School ventilation upgrades years from finish line

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$1 per week for 24 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $4.00 plus GST every four weeks. After 24 weeks, price increases to the regular rate of $19.95 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.99/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19.95 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 09/01/2023 (1153 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

The COVID-19 pandemic will all but certainly be over by the time highly-anticipated ventilation assessments and upgrades to limit infectious disease transmission in Manitoba public schools are complete.

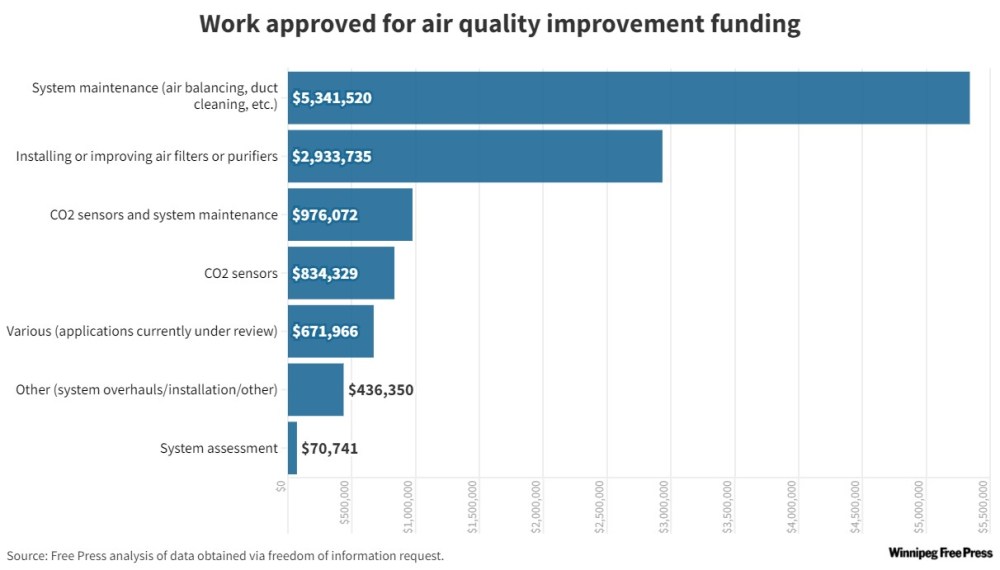

A total of $11.3 million, a combination of provincial and federal dollars, was earmarked to improve air quality in K-12 buildings during the ongoing global health crisis.

The Winnipeg School Division, the largest in the province, was allocated approximately $2.5 million — about $85 per student — for projects scheduled in 78 facilities, according to a breakdown of grant distribution.

MIKAELA MACKENZIE / WINNIPEG FREE PRESS

The school division has already purchased standalone air filters for portable classrooms and used ventilation-specific dollars to update central systems with new MERV 13 air filters, where possible, and CO2 sensors.

“Testing, adjusting and balancing (TAB) contract work is underway and is expected to take at least another two years to complete and be analyzed for optimization,” division buildings director Mile Rendulic said in a statement.

To date, maintenance teams have been allowing heating, ventilation, and air conditioning (HVAC) units to run continuously throughout the school day so air exchange is maximized, Rendulic said.

The school division has already purchased standalone air filters for portable classrooms and used ventilation-specific dollars to update central systems with new MERV 13 air filters, where possible, and CO2 sensors.

The Pembina Trails School Division has purchased upwards of 150 CO2 sensors to its buildings’ central HVAC systems to date. These sensors monitor return airflow from all classrooms and adjust fresh air intake accordingly.

These devices were “the most sustainable solution” to bettering air quality, given the capital city division’s existing infrastructure, per its facilities and operations department.

In Seven Oaks, superintendent Brian O’Leary said priority has been placed on ensuring maximum airflow in each respective building and commissioning older HVAC systems; he likened the latter to the equivalent of a mechanic tune-up to ensure a vehicle is running smoothly.

“The things that can be done quickly are limited to cleaning coils, recommissioning, some duct work, but it takes a while to do whole systems,” O’Leary said, adding ventilation challenges are generally in older buildings and K-12 facilities built as open-area schools.

Public and independent schools have used grants to replace aging windows with new ones that open, upgrade bathroom fans, retrofit air handling units, buy control valves, and undertake duct cleaning — a general maintenance service not recommended for infectious disease control.

The most modern and advanced HVAC systems are still not good enough to 100 per cent protect a building’s occupants from airborne diseases, said Amy Li, assistant professor of civil and environmental engineering at the University of Waterloo.

The Ontario researcher, who studies indoor air quality and filtration devices, is a vocal proponent for a multi-layered approach — with mandatory masks as a starting point — when it comes to reducing the risk of COVID-19 transmission indoors.

“There is a hierarchy of approaches to improve indoor air quality: the first one would be source removal, the second one is ventilation, and then after that, it is air cleaning,” she said.

Li said following proper HVAC maintenance is critical and can be complemented with portable air filters effective at removing particulate matter from the air, although she indicated frequent monitoring is necessary to know when to swap out dirty filters.

RUTH BONNEVILLE / WINNIPEG FREE PRESS FILES

In Seven Oaks, superintendent Brian O’Leary said priority has been placed on ensuring maximum airflow in each respective building and commissioning older HVAC systems.

One University of Toronto academic said his school-age daughter informed him a machine running a HEPA filter placed in her classroom early on in the pandemic was unplugged soon after it arrived because “it was too loud.”

As far as civil engineering Prof. Jeffrey Siegel is concerned, there is one extremely underrated, low-cost way to improve air quality: educating occupants on risk and response.

Siegel said school staff should be equipped with knowledge to make informed decisions to protect their communities during high-risk activities — be it by opening windows, promoting temporary mask-wearing, moving outdoors or cranking up a HEPA filter, among other options.

If a classroom has a CO2 sensor, the ability to observe readings over time can prove useful to identify riskier periods, he said.

“Schools, in particular, are very strapped for cash and as parents, we don’t tend to care about the HVAC system in our kids’ schools — but we really should,” Siegel said, adding emerging research shows there is reduced transmission of viruses in classrooms when ventilation and filtration is improved.

Not only does improved overall air quality reduce the COVID-19 risks, he noted, but it can also address concerns about asthma, allergies and respiratory illnesses overall — and ultimately, result in higher attendance and academic performance.

MIKAELA MACKENZIE / WINNIPEG FREE PRESS

HEPA filter units in portable classrooms at Sisler High School in Winnipeg.

maggie.macintosh@freepress.mb.ca

Twitter: @macintoshmaggie

Maggie Macintosh

Education reporter

Maggie Macintosh reports on education for the Free Press. Originally from Hamilton, Ont., she first reported for the Free Press in 2017. Read more about Maggie.

Funding for the Free Press education reporter comes from the Government of Canada through the Local Journalism Initiative.

Every piece of reporting Maggie produces is reviewed by an editing team before it is posted online or published in print — part of the Free Press‘s tradition, since 1872, of producing reliable independent journalism. Read more about Free Press’s history and mandate, and learn how our newsroom operates.

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.