Inside the war on hate Reporter Ryan Thorpe re-examines the 2.5-year journey of Patrik Mathews — from neo-Nazi to U.S. prison inmate — and how authorities are coming to grips with domestic terrorism

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 19/11/2021 (1484 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

For three years, the high priests of the QAnon conspiracy-theory movement and other far-right crackpots and bigots had preached about a storm on the horizon.

On Jan. 6 — fuelled by lies peddled by the 45th president of the United States of America and his sycophantic allies — the prophecy became self-fulfilling.

Watching from Canada, it seemed the United States was engulfed in flames.

They came from all over the country, loaded into cars, trucks and buses with weapons, banners and Confederate flags, intent on overturning the results of the 2020 presidential election.

It was a violent assault on democracy, the culmination of an improbable story that began June 16, 2015 when Donald J. Trump rode down an escalator in New York City to the tune of Winnipeg legend Neil Young’s Rockin’ in the Free World.

When Trump announced his candidacy for the highest political office in the land, pundits in the press mostly snickered. The Republican party didn’t take him very seriously either, at first.

But students of history know anti-democratic, authoritarian movements always have an element of the farcical in them. We laugh them off at our own peril.

By the time the dust settled on Jan. 6, five people were dead and 138 police officers were injured. In the next seven months, four of the officers who responded to the attack committed suicide. All told, 691 people have been criminally charged for their actions during the riot.

While some of the would-be insurrectionists likely got caught up in the frenzy of the moment, others came with violent revolution on their minds. Among their ranks were conspiracy theorists and far-right extremists, including members of the Oath Keepers and the Proud Boys.

The Trump phenomenon had long ago ceased to be a punch line; now, it was deadly serious.

In the weeks leading up to the violence, weapons were stockpiled, plans devised, maps of the building distributed and there were discussions about which politicians should be prioritized for execution. To leave no doubt about their aims, a makeshift gallows was erected on the Capitol grounds.

The Trump phenomenon had long ago ceased to be a punch line; now, it was deadly serious.

But among the far-right extremists present that day, one group — the Base — was notably absent. The Federal Bureau of Investigation had largely dismantled the organization with a sweep of arrests one year prior.

All told, eight members of the violent neo-Nazi paramilitary group had been arrested in various states. Among their ranks was Patrik Mathews, a Canadian national and former military combat engineer on the run from law enforcement.

When the images of Jan. 6 were broadcast to the world, some wondered if they were watching the beginning of the end of liberal-democratic order in America. But watching the chaos from Winnipeg, I couldn’t help but wonder about something else.

As tragic as the loss of life that day was, I couldn’t help but wonder just how much bloodier it might have been. I couldn’t help but wonder what would have happened if the FBI had not taken down the Base when it did.

As an undercover reporter, I had infiltrated the group. I knew it from the inside. I knew the depths of members’ bigotry and thirst for blood.

I knew they wouldn’t have been among those storming the doors of the Capitol. They would have been on the outskirts with their rifles trained on the crowd, fingers hovering over triggers.

This was the moment they had been waiting for.

● ● ●

When the Winnipeg Free Press exposed Mathews as an active combat engineer in the Canadian military moonlighting as a recruiter for a violent neo-Nazi paramilitary group, I had no idea the twists and turns the story would take.

I did not expect it to become a stranger-than-fiction tale with a dramatic RCMP raid, a fugitive on the run, an international manhunt, a pagan animal sacrifice, a spate of death threats, an FBI counter-terrorism investigation, murder plots and criminal proceedings in multiple states.

I did not expect to go to Washington, D.C., where I would visit the Capitol grounds, still barricaded with protective fencing months after the Jan. 6 assault.

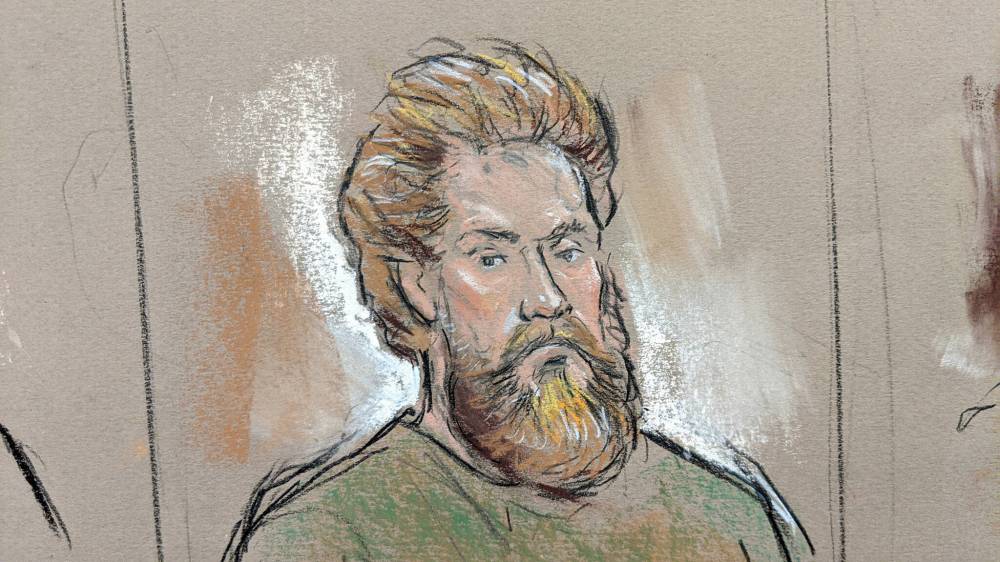

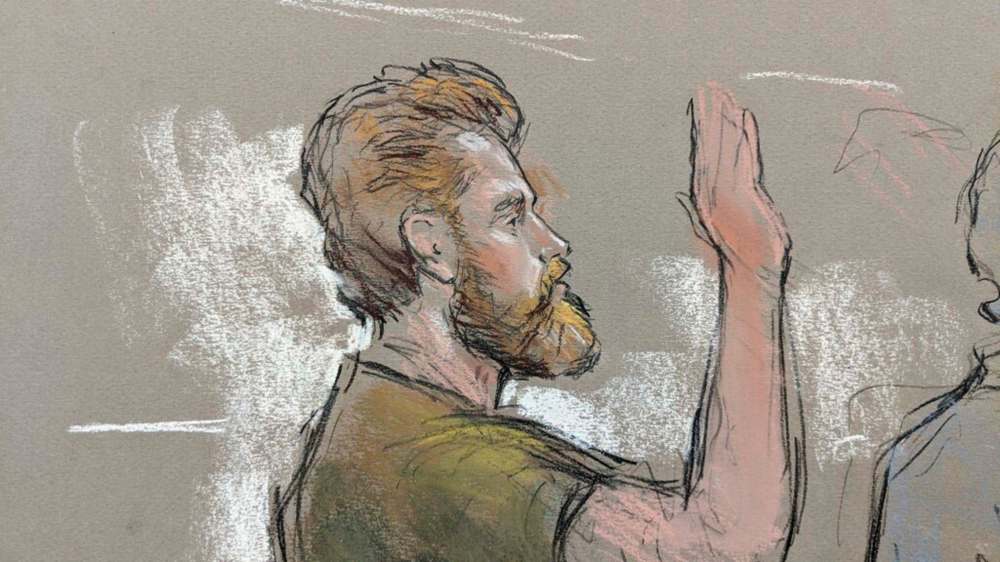

I did not expect to go to Greenbelt, Md., where I would come face to face with Mathews, his eyes burning into mine as he was led into the courtroom dressed in the orange jumpsuit of a federal prisoner.

I did not expect to go to Charlottesville, Va., where neo-Nazis and Klansmen had unleashed terror and death during the 2017 Unite the Right rally.

I did not expect to go to Richmond, Va., the former home of the Confederacy, where Mathews plotted violence and mayhem at a pro-Second Amendment rally; or to Newark, Del., where he built an untraceable assault rifle in an apartment he shared with another neo-Nazi.

And I certainly did not expect my reporting to lead me into the halls of the U.S. Attorney’s Office in Maryland, where I would sit down with the prosecutor who put Mathews behind bars, and with one of the FBI domestic terrorism teams that took down the Base.

There were other unexpected meetings, too, with the RCMP’s National Security Unit and with Canada’s spy agency, the Canadian Security Intelligence Service.

The Free Press investigation began in the late summer of 2019 with a news tip about a racist recruitment drive in Winnipeg. We chased the story in the manner we did because we felt the Base posed a serious threat to our community, particularly to racial and religious minorities.

And when we published our results, revealing that a neo-Nazi with explosives training was active in a local branch of the armed forces, the most dispiriting responses came from those among the public, military and police who downplayed or dismissed it.

Everything that transpired since our initial article, Homegrown Hate, was published on Aug. 16, 2019 has vindicated our concern. But as I’ve continued my reporting into far-right extremism in the two years since, I’ve come to learn just how predictable the initial skepticism was.

As Mark Twain said, history doesn’t repeat itself, but it often rhymes.

As Mark Twain said, history doesn’t repeat itself, but it often rhymes.

It was a cold, icy day in Munich, on Jan. 1, 1933, when Adolf Hitler awoke to headlines from the German press satirizing and mocking him in the wake of an election. The papers predicted Hitler and his party of misfits would soon be old news. Within a month, he was chancellor.

A more recent example: on St. Patrick’s Day 1996, Daniel Coleman, a foreign intelligence agent stationed in the New York Field Office of the FBI, stumbled onto the existence of a then-largely unknown terrorist organization called al-Qaida.

As detailed in Lawrence Wright’s Pulitzer Prize-winning book The Looming Tower, Coleman — to his exasperation — “couldn’t even get his superiors to return his phone calls on the matter.”

“The group was small — only ninety-three members at the time — but it was part of a larger radical movement that was sweeping through Islam… The possibilities for contagion were great… They were fanatically committed to their cause and convinced they would be victorious,” Wright wrote.

“They were brought together by a philosophy that was so compelling that they would willingly — eagerly — sacrifice their lives for it. In the process they wanted to kill as many people as possible.”

The most frightening aspect of the threat was that “almost no one took it seriously.” It was too bizarre and exotic for most people to wrap their heads around. To them, the “defiant gestures of bin Laden and his followers seemed absurd and even pathetic.”

With a few minor changes, the same could be said about the neo-Nazi accelerationist movement Mathews declared allegiance to — a small, dedicated faction of the far-right hate movement that seeks to destabilize society through acts of violence in the hopes of sparking a race war.

And when set against the backdrop of the rising tide of illiberalism around the world, and increased political polarization at home and abroad, such threats should not be laughed off or dismissed.

We have seen the results of fanatical, racist hatred in this country. From the Quebec City mosque shooting of 2017 to the London van attack of 2021, too much blood has already been spilled.

That does not mean there is a neo-Nazi hiding around every street corner. But it does mean we need to be open and honest about the levels of bigotry and hatred in our society, and to vigorously confront such prejudices whenever and wherever they rear their ugly heads.

● ● ●

Shortly before federal judge Theodore Chuang handed down a nine-year prison sentence to Mathews in a Maryland courtroom on Oct. 28, his defence attorney, Joseph Balter, offered previously unknown insights into his client’s childhood during a plea for leniency.

Mathews grew up in the Lundar area of Manitoba, where — according to Balter — he was viciously bullied as a child. He was hit and taunted by other kids on the school playground, and would often stand still, seemingly frozen, unsure of how to respond.

At some point, Balter claimed, even the parents of other children asked for Mathews to be removed from the school.

When he was seven years old, Mathews spent three weeks in a residential mental-health facility where he was diagnosed with Asperger’s Syndrome, a condition associated with challenges in social interaction and repetitive interests and patterns of behaviour.

The doctors reportedly suggested powerful antipsychotic medication to Mathews’ parents, but they ultimately declined. Another unspecified medical intervention followed two years later. This condition, Balter said, led to “rigid thinking” and “cognitive inflexibility.”

“He’s the type of person who would become obsessed with things and he’d become stuck,” Balter said.

At times, it felt like Balter’s argument amounted to: ‘Asperger’s Syndrome made my client a neo-Nazi.’ Sitting there in court listening to this, I couldn’t help but wonder how offensive this might be to the many, many people with the condition who don’t become fanatical racists.

Outside the courthouse, Mathews’ mother offered various explanations for the path her son took in life, blaming everything from violent video games, to the Canadian military, to me.

Suspiciously absent from blame was Mathews himself — a grown man who, whatever his neurological challenges, had acquitted himself well enough in the military to receive multiple promotions, and who held down a job, had a long-term girlfriend and owned a home.

There was one thing Balter said in court, however, that resonated: Mathews’ belief in neo-Nazism had been an “abstraction” that gave a “sense of purpose” to an otherwise dull and ordinary life.

Without knowing it, Balter had hit upon a question I have spent much of the past two years thinking about: what leads people to fanatically commit themselves to violent causes?

In his 1951 book The True Believer, Eric Hoffer suggested mass movements often “rise and spread without belief in God, but never without belief in a devil.”

It is clear for Mathews and the Base that devil was primarily Jews, but also racial minorities of all stripes, women and pretty much anyone who didn’t look like them — straight white men.

To read the transcripts from Mathews court case, one is struck by the level of venom and the depth of hatred in his rants. They would have fit in on the pages of the virulently antisemitic newspaper Der Sturmer in 1940s Germany.

As the English journalist George Orwell suggested, no deep psychologizing is needed to understand fascists; at the end of the day, they are just people who “long for a hierarchical society and dread the prospect of a world of free and equal human beings.”

But there may be more to it than that. Richard Hofstadter’s 1964 essay The Paranoid Style in American Politics best captures the fanatical mindset.

“The paranoid spokesman sees the fate of conspiracy in apocalyptic terms — he traffics in the birth and death of whole worlds, whole political orders, whole systems of human values. He is always manning the barricades of civilization. He constantly lives at a turning point,” Hofstadter wrote.

“As a member of the avant-garde who is capable of perceiving the conspiracy before it is fully obvious to an as yet unaroused public, the paranoid is a militant leader… Since what is at stake is always a conflict between absolute good and absolute evil, what is necessary is not a compromise but the will to fight things out to a finish.”

When I met Mathews in person, he believed I was a like-minded racist, and as a result, he opened up to me about his worldview in a way he did with few others.

I am convinced this was his mindset when he abandoned his truck near Sprague in late August 2019 and illegally crossed into the U.S. on foot.

Beholden to the fantasy a race war was on the horizon, and convinced his people were being subjected to a secret genocide, he chose to double down on his neo-Nazism.

It was about a week after the dramatic RCMP raid on his home, located on a quiet, tree-lined street in Beausejour. In addition to the firearms the Mounties seized, they also found an obsessively detailed list of mass shootings perpetrated in North America in recent decades.

Now, in Mathews, there was a new triggerman in the fight to the finish.

● ● ●

In the summer of 2019 the Canadian Armed Forces and the Department of National Defence were concocting a public relations campaign aimed at combating allegations the military had a problem with extremists in its ranks.

First there had been the Proud Boys on the East Coast who disrupted an Indigenous ceremony. Then officer cadets in Quebec desecrated a Qur’an with bacon and bodily fluids. And reservists were selling racist merchandise online.

In the wake of those incidents, anti-hate activists were publicly criticizing the Forces for turning a blind eye to hateful conduct among its members. This left the military feeling like it was being unfairly raked over the coals.

According to reporting from David Pugliese of the Ottawa Citizen based on documents obtained through access-to-information requests, the Canadian Forces and DND spent several months planning a public relations blitz to address this “reputational risk.”

The following month, the Free Press exposed Mathews, sending the military into a tailspin as it tried to explain how a neo-Nazi was trained to use explosives by the Canadian government. Ultimately, the decision was to quietly scuttle the planned PR campaign.

But the Mathews case should not have come as a surprise. Not only was it not the first time a neo-Nazi had been exposed in the Canadian Forces, it wasn’t even the first time it had happened in Winnipeg.

In September 1992, the Winnipeg Sun published a report on white supremacy in Manitoba, which included a photograph of then Pte. Matt McKay giving a Nazi salute while wearing a Hitler T-shirt in his military barracks.

A swastika flag was draped on the wall behind him, hanging openly on Forces property. One would think displaying allegiance to a regime 45,000 Canadians died fighting would result in a swift repercussions, but it didn’t. The military took no action against McKay.

“As long as they don’t do anything illegal, they can do anything they want. This is a free country,” Capt. Daniel Lachance said at the time.

That was echoed by a DND spokeswoman who said: “We do not have a policy. It is not illegal.”

When shown the photograph of McKay, then-defence minister Kim Campbell said his neo-Nazi activity, which included associations with racist skinhead gangs and the Manitoba chapter of the Ku Klux Klan, amounted to “youthful folly.”

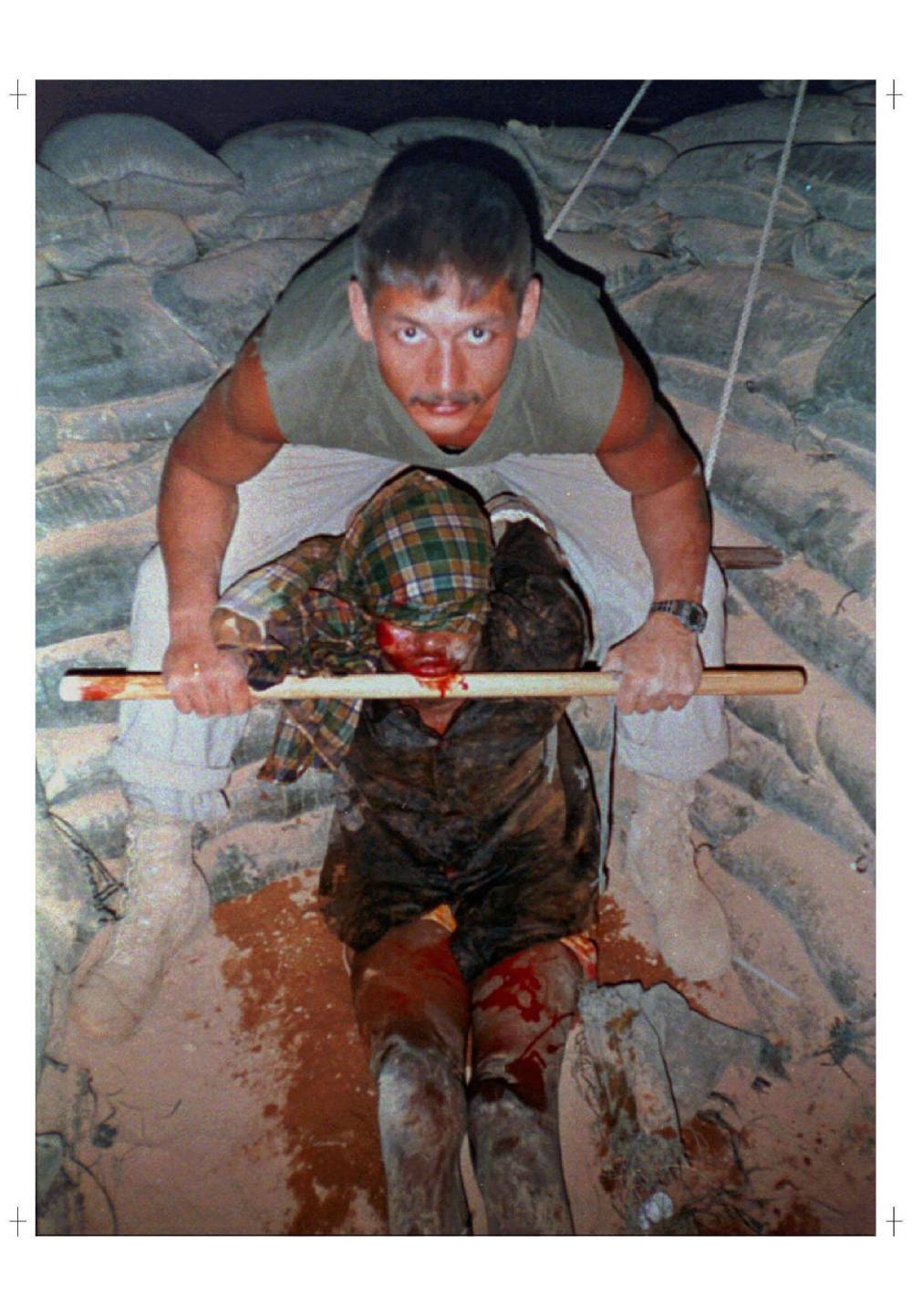

Instead of being punished, McKay was rewarded; he was promoted to corporal and sent to serve on the ill-fated 1992 United Nations peacekeeping mission in Somalia. The results were tragic and utterly predictable.

The mission descended into an orgy of violence, with McKay’s Airborne Regiment (since disbanded) torturing and murdering a Somali teenager named Shidane Arone. Video footage would later surface of McKay using racial slurs and stating his desire to kill more locals.

During the ensuing inquest — which marks one of the worst scandals to ever pock the reputation of the Canadian Forces — it was revealed top military brass were complicit in covering up the open white-supremacist activity that had transpired on their watch.

Sadly, McKay’s alleged violence was not limited to his time in Somalia. Blood had also been spilled in Winnipeg.

On June 30, 1991, Gordon Khutey was walking along the Assiniboine River near the Osborne Street bridge in an area then known as the “gay stroll” when he was attacked. Khutey was beaten and stoned to death, and his body was thrown in the river.

The Winnipeg Police Service did not close the case until March 1996, when McKay and three associates — all alleged members of a neo-Nazi skinhead gang — were charged with murder.

But those charges were stayed by Crown prosecutors when a key police witness was discredited during the trial. As a result, McKay and the others walked.

In the aftermath of the Somalia Affair, the military vowed to get serious about hateful actors within its ranks in the hopes of avoiding a repeat of the scandal.

But much like with a culture of sexual misconduct in the military — which first came to light in the early-1990s and continues to plague the Forces — recent events have shown that little progress was made.

In 2018, a military police report — later released through a freedom-of-information request — found 53 members of the Forces had been found to engage in hateful conduct or be bona fide members of hate groups during the five-year period of study.

Among those hate groups was Atomwaffen Division, a neo-Nazi accelerationist outfit similar to the Base. While the vast majority of the men and women in the Canadian Forces serve with honour and distinction, there is little doubt the report only scratched the surface of the problem.

Most remarkably — just like with McKay decades earlier — 30 of the 53 members remained on active duty. No action was taken against them.

And instead of grappling with the reality of extremism within its ranks by creating new policies aimed at weeding it out, the military spent the summer of 2019 planning a PR blitz to push back against anti-hate organizers complaining about the problem.

After Mathews was exposed, the Forces gave academic Barbara Perry, the director of the Centre on Hate, Bias and Extremism at Ontario Tech University, a research grant valued at $750,000 to investigate the matter.

Perry helped the military craft policies clearly defining hateful conduct among its members, a welcome development.

But the real question is why — in the 26 years between the sordid tale of Matt McKay and the saga of Patrik Mathews — had the military not implemented such policies on its own?

● ● ●

When al-Qaida terrorists slammed two passenger airplanes into the World Trade Center buildings in New York City on Sept. 11, 2001, the course of history was changed. For an entire generation, there is before 9/11 and there is after. Nothing has been the same since.

National security organizations in the United States, Canada and Europe scrambled to shift their focus to Jihadist extremism. But this left them with a serious blind spot when it came to homegrown, far-right terrorists.

According to data from the Center for Strategic and International Studies, white-supremacist, anti-Muslim and anti-government extremists have been the chief driver of terror attacks in North America during the past decade.

Now concerns are being raised as to what extent agencies — chiefly the FBI and CIA in the U.S., and the Canadian Security Intelligence Service — have caught up with the times. There is evidence to suggest the FBI is increasingly worried about the threat of far-right actors south of the border.

In March, FBI Director Christopher Wray addressed Congress for the first time since the Jan. 6 assault on the U.S. Capitol — an event he bluntly characterized as “domestic terrorism.” He warned that white-supremacist terror was a growing threat.

“Jan. 6 was not an isolated event. The problem of domestic terrorism has been metastasizing across the country for a long time now and it’s not going away anytime soon,” Wray said.

In an interview with the Free Press, Thomas Windom, the Assistant U.S. Attorney for the District of Maryland, who prosecuted the case against Mathews, said his office has seen a definite spike in homegrown terror cases.

“For a period of time in this district, we were looking at ISIS, we had al-Qaeda, other material support of foreign terrorist organizations. I don’t think we’ve had one of those in the last few years,” Windom said.

“The ones we’ve had in the last few years, we have stated and the court has found, were domestic terrorism.”

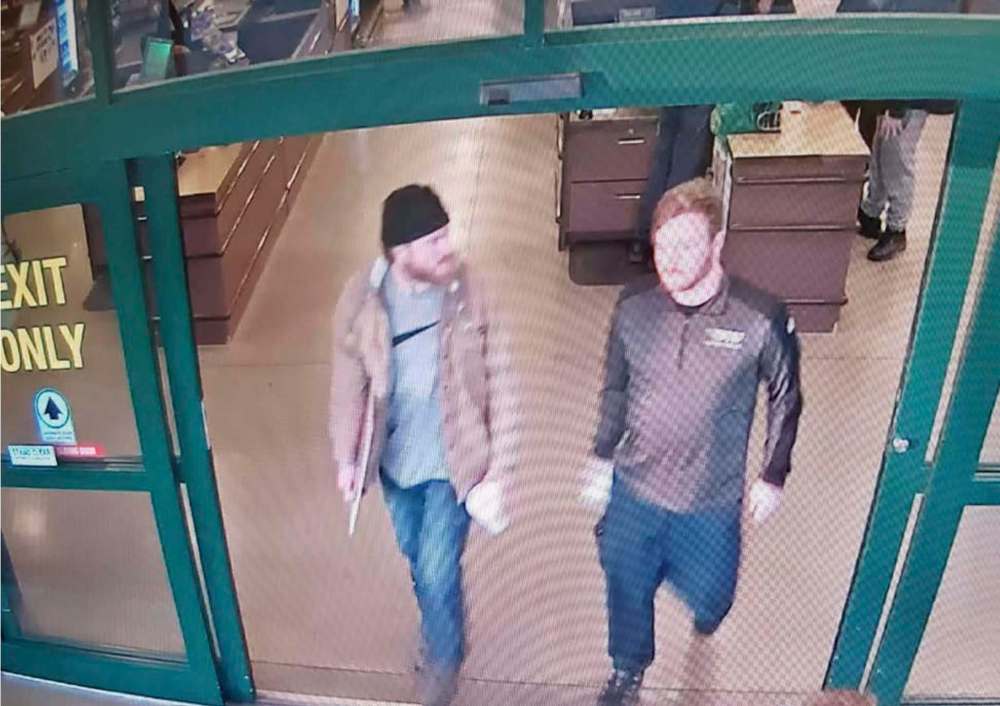

The day after Mathews was sentenced to nine years in prison, I sat down with the FBI domestic terrorism team that arrested him: Supervisory Special Agent John Phillips, Special Agent Rachid Harrison and two of their colleagues who can’t be named.

The team walked me through their investigation into Brian Lemley Jr. — a veteran of the U.S. war in Iraq, and Mathews’ main co-conspirator — which took an unexpected turn when a Canadian national illegally entered the country and waltzed into their crosshairs.

“I don’t think it’s a good thing when you add an extremist to an investigation, but it is true that it accelerated the investigation,” Phillips said.

Work on the case began sometime in mid-2019 when Lemley first showed up on their radar. Before a domestic-terror probe can be opened, there must be proof of a motivating ideology, a clear threat of violence and evidence a federal crime has been committed.

After Mathews entered the U.S., Lemley drove about 1,000 kilometres from Maryland to Michigan to pick him up, providing him safe harbour in various states in an attempt to evade law enforcement before travelling to a paramilitary training camp in Georgia.

Eventually, the two men rented an apartment in Delaware, which served as their base of operations.

“One of the things that was most concerning about Patrik Mathews was that in his mind he had no place to go back home to. He believed he was facing criminal charges in Canada, whether that was true or not. His belief was that he was a fugitive from Canada,” Phillips said.

“He knew he was an illegal in the United States. He had no place to go back to. He didn’t have a spouse. He didn’t have children. He had limited work prospects in the United States. So he was very dangerous from our standpoint.”

After securing search warrants, the FBI conducted a “sneak and peek” search — authorizing police to physically enter into private premises without the owner’s or the occupant’s permission or knowledge; generally, such entry requires breaking and entering — on their apartment, and also installed audio and video surveillance equipment.

“After that search it was very clear they had the ability and the parts to make a firearm. It was very clear they had tactical gear, they had Base patches, Base flyers,” Harrison said, adding they watched Mathews build an untraceable assault rifle on CCTV surveillance.

As the FBI watched on, the neo-Nazis cooked up race-war fantasies, plotted prison breaks and terror attacks and amassed an arsenal that included two guns, more than 1,000 rounds of ammunition, communication devices and enough pre-cooked meals to keep them fed for several months.

In the U.S., there are no federal domestic-terrorism statutes on the books. Instead, prosecutors have to charge underlying offences — in Mathews’ case, gun crimes — and then request the judge impose a terrorism “sentencing enhancement” on the defendant.

For Phillips, the fact the judge imposed two terrorism-sentencing enhancements on Mathews and Lemley was a win for his team.

“That might seem like something that is very common in the United States, but it’s not. It’s very rare. It’s one of very few cases where the terrorism enhancement was agreed upon for a domestic-terrorism case. One of very few,” Phillips said.

Meanwhile, in Canada, questions remain about how serious our national security organizations are taking the far-right terror threat.

On June 1, 2019, Mathews was stopped by Canadian Border Services Agency officials after attempting to return to the country from the U.S.

Among the materials found in his vehicle were propaganda posters warning of a white genocide and a list of mass shootings. When pressed by border officials, Mathews kept changing his story as to where he was coming from and what he’d been doing in America.

The agents sent him on his way. One can’t help but wonder if a young Muslim man would have been given the same treatment if found with Jihadi propaganda and a handwritten list of suicide bombings.

When Mathews was exposed by the Free Press two months later, the RCMP moved quick to seize his firearms, but they released him without charge after a brief stint in custody. And after they cut him loose, it’s clear they were not keeping a close eye on him, given he was able to flee the country.

Last May, the federal government officially designated the Base, alongside a score of other extremist groups, as a terrorist organization.

In its 2018 public report, CSIS said it was “increasingly preoccupied by the violent threat” posed by extremists motivated by racial hatred, ethno-nationalism and misogyny. In 2020, the agency noted Canada’s “key national security threats… accelerated” during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Last May, the federal government officially designated the Base, alongside a score of other extremist groups, as a terrorist organization.

These are promising signs, but given the lack of transparency national security agencies in Canada operate with, it’s hard to know for certain how many resources they are devoting to combatting the threat.

● ● ●

In 1934, members of the Nationalist Party of Canada, a collection of pro-Hitler and pro-Benito Mussolini fascists, gathered in Winnipeg’s Old Market Square.

The party had been founded a year prior by William Whittaker, a veteran of the First World War and a former organizer for the Ku Klux Klan.

All told, between 75 and 100 brownshirts stalked the park that day. In response, more than 500 anti-fascists showed up.

In the clashes that followed, NPC members were physically removed, a few were arrested and Whittaker fled.

It would come to be known as the Battle at Old Market Square, and the lessons learned that day were passed down to subsequent generations of local anti-racists: namely, fascists will never be allowed to openly organize in Winnipeg.

In 2017, I got my first experience reporting on the far right when a racist organization announced plans to hold a rally on Portage Avenue. Local anti-racists mobilized hundreds of counter-protesters and the demonstration was shut down.

Instead of a rally for hatred and bigotry, the afternoon turned into a celebration of the city’s diversity.

There is a long and storied tradition in journalism of hard-charging reporting on fascism; this story is but a minor footnote.

During the rise of the Nazi party in Germany, Edgar Mowrer, a correspondent for the Chicago Daily News, fearlessly produced a series of investigative reports from Berlin.

Mowrer managed to cut through the official explanations for the anti-democratic changes happening in Germany, winning a Pulitzer Prize in the process, and so enraging Nazi officials that many of his friends and colleagues worried his life was in peril.

The German ambassador to the U.S. told the State Department Mowrer’s safety could no longer be guaranteed. Mowrer would only agree to leave Germany on the condition Paul Goldmann, an elderly Jewish journalist imprisoned by the Gestapo, be released.

So desperate were the Nazis to get Mowrer out of the country, they met his demand.

As he prepared to leave, a Nazi official was tasked with trailing Mowrer to the station to make sure he boarded the train. As he did, the official asked when he would be returning to Germany.

“When I can come back with about two million of my countrymen,” Mowrer said.

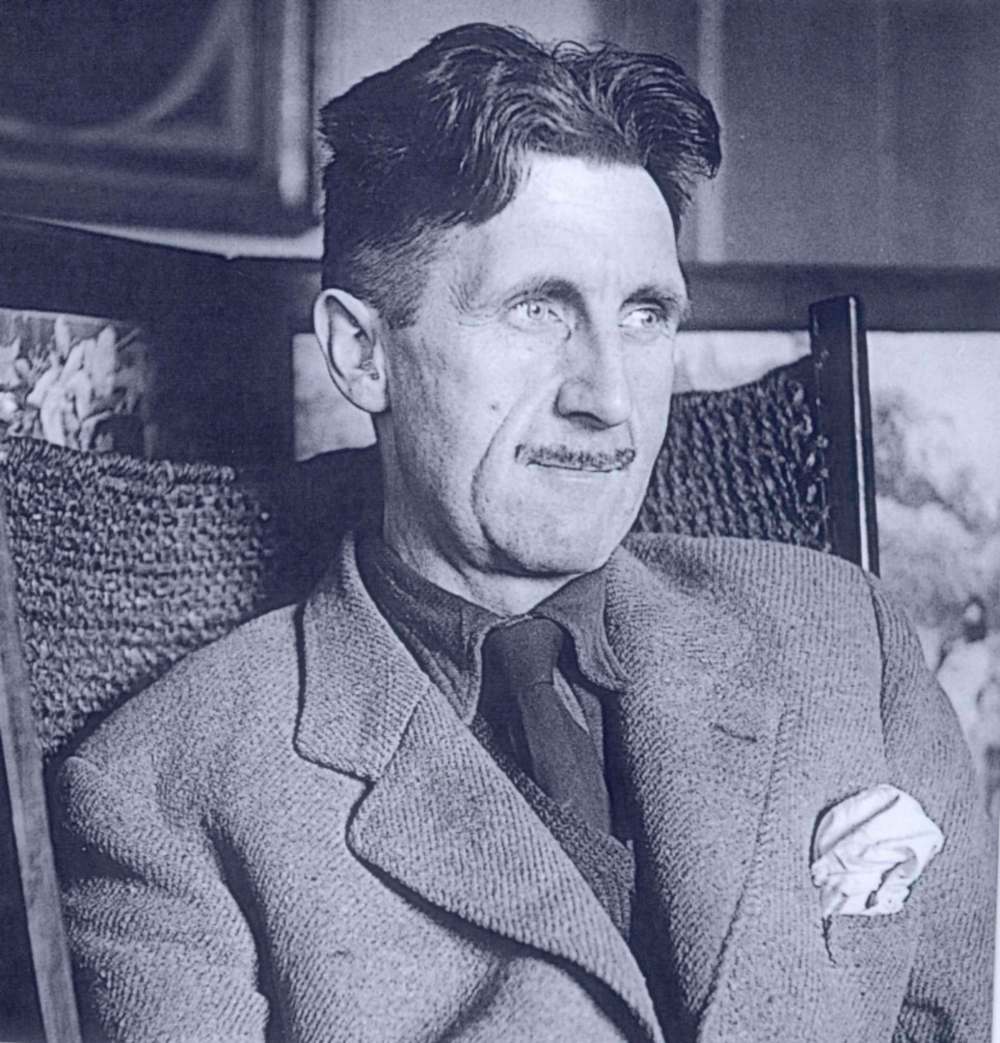

Or there is my personal hero, George Orwell, who was pulled into the Spanish Civil War — the anti-fascist struggle that served as the dress rehearsal for the bloodier battle that followed — when the clashes began in 1936.

“When the fighting broke out… it is probable that every anti-fascist in Europe felt a thrill of hope. For here, at last, apparently, was democracy standing up to fascism. For years the so-called democratic countries had been surrendering to fascism at every step,” Orwell wrote.

“The Japanese had been allowed to do as they liked in Manchuria. Hitler had walked into power and proceeded to massacre political opponents of all shades. Mussolini had bombed the Abyssinians while fifty-three nations made pious noises ‘off.’

“But when Franco tried to overthrow a mildly left-wing Government the Spanish people, against all expectation, had risen against him. It seemed — possibly it was — the turning of the tide.”

Orwell arrived in Spain with “some notion of writing newspaper articles,” but immediately joined a militia, as it seemed to him the “only conceivable thing to do.” He began writing his account of the war in the trenches, scribbling on scraps of paper and the backs of envelopes.

In the spring of 1937, a fascist sniper shot him in the neck.

“It was the sensation of being at the centre of an explosion. There seemed to be a loud bang and a blinding flash of light all around me, and I felt a tremendous shock — no pain, only a violent shock,” Orwell wrote.

Miraculously, he survived, fleeing the country after his militia was outlawed.

None of this is to compare what I did to the work of Mowrer or Orwell — in fact, my intention is precisely the opposite. The risks I took investigating the Base were minor compared to the great risks many journalists before me have taken. I am not a courageous person.

Nor is my intention to compare the threat the Base posed in Winnipeg to the threat organized fascism posed in 20th-century Europe. Rather, it is to highlight the chief lesson learned in the fight against fascism last century: unless it is opposed, it will spread and violence will follow.

Mathews has been behind bars in a U.S. federal prison since his arrest in January 2020. He has applied to serve his sentence as near to Minnesota as possible, so he can be closer to his family. I hope for his sake that request is granted.

Since he pleaded guilty to felonies, Mathews cannot appeal his convictions, but he can appeal his sentence. Should he do so, the case will go before a panel of judges in Richmond, Va. — the same place he plotted racial violence.

In some sense, Mathews and I will forever be inextricably linked. I believe in redemption, and my hope for him is that he can be de-radicalized and reorient his life in a positive direction after his release. Maybe one day I’ll even get to speak to him.

My time as a crime reporter taught me that many of the best anti-gang activists are former gang members; likewise, many of the best anti-extremist activists are former fanatics. There is genuine possibility for life after hate.

For Mathews, however, that day remains a long way off.

ryan.thorpe@freepress.mb.ca

Twitter: rk_thorpe

Homegrown hate: Coverage of a neo-Nazi recruiter in Winnipeg

Posted:

Read Ryan Thorpe's story on infiltrating a neo-Nazi paramilitary group, and the Free Press' follow-up coverage.

Ryan Thorpe likes the pace of daily news, the feeling of a broadsheet in his hands and the stress of never-ending deadlines hanging over his head.

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.

History

Updated on Sunday, November 21, 2021 9:12 AM CST: Fixes typo.

Updated on Sunday, November 21, 2021 9:42 AM CST: Fixes typo.