Faces of the pandemic A look at lives of four Manitobans lost to COVID-19 over past 12 months

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$1 per week for 24 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $4.00 plus GST every four weeks. After 24 weeks, price increases to the regular rate of $19.95 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.99/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19.95 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 11/03/2022 (1457 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

They are people, not statistics.

Clarke Gehman, Bernice Oleschuk, Luigi D’Abramo and Mary Cartlidge had family who loved them. They had more years ahead of them, but were taken too soon. They contracted COVID-19, and died because of it.

Manitoba is on the cusp of a grim anniversary.

March 12 marks the second anniversary of the first positive case of COVID-19 being detected in Manitoba. March 27 marks the second anniversary of the first death of a Manitoban from the disease caused by the novel coronavirus.

Her name was Margaret Sader.

Like most of the victims of COVID-19, we know little about Sader. She was a woman in her 60s who worked at a dental supplies clinic. Almost two years after Sader’s death, a family member said they didn’t want to comment for this story.

Last year, the Free Press marked the first anniversary of the detection of the virus in the province by looking at the lives of people lost to the pandemic. At the time, 911 Manitobans had fallen victim to COVID-19, most during the second wave from October 2020 to January 2021.

In the second year, nearly 800 people more joined them.

That’s 1,710 Manitobans whose lives were cut short. (Manitoba’s 123 deaths per 100,000 people is the second-highest per capita rate in the country, behind only Quebec, at 164.).

Here are four lives we lost in the last year.

We know how they died, but this is how they lived.

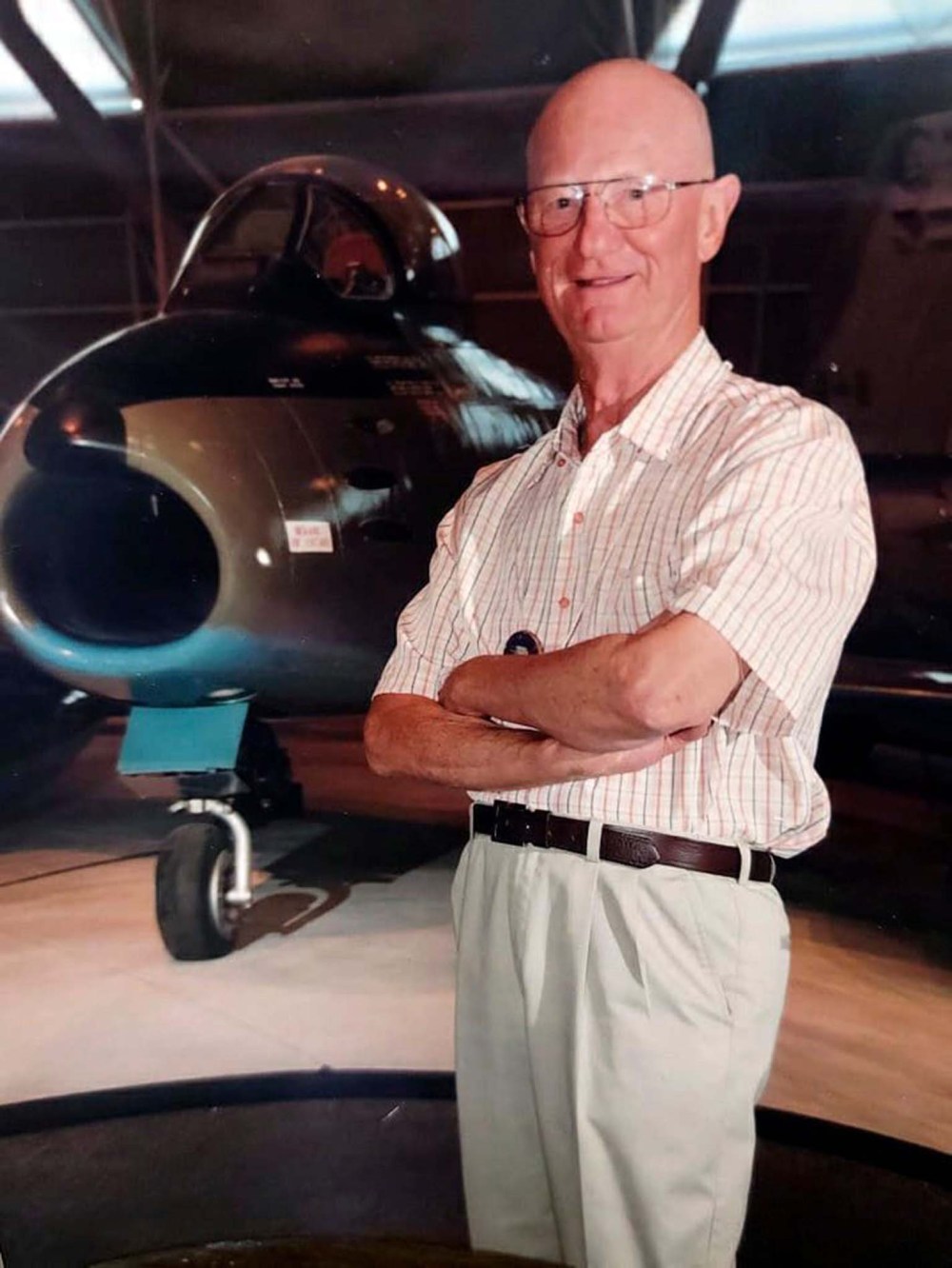

Clarke Gehman

Clarke Gehman wanted to be a photographer, but the military had other plans for him.

Gehman, who died Feb. 11, at 84, flew fighter planes in Canada and Europe, and was part of International Control Commission’s peacekeeping mission in Vietnam set up through the Geneva Accords, which split Vietnam into north and south in the 1950s to the 1960s, before war broke out.

Known as “Tex,” because of the cowboy boots he wore when he enlisted, Gehman later switched to helicopters following a test flight that went wrong.

“He desperately wanted to be a photographer,” son Kirby said. “He got a camera from the Eaton’s catalogue for $30.

“But when he signed up for the air force, they said they didn’t have room for a photographer… But he always loved photography and he always liked taking photographs,” Kirby said. “I think he wanted to be an artistic type, but then he was pushed to that macho role.”

Gehman grew up on a farm outside Chilliwack, B.C.

In a biography, he put it bluntly: “Our farm really sucked.”

“I don’t know the real financial outcome of the many years of toil, but I have a feeling that it was negative… The flat part of our acreage was a ledge, or slump, from a mountain of shale and rock. My dad was very enthusiastic about growing things. There were acres of plum trees, cherries of several varieties, and some good land wasted in squirrel food — hazel nut trees.”

Kirby said his dad only escaped taking over the farm because of how young he was when he started school. “Because he graduated at an early age, he joined the military when he was 17. His dad died shortly after that, and he stayed in the military. But if he had been home helping his dad when he died, he never would have got off the farm.”

Gehman not only flew F-86 Sabres and CF-104 Starfighters during his military career, he would also test pilot them if there was a problem. During one flight, he found out exactly when the engine would stop.

“He had to bail out,” Kirby said. “He was confident he had a malfunctioning ejection seat. His helmet was pulled off and the microphone dragged across his face and bloodied his face and his eyeball. He looked horrible.”

Gehman landed in trees, made his way down, built a fire, and waited to be found.

The plane “went nose into the ground,” he said. “The fire baked the area into a brick and they had to extricate it. The wreck was only 12 to 14 feet long.

“But they found out an O-ring had been improperly installed and other aircraft were like that and they made changes.”

Soon after, Gehman made the switch to helicopters and later became an instructor at Portage la Prairie.

While serving, he met his future wife, Elizabeth, who was born in Scotland and was continuing her nursing training in the RCAF. They married in 1963, and were together until 2020, when she died at 83.

After leaving the military, Gehman was hired by Transport Canada, where he used his knowledge of planes as a civil aviation inspector. When Gehman finally retired, his flying continued, albeit on a much smaller scale, with radio controlled model airplanes as part of the Brady Road R.C. Club.

Gehman was waiting in a Winnipeg hospital to be panelled for a long-term care home when, because of the crush of COVID-19 patients, he was sent to a medical facility in western Manitoba, where he eventually contracted the virus.

“They flew him there,” Kirby said. “It turned out to be his last flight.”

Bernice Oleschuk

Bernice Oleschuk was taken twice from her family.

The first time was by Lewy body dementia; the second by COVID-19.

Before Oleschuk, who died Feb. 9 at 98, faced either of them, family said she lived a long and wonderful life.

“She loved romance books,” daughter Sandra Smerek said. “She always had a stack of Harlequin books.

“I don’t know why, but she loved those kinds of books. She was a great reader, right up until she passed.”

Oleschuk was born in Harding. Her dad was a tinsmith, and they moved to Winnipeg, in particular East Kildonan, when she was a child.

She attended St. Saviour’s church and sang in the choir. Her voice was so good Oleschuk competed as a soloist and won several singing competitions at the Manitoba Music Festival.

Oleschuk was out bike riding with friends, when she met the person who would change her life.

“She was out and she met my dad,” Smerek said. “She always said, ‘I met him on a street corner.’”

She became engaged to Stan in 1943, but he went off to war. After he returned, they married in 1947. “She had told him he had one year to get his act together and marry her or he would be out of luck,” Smerek said.

Oleschuk had worked as a clerk at Eaton’s and the Bay when she was single, became a stay-at-home mother until later getting a job at Plaza Drugs.

“She did everything there,” Smerek said. “She practically ran the place. She worked for two druggists and she did all the ordering, ran the post office… She was the heart of the store.”

”She had a good long life, but not long enough for me.”–Sandra Smerek

Oleschuk retired in 1985, after the first grandchild was born, so she could become a full time babysitter and grandmother.

After her husband retired, the couple spent several winters in Phoenix, and later Victoria. The couple also loved going on cruises: the Caribbean, Alaska, Hawaii, and, their favourite, through the Panama Canal.

They were married for 64 years until Stan died in 2011.

“They were a real team,” Smerek said. “I always thought when one passed away the other wouldn’t be far behind. They were attached at the hip.”

Oleschuk continued living on her own for a few more years until dementia began taking her away, bit by bit.

Oleschuk went to live at the Irene Baron Eden Centre and then, her final residence, at nearby River East Personal Care Home.

“She had a good long life, but not long enough for me,” Smerek said. “I miss her a lot.”

Luigi D’Abramo

Luigi D’Abramo turned the key and locked his restaurant Dec. 17, to concentrate on Christmas party catering for two weeks. He didn’t return.

D’Abramo, 82, died in St. Boniface Hospital on Feb. 7, after a six-week battle with COVID-19.

It’s a sign of how sudden D’Abramo’s death that the restaurant hadn’t reopened almost a month after his death.

“The restaurant was in his name only,” daughter Emily D’Elia said. “Even my mother’s name (spouse of 60 years) wasn’t on it.

“My brother and I are trying to get ownership of the restaurant, but he was listed as the sole proprietor.”

D’Abramo was born in Campochiaro, Italy, on Sept. 22, 1939. When he was 13, his parents and two siblings moved to Canada.

“They came to Winnipeg because they were told to,” D’Elia said, noting federal officials made the decision.

D’Abramo began working in the restaurant business, learning at the Marlborough Hotel.

“He started off as a cook,” D’Elia said. “His mother was a really good cook, it was just in his blood.

“And his dad was a cook, too. He worked at the Royal Alexandra Hotel. When my dad opened his restaurant, he worked at my dad’s restaurant, too. When my dad did catering, my grandfather would help. It was a family thing.”

D’Abramo was only 27 when he opened the doors to Luigi’s Restaurant on Erin Street in 1967. He later expanded into catering, at one point having a banquet hall next door.

“Sometimes we had two banquets going on at the same time,” D’Elia said, adding her dad opened the restaurant because he like being his own boss.

“He didn’t want to answer to anyone. He was married to his work. My mother would complain he spent more time at the restaurant than at home.”

In the early days, the restaurant was open until 10 or 11 p.m., but, because it was in an industrial area, through the years, he reduced it down to breakfast and lunch.

Through the years, along with his brother, D’Abramo owned other businesses, including the Concord Motor Hotel on McPhillips Street (which he named Luigi’s Motor Inn at the time), Monterey Ranch in Headingley, and the Northgate Copa Banquet Centre.

They later split the business interests and his brother co-owns the Seasons Family Restaurant in Portage la Prairie.

The run-up to Christmas was always a busy time for D’Abramo’s catering business, so he always closed the restaurant for two weeks — even setting up a cot so he could get up early to begin putting turkeys and roasts in the oven.

D’Elia figures it was during this time her dad contracted COVID-19. All three of his delivery drivers also came down with it.

Retirement was never a word in her dad’s vocabulary, she said.

“He told my mom: you’re going to find me dead in the restaurant some day. He didn’t want to retire because then he would be old.”

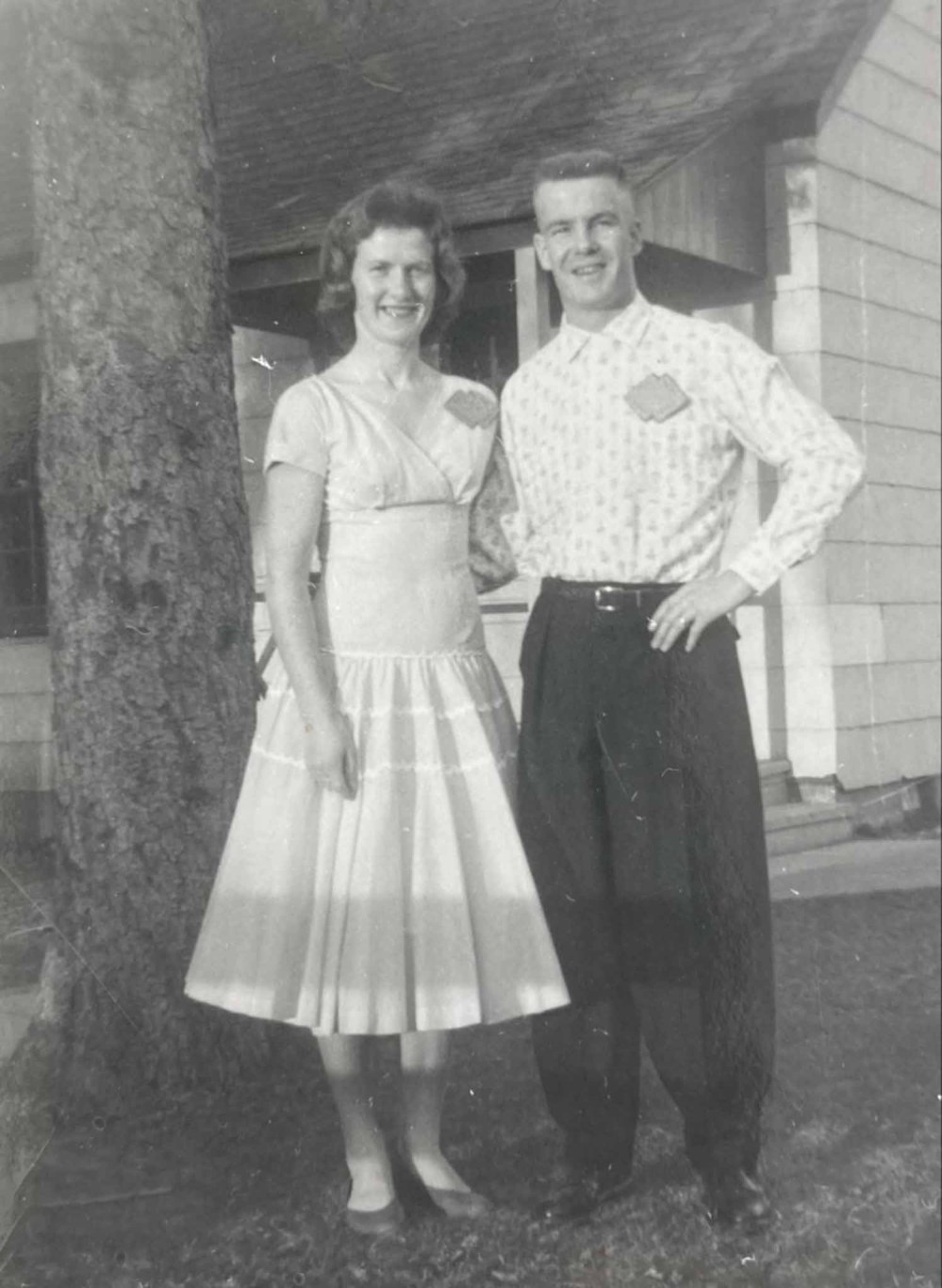

Mary Cartlidge

It wasn’t a strike or a spare that brought love to Mary Cartlidge — it was the pins themselves.

Cartlidge, who was 91 when she died of COVID-19 complications Feb. 11, was working as a pin girl at a bowling alley in Portage la Prairie, replacing knocked-over pins by hand, when she met future husband Al.

“It was more than pin money she got,” joked Thora Cartlidge, one of her three daughters.

“He noticed my mother, who was two lanes over. Her dog, Stubby, had just died and she was crying. Well, one thing led to another and in a couple of weeks they were dating. A year later, they were engaged and two years later, they were married.”

Cartlidge turned 19 nine days after their wedding. The couple were married 69 years until Al died in 2018.

“It was that glance across the bowling lane which tied a knot around them,” Thora said. “They were inseparable through their lives.”

Cartlidge was born in Portage la Prairie on Oct. 19, 1930, to a couple who came to Canada from Denmark. One of four girls, she was active in track and field during school. While she never owned a horse herself, she developed a life-long love of them, riding and showing them at regional fairs.

“Anytime she had an opportunity to ride, she would, whether in Cuba on vacation or in Australia where my dad did a teacher exchange. The horse connection was always an important one for her,” Thora said.

Al worked as administrator of the Manitoba Home for Boys (now Agassiz Youth Centre), later at the Selkirk Mental Health Centre and then in teaching; Cartlidge worked as a teacher’s aide while volunteering for numerous organizations.

She also began looking after children.

“They fostered kids in need or in distress or in trouble, at a time when service agencies were just forming,” Thora said. “(Along) with one teacher, almost every year she took a group of restless kids, authorized by the parents, to go camping. They went as far as Jasper (Alta.). With no formal training, she was active in influencing kids’ thinking of what’s valuable in life.”

And those children remembered her.

“Several years later, at her personal care home, many of the staff members remembered my mom on the playground, as playground staff or on one of the camping trips,” Thora said. “She had an inclination to step up and give a hand. She would say, ‘Stay still too long and your feet will stay in cement.’”

Her care home was able to keep COVID-19 at bay until December, when the Omicron variant came to Manitoba. Cartlidge became infected in early January.

“She had been looking forward to restrictions being lifted this summer, so she could be wheeled down to the library, to my sister’s place, and… the restaurant at the golf course,” Thora said.

“She tested negative at the end of the first week of February, but the fatigue and after-effects of COVID took her down. It shortened her life.”

kevin.rollason@freepress.mb.ca

Manitobans who contracted COVID early reflect two years later

Posted:

Al Bradbury was celebrating his retirement from the Winnipeg Police Service with his wife and two friends on what was to be a spectacular trans-Atlantic cruise from the Caribbean to the Mediterranean Sea two years ago.

Kevin Rollason is a general assignment reporter at the Free Press. He graduated from Western University with a Masters of Journalism in 1985 and worked at the Winnipeg Sun until 1988, when he joined the Free Press. He has served as the Free Press’s city hall and law courts reporter and has won several awards, including a National Newspaper Award. Read more about Kevin.

Every piece of reporting Kevin produces is reviewed by an editing team before it is posted online or published in print — part of the Free Press‘s tradition, since 1872, of producing reliable independent journalism. Read more about Free Press’s history and mandate, and learn how our newsroom operates.

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.