A soldier shunned

By: Randy Turner

Posted:

Last Modified: | Updates

By: Randy Turner

Posted:

Last Modified: | Updates

Advertisement

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 09/11/2013 (4422 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

WINKLER — The last soldier has remnants of the war spread out on the kitchen table.

There is the grainy black-and-white photo of his troop, circa 1943, the Princess Patricia Canadian Light Infantry.

“The way we decided it was that Canada deserved fighting for.”

-Peter Engbrecht

Which one is you, someone asked.

“I’m that old-looking boy right there,” Harvey Friesen says.

That boy was just 16 years old when the photo was taken, fresh off a train from his home in Winkler. He took the trip with a schoolmate, and both teenagers were looking for adventure.

Friesen then shows the letter of commendation for his training stint at Suffield, Alta., where he and fellow recruits took part in mustard gas experiments, which put him in a hospital bed for eight days, covered head-to-toe in blisters. It would be the closest the teenager would get to live action.

Finally, Friesen shows his navy Legion blazer, which contains his volunteer, victory and Queen’s Jubilee medals, and a gold bar signifying a commendation from the Minister of Veterans Affairs in 2006.

“They’re all on the right side,” Friesen said, brushing the medals with his fingers, “like the poppy, over the heart. Of course, the guys who went overseas have many more medals. And they earned them.”

But this isn’t a story about medals. It’s about the little known experiences of young Mennonite men who, in many cases, defied their own family and church to enlist and fight in Second World War. In all, it’s estimated that between 3,000 and 4,500 Mennonites volunteered for the Armed Forces. In some rural Manitoba communities, that decision earned them only scorn.

And if these soldiers did survive, they did not return to a hero’s welcome. Many were shunned and ostracized by their churches. Even their family members.

Figuratively damned if they didn’t, and literally damned if they did. Some brothers left for the war, some stayed. Some families were torn apart.

“It was a cultural dilemma and a moral dilemma,” noted Royden Loewen, chair of Mennonite Studies at the University of Winnipeg. “There was all kinds of dilemmas.”

And to this day, some of those wounds that never involved a battle field have not yet healed. And only a precious few of the soldiers are left to tell the tale. Now 87, Friesen is the only remaining Second World War veteran alive in Winkler.

So he shrugs.

“I don’t know how much interest there will be in this story,” he said. “I’m the last one left.”

Thou Shalt Not Kill

A pillar of Mennonite faith is pacifism. Thou Shalt Not Kill. The church maxim for centuries has been: “Where hate fails, love conquers.”

After all, most Mennonite immigrants who had settled in Manitoba had fled their old homeland in Russia for that very reason, and when they first arrived in the 1870s (a second wave came in the 1920s) they were granted exemption from military service by the Canadian government.

It’s not as though Mennonites hadn’t fought before in the name of self-preservation. They had taken up arms in Russia and Germany in two recorded instances over five centuries. But in Canada, the Second World War marked the largest involvement of Mennonites in military conflict, a phenomenon that transpired for several reasons.

In communities where the church was less evangelical, for instance, enlistment was never endorsed, but not strictly forbidden. Some young Mennonite men, like many recruits at the end of the Depression, were just seeking adventure. For others already veering away from the church, joining the forces was a means of assimilating into the mainstream of Canadian society. Said Loewen: “Now you’ve earned the right to full assimilation. I think some of them came back feeling a sense of liberation.”

Despite the fact that all eligible Mennonites could have applied to be conscientious objectors — most serving in work camps on Canadian soil — men from across Manitoba signed up for duty.

“There was a lot of feeling of loyalty to serve your country,” Friesen recalled. “I was very proud. And that’s how a lot of young fellows felt.”

In Steinbach and district alone, records show 117 men and women served in the Canadian Armed Forces — including six boys from one family overseas at once (Barkman) and five from another family in active service (Reimer). In Winkler, 108 of 126 men and women enlisted had common Mennonite names, according to the book Mennonites at War, written by Peter Lorenz Neufeld.

Another factor in the shift away from pacifism was undoubtedly the shadow of the First World War, where Mennonites were steadfast in keeping out of the conflict, as was their right under their settlement agreement with the federal government.

As noted in Neufeld’s book, Dr. C.W. Wiebe, of Winkler, said: “During the last war our young men were allowed to remain home and take advantage of good crops and high prices, and our English neighbors saw this. We Mennonites like to emphasize the sacrifices we make, when really we make no sacrifices.”

Added Elder Toews: “When the (non-Mennonite) soldiers returned after the war, we were told that many a widow’s son had fallen during that long struggle. Where were our young people? Many were found in the dance halls where the returned boys met them and felt this deeply.”

That underlying resentment festered for decades in many rural communities.

“That’s a pretty sore point if you’re sending your boys overseas… and the Mennonite farmers are buying up land,” Loewen says. “There were hard feelings.”

Hence the tension not just between Mennonites and their neighbours, but the uncertainty among Mennonite leaders themselves in establishing a clear message to their congregations during the early years of the war.

The collision of culture, religion and an evolving Mennonite community led to such unique situations as that of brothers John and Ted Friesen of Altona. John, the eldest son, had left Altona to teach in Virden a few years prior to the war, decided to enlist at age 30.

Although John has passed away, the brother’s story was captured in the National Film Board presentation, The Pacifist Who Went to War, released in 2002. (Watch the movie at the end of this article.)

“When I saw some of my students go off to war, then began reading the lists of missing boys and girls who I had taught, I became to examine my own conscience,” John said, in the film, of his decision to enlist in the Air Force. “I had let the family tradition down. It was accepted, but reluctantly.”

Brother Ted, now 93, was a conscientious objector. The Friesens’ father, D.W. Friesen, was the Mennonite church deacon and respected businessman.

In an interview with the Free Press, Ted Friesen said his father was “was very sorry, very, very much” about his eldest son’s decision to go to war. Yet the family held together.

”Relations were always good,” Ted notes. “That may seem strange, but it’s a fact.”

General silence

So it was that hundreds of young Mennonite men — farmers, teachers, businessmen, teenagers — broke ranks with their religious upbringing to join the ranks of the Canadian Armed Forces. Some, like 16-year-old Harvey Friesen, would never set foot overseas. Others did and never returned.

Many would experience the same horrors and say the same prayers as their fellow soldiers, regardless of faith. And some would earn the highest medals that could be earned in battle.

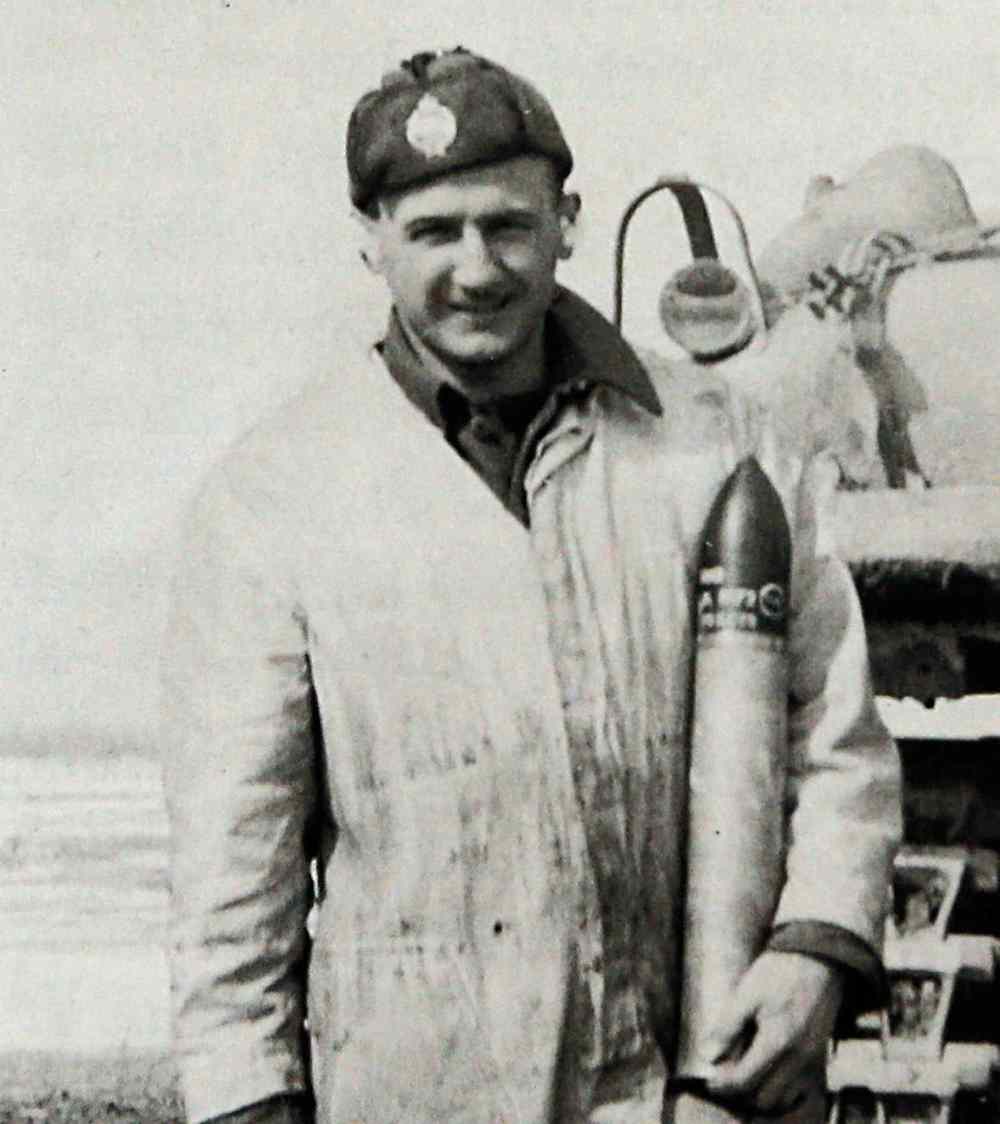

Such is the story of Peter Engbrecht of Boissevain, a small farming community in southwestern Manitoba, who as a young man was considered a larger-than-life figure at home. Engbrecht was one of 15 Mennonites from Boissevain to enlist, joining the Royal Canadian Air Force as a bomber gunner.

In a British Wings magazine article, later reprinted in the Boissevain Recorder, Engbrecht described his eagerness to join the war effort, despite objections from the local church authorities.

“A family council was held,” he said. “We finally consulted the bishop. My father couldn’t refuse me permission to go since he had himself fought for seven years in the Russian army and during the Revolution. The way we decided it was that Canada deserved fighting for.”

By 1944, Engbrecht was a household name in Canada, becoming the RCAF’s only ace who was not a pilot. He shot down eight fighters and disabled a ninth, on bombing runs over Belgium, France and Germany.

Engbrecht was decorated for bravery by King George himself, and the subject of a parade on Parliament Hill. His exploits were trumpeted in newspapers across the country, and not without mention of his conflicting circumstance. Noted the Toronto Star: “The paradoxical Peter Engbrecht is, all at once, a member of a religious sect which forbids participation in wars, of pure German descent, a member of the RCAF.”

Yet Engbrecht wasn’t so openly revered in his own Mennonite community back home. He had a tendency to regale the locals with his war stories and brazenly wore his uniform to church, sitting in the third row.

“Some loved his stories; many did not,” Engbrecht’s cousin, Rudi, wrote in an email to the Free Press. “Others who had returned from the war, including Anglo-Saxons and other Mennonites, appreciated that he had enlisted and fought, but remained quiet, often resentful, that he talked with such pride and in such detail about personal exploits.

“This general silence in the community was also the silence of the Whitewater Mennonite Church he attended. He attended proudly in his RCAF uniform but he was met with silence. The Church did not know how to respond.”

Rudi Engbrecht adored his uncle, who passed away in 1991 at age 68. But while the RCAF ace might have been seen as too prideful by other locals upon his return, few if any Mennonites were welcomed home with universal acceptance.

Worse, many weren’t accepted at all.

"He could never apologize"

When the Second World War called, more than 100 young men from Altona answered. At the time, in the early 1940s, the southern Manitoba hamlet was almost exclusively a community of evangelical Mennonites, where the first language on the streets was low German.

And to understand the reception that awaited those men upon returning to their town is to know that the Altona United Church exists. Because Altona United was founded by Second World War veterans of Mennonite descent.

Why? Because those returning soldiers were given two choices: Publicly apologize for joining the war effort or have their names taken off the Mennonite church register.

Altona United held its first service in a school basement on Easter Sunday in 1953. It was attended by Anne Braun, whose husband Peter served in Belgium. The couple, who were childhood sweethearts, married immediately after the soldier’s return in 1945.

But Peter Braun refused to confess to his Mennonite congregation.

“He felt it was his duty,” said Anne, sitting in the pews of Altona United. “My husband said he could never apologize for protecting his own country.”

Sitting in the pews with Braun, now a widow, is Doris Hildebrand, whose late husband Peter also served in a tank unit overseas. They are joined by Dorothy Braun, whose late father-in-law, Art Braun, was one of the United Church’s founding members.

Even more than 60 years later, the subject of their loved ones being spurred by their family and church is fraught with emotion.

“I think he (Peter Braun) felt more from his own family than the community,” Anne says, of the cold reception. “His sisters were very evangelical.”

Then Anne pauses and stares off. What is she thinking?

“It brings back a lot of memories,” she replied. “A lot of worry.”

Adds Dorothy: “It’s the clash of new times and old times. You have people who weren’t prepared to follow the rules. It was a big upheaval in the community.”

A soldier’s worst nightmare

Dorothy Braun doesn’t recall her father-in-law showing anger towards his Mennonite brethren. His response was, in her words, “Okay, you don’t want us? We’ll figure this out.”

So Altona United was born. In fact, a large percentage of Mennonite soldiers never did return to their parents’ church.

“It is no wonder that most who came home turned to denominations other than Mennonite,” Neufeld wrote in Mennonites at War.

“Many soldiers turned to non-Mennonite sweethearts and wives. For them, not only was there now a loving companion with non-pacifist views giving moral support, but also often a ready-made, non-Mennonite church congregation which did not condemn them.

“As a youngster, I witnessed the pain and anguish in my parents’ generation when about a dozen Mennonites enlisted, and one skyrocketed to international fame as a war hero (Engbrecht)… Hundreds were killed in action. After the war, many of those who returned faced strong rejection in their congregations and left. My heart still bleeds for those men and their families.”

Mel Reimer, who attended high school in Altona and later became president of Morden Legion, was a boy during the war years. But he knew well the emotional collateral damage endured by veterans of Mennonite stock.

“I remember very clearly… they all had very sad stories to tell,” says Reimer, now in his mid 70s. “Not only war, but their return. You were largely not welcomed by the community. They were associated with being murderers and killers. Bad people. Whether they had actually killed or shot anybody didn’t matter.

“People would walk on the other side of the street. They talked about you when you could hear them. Very unfortunate. A lot of these guys suffered severely. They didn’t say, ‘Thank you for our freedom’. They were shunned.”

Adds Royden Loewen: “This is a soldier’s worst nightmare. You sacrifice and you come home and there is no soldier’s welcome. I think coming home, in some ways, was more difficult. You realize you’re persona non grata.”

Not a comfortable pew

Again, the reception for Mennonite soldiers, just like their departure, was not a uniform experience. In Steinbach, a community dinner was held in the returning soldiers’ honour. Each veteran was given a leather wallet to mark the occasion.

There was no dinner in Altona. Instead, Mennonite war veterans who didn’t apologize founded their new church, which served as a lingering source of contention for decades.

“We were like also-rans,” Anne Braun notes.

But in those roots was forged a conviction that remains as strong for the widows as it was for their now departed soldiers.

“You really had to know what you believed in,” Dorothy Braun says. “You had to want to belong here. It was not a comfortable pew.”

Yet pain still lingers. Doris Hildebrand tells a story about how her husband Peter’s tank was hit and one of his crew members was killed. As sometimes happened in the confusion of war, Peter’s parents in Altona soon received a notice that their son was missing in action and presumed dead. No family members came to console her.

“My mother (in-law) sat in a rocking chair and rocked and rocked,” Hildebrand recalls, a memory that still evokes tears. “Her hair turned white in a month. Nobody came. That was the saddest thing.”

But Peter did return alive, and later married Doris in 1953, the same year of the inaugural service of Altona United. Yet for years, Peter Braun often awoke in the middle of the night with a recurring nightmare.

It was the day he landed on Juno Beach, during the Battle of Normandy. Canadian soldiers were being mowed down by German artillery, so the tanks that followed had no choice but to push ahead, even if it meant running over his fallen countrymen. Said Hildebrand: “It was a movie that never changed (in his mind).”

The horrors of war. The conflicts of faith. Such was the unique burden of many Mennonite soldiers. So while time has almost completely depleted their ranks, their story remains indelible to those who still remember.

“I wouldn’t say forgotten, but not talked about,” Doris Hildebrand says. “Because some things you don’t forget.”

"We’re all brothers in the end"

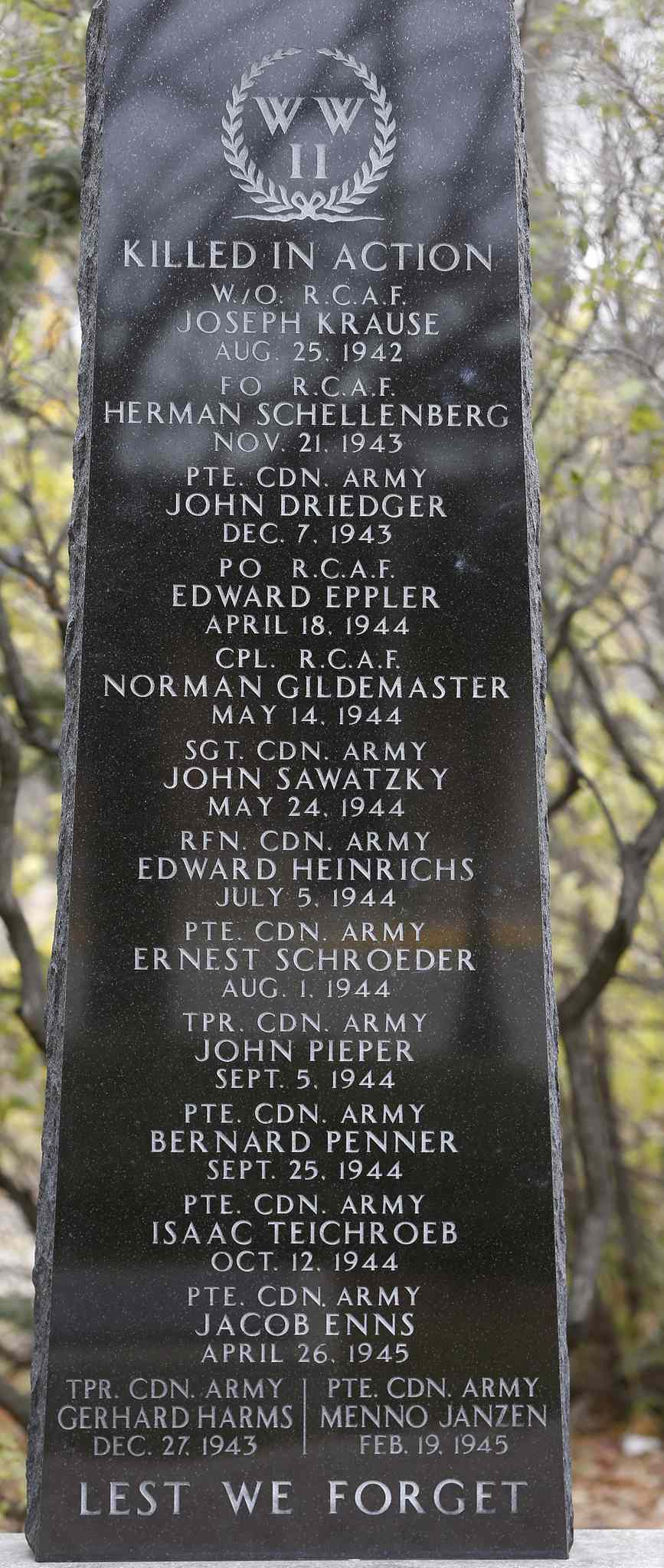

It took over 50 years to erect a cenotaph for fallen Second World War veterans in Winkler. Across the park stands a memorial for conscientious objectors.

Two solitudes still separated but equally remembered.

Harvey Friesen said efforts to have a cenotaph built were for years repeatedly “brushed off” by town fathers. “I think they weren’t interested in glorifying the war,” he reasons.

But as time passed, objections waned.

“It should have been done many years ago,” Friesen notes. “The longer it wasn’t there, the more people said, ‘Why don’t we have a cenotaph? Those people who lost their lives should be properly remembered.”

There is a cenotaph in Altona now, too, built in 1995. And the congregation of Altona United still holds a Remembrance Day service, as it has since 1953.

When asked if he ever would have apologized for running off to war at age 16, Friesen instantly replies: “No. I was proud to defend our country. Under the circumstances, I’d do the same thing again.”

But Friesen has no lingering animosity for the hard choices war forced on young men many years ago.

The soldiers, he reasons, have been buried. The conflicts of conscience past should be, too.

“Time to move on,” the last soldier says. “We’re all brothers in the end.”

randy.turner@freepress.mb.ca

Twitter: @randyturner15

Next page: Watch The Pacifist Who Went To War

The Pacifist Who Went To War

ONFB, 2002, 51 min 59 seconds

This documentary is the story of two Mennonite brothers from Manitoba who were forced to make a decision in 1939, as Canada joined World War II. In the face of 400 years of pacifist tradition, should they now go to war?

Ted became a conscientious objector while his brother went into military service. Fifty years later, the town of Winkler dedicates its first war memorial and John begins to share his war experiences with Ted.

The Pacifist Who Went to War by ONFB , National Film Board of Canada

Randy Turner

Reporter

Randy Turner spent much of his journalistic career on the road. A lot of roads. Dirt roads, snow-packed roads, U.S. interstates and foreign highways. In other words, he got a lot of kilometres on the odometer, if you know what we mean.

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.

History

Updated on Saturday, November 9, 2013 9:26 PM CST: Corrects typo.