rooms.

In the December 1913 civic election, voters weighed in on the “bylaw to create a debt of $50,000 for the purpose of providing the cost of providing and maintaining public lavatories, urinals, water closets and like conveniences in the city of Winnipeg.” It passed by a vote of 4,900 to 1,300.

The $50,000 was enough to complete the final design work and construct just one comfort station, so Deacon and Bruce started with Portage and Main. They soon found the intersection was a very crowded place, both above and below ground. Finding the space required was too difficult, so they looked to alternate sites.

In the end, it was agreed it would be best if they split the comfort station into separate sites for men and women. They chose Fort Street just south of Portage Avenue for the men, and women got Garry Street just south of Portage.

The choice of location was not without controversy. Surrounding businesses, especially the financial institutions along Fort Street, protested by a petition and letter-writing campaign that included many of the city’s most powerful businessmen who sat on their boards. Deacon reacted angrily, stating: “It is a shame to think that when the city acts in the interest of the public… some people will have imaginary injustices which, when investigated, prove to be nothing less than selfish financial interests.”

With little fanfare, the men’s comfort station on Fort Street went into service Nov. 23, 1914, and the women’s Nov. 26.

The stations were open from 6 a.m. to midnight Monday to Saturday and from noon to 10 p.m. Sunday. Over the decades, the Monday-to-Saturday hours were whittled down to 8:30 a.m. to 10:30 p.m.

To ensure they remained clean, that the boilers kept working in the winter and vagrants were sent on their way, attendants were hired. There were two for each station.

The comfort stations were a hit with the public, and in the spring of 1916, the board of control gave the funds for two more, on Logan Avenue east of Main Street and Selkirk Avenue east of Main. These stations, which combined men’s and women’s rooms, opened in early 1917.

By the late 1940s, the Fort and Garry stations found themselves under threat from traffic. As the city’s suburbs grew, more and more vehicles passed through the downtown on their way to and from them. The station entrances took up a valuable traffic lane the city’s engineering department wanted back.

Councillors would not agree to close them because, despite their age and deteriorating condition, they were still popular amenities. A survey in 1948 showed a weekly average of 5,844 men and 1,064 women used them.

A compromise was reached. The Garry Street station would be closed and demolished. The Fort Street station would be re-excavated twice as large so it could accommodate both men and women. The entrance would be through a single staircase on the sidewalk mirroring the entrance to a New York City subway station.

On April 17, 1950, the new, $50,000 joint comfort station was unveiled under the watchful eye of Alderman James Black, its strongest proponent.

The city’s other comfort stations did not get a second chance. The Market Avenue station was demolished along with the old city hall in 1962.

The Logan Avenue station was also a victim of traffic when, in 1966, the Metropolitan Corporation of Greater Winnipeg announced a $1.3-million road works project to improve approaches to the Disraeli Freeway. The lane occupied by the Logan station was in its sights.

A couple of surveys in the 1960s showed around 8,000 men and 1,000 women used the Logan facility weekly, so the city initially deemed it “essential” and refused to close it. Eventually, Metro got its way in 1971. The city’s vow to rebuild one in the area faded when officials realized it might cost up to $100,000 per year to operate it.

Selkirk Avenue’s station faded away with little fuss. It was the least-used comfort station, and its hours were cut back over time to save money on the salaries of attendants. It closed a couple of years after the Logan station.

The rebuilt Fort Street station saw a steady decline in traffic through the 1970s, down to about 1,000 men and 400 women per week. The city calculated that when operating costs were factored in, it was costing 76 cents per visit for men and more than $2 for women. It was closed as a cost-saving measure April 30, 1979 and demolished a few years later.

The public washroom located on Broadway at Osborne Street from 1973 to 2006 wasn’t a city facility. It was constructed and operated by the provincial government to serve the small provincial park across the street from the legislature.

The debate over the provision of public washrooms reappears from time to time — most recently in 2008, when architect Wins Bridgman had two outhouses placed at the intersection of Higgins Avenue and Main Street in an attempt to control the number of people using area lanes and properties as toilets.

The city had them removed and agreed to study the options available for offering public washrooms in “strategic” locations. Eight years later, that report has yet to be completed.

Winnipeg could use another political champion such as Thomas Deacon.

Christian writes about local history on his blog, West End Dumplings.

History

Updated on Sunday, December 11, 2016 11:03 AM CST: Formatting

Updated on Tuesday, December 13, 2016 3:32 PM CST: Corrects location of Selkirk Avenue station.