The belle of Broadway The Fort Garry Hotel's regal facade and grand interior hearken back to a more glamorous time

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$1 per week for 24 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $4.00 plus GST every four weeks. After 24 weeks, price increases to the regular rate of $19.95 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.99/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19.95 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 19/07/2021 (1698 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

When you’re wedged into a middle seat on a packed airplane, sustained only by bad coffee and a packet of pretzels, glamorous travel can seem like an impossible dream.

But around the turn of the 20th century, luxury train journeys across Canada involved roomy sleeping berths, white-linen dining service and observation cars with expansive windows that framed the changing views. For those who could afford it, the journey was as pleasurable as the destination.

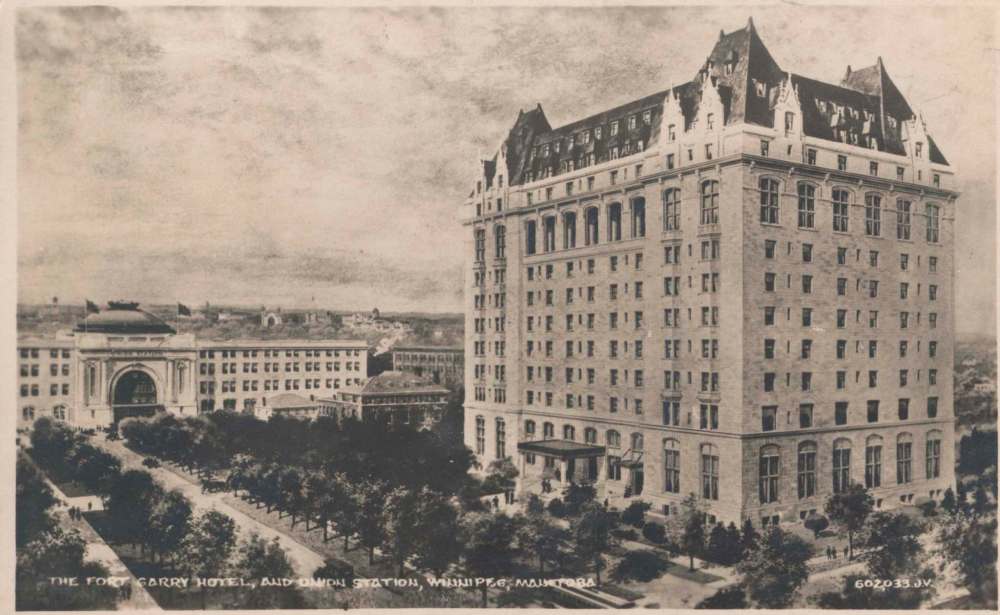

If you were making a stop in Winnipeg in, say, 1915, you could pull into Union Station, a Beaux-Arts beauty built by the firm behind New York’s Grand Central Terminal, and then take a horse-drawn carriage over to the Fort Garry Hotel, designed by Montreal-based architects George A. Ross and David H. MacFarlane and constructed for the Grand Trunk Pacific Railway from 1911 to 1913.

The glorious age of rail touring is gone now, dented first by the Depression and then overtaken by the postwar expansion of automobile and airplane travel. But the Fort Garry Hotel still stands, its elegant exterior more or less unchanged through cycles of decline and revival, through dazzling Jazz Age highs and shabby 1980s lows. For more than a century, this landmark hotel has reflected the changing face of our city.

According to the triumphant national mythology of the 19th century, Canada was unified by the “steel spines” of its rail lines. These lines were punctuated by grand railway hotels, the so-called “Castles of the North.” Starting with the dramatic Château Frontenac in Quebec City, completed in 1893, many of these structures were built in the Château style — sometimes termed Railway Gothic — which combined imposing, often fortress-like exteriors with opulent and elaborately detailed interiors.

Some, like the Banff Springs Hotel, promised civilized pleasures against a wilderness backdrop, while others anchored growing city centres.

Marking the physical connection of our country from East to West Coast, these structures also forged a symbolic bond. The Château style is now recognized as a distinct Canadian architectural form, though it is one of the peculiar paradoxes of Canadian identity that an attempt to encourage and express nationalism through architecture would involve references to French châteaux, Bavarian castles and elements of the Scottish Baronial style.

At 58.5 metres, the Fort Garry Hotel was one of the tallest buildings in town when it was first constructed. On the relatively plain stone facade, lines of windows lead the eye upward in the manner of an austere turn-of-the-20th-century skyscraper, but then we get to that elaborate, wonderfully fanciful roofline, with its gables and turrets and steep-pitched, copper-clad peaks.

Just as important as the building’s impressive exterior scale are all the little interior details — the carved keystones, bronze balustrades, fluted oak columns, stained-glass transoms and gilded ceiling medallions.

When we think about hotels, we usually think first of travellers, and through the decades, famous guests at the Fort Garry have included Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, Louis Armstrong, Laurence Olivier and Joan Crawford. But the hotel has also been a gathering place for Winnipeggers, as the site of civic functions, business conferences, charity fundraisers and just a lot of really swell parties.

There’s a lot of infrastructure undergirding this service. Like many early railway hotels, the Fort Garry was built as “a city within a city.” Hidden away from the posh public areas were the labour and resources that made all that luxury possible — vast laundries and kitchens, an artesian well, a heating plant, an in-house printing press, a butcher, a bakery and a mushroom cave (!).

The hotel’s gilded-age glories — and the nuts-and-bolts systems required to keep it going — eventually fell into disrepair, and by the early 1990s, a series of owners had faced tax wrangles and financial problems. There were worries the Fort Garry might be shut down.

In 1993, Ida Albo and Richard Bel, along with the Quebec-based Laberge Group, took over. Presiding over extensive renovations, they have honoured the hotel’s storied past while bringing it into the 21st century. (It is now the Fort Garry Hotel, Spa and Conference Centre.)

Part of that mission means redefining what luxury might mean for contemporary guests. The 10th floor, for example, which once housed a small army of live-in chambermaids, is now a spa and hammam. As Albo points out, for many modern travellers — and Winnipeggers thinking about staycations — luxury might mean vegan or gluten-free menu options, or wellness rooms on each floor, a project currently underway.

“We feel blessed to have the opportunity to put a stamp on the building for the last quarter-century,” she states. “It’s a privilege to be able to do that.”

It wasn’t always easy. “Our first Hydro bill was more than our room revenue,” Albo recalls. “This is not for the faint of heart.”

Through it all, the building itself has inspired them — “just the grandeur, inside and out,” Albo says. Her own favourite spot is the loggia running between the ballroom and the banquet hall on the seventh floor, with its high, cross-vaulted ceilings and stunning city views.

“When you think back to the history of the hotel, when it was being built, Winnipeg was on par to be like New York or Chicago,” Albo explains.

“We didn’t make it,” she adds with a laugh. “But the hotel’s still here.”

alison.gillmor@freepress.mb.ca

Studying at the University of Winnipeg and later Toronto’s York University, Alison Gillmor planned to become an art historian. She ended up catching the journalism bug when she started as visual arts reviewer at the Winnipeg Free Press in 1992.

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.

History

Updated on Tuesday, July 20, 2021 8:44 AM CDT: Corrects spelling of Winnipeg