Winnipeg’s downtown is down, but not out The pandemic has emptied streets and offices, but experts say with help, city's centre can rebound

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$1 per week for 24 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $4.00 plus GST every four weeks. After 24 weeks, price increases to the regular rate of $19.95 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.99/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19.95 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 09/04/2021 (1794 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

The convenience store cashier sees everything on his corner of Graham Avenue. His view is good: behind the register, he sits on a fading vinyl stool that pivots, and if he turns his head over his left shoulder, his eyes look right out toward the bus stop. If he’s lucky, the benches are full of university students or harried office workers, and the No. 18 is running a bit late.

If that’s the case, the shop door will swing open, and the cashier will be a very busy man, selling cans of Coca-Cola and energy drinks, packs of gum and cigarettes, a few lottery scratchers, a loaf of bread, a stick of deodorant, whatever anyone needs. For most of the day, the corner is somewhat quiet, but for a few short bursts — one in the morning, shortly after he opens up at 5:30 a.m., another at lunchtime, and another when people start to go home, around 3:30 p.m. — the intersection of Graham and Vaughan is a very loud place, and business is as steady as the pace on the sidewalk.

“After six o’clock, it always slows down,” says the cashier, who’s worked at the Graham Convenience Store for five years. For the last 12 months, it’s felt like after six o’clock.

Every person has a unique vantage point of how the pandemic has shifted the world, but the cashier, who didn’t want his name shared, has had a crystal-clear perspective on the way COVID-19 has changed Winnipeg’s downtown. All he’s had to do is turn his head, look through his window and watch the clock. He has anecdotal evidence, such as the quiet. But he also has empirical evidence, such as the relatively empty street corner and the number of customers as compared to his first four years at the store.

He often counts them: before all this, as many as 250 to 300 unique visitors walked through the door on an average weekday. “Now, Monday to Friday, anywhere from 50 to 100 (each day),” he says. He breaks it down by the hour sometimes, just to change things up. Any way he measures, fewer people are around.

“This convenience store serves about 95 per cent the same people every day,” he says. “The same people going to work, the same people going to the university, the same people taking the same bus. When they come in, I already know what they need. It’s the same people every day.

“But many aren’t here anymore,” he says. “Lots of friends I haven’t seen lately.”

● ● ●

For nearly as long as the downtown has existed, there have been worries over its potential demise.

The central business district flourished in the late 19th century: Winnipeg was strategically well-positioned as an economic hub, becoming a vital channel in agriculture, railway, wholesale and finance. It was soon dubbed the “Gateway to the West.” By the start of the First World War, Winnipeg had the third-largest population in the country, and downtown development was booming.

“All roads lead to Winnipeg,” a reporter from Chicago wrote in 1911, in a passage later quoted by historian Alan Artibise. “It is the focal point of the three Transcontinental lines of Canada, and nobody, neither manufacturer, capitalist, farmer, mechanic, lawyer, doctor, merchant, priest, nor labourer, can pass from one part of Canada to another without going through Winnipeg. It is a gateway, through which all the commerce of the east and the west, and the north and the south must flow.”

Right at the heart of it all was the downtown.

But soon came reasons for worry, here and elsewhere. The Great Depression wrought havoc on local business and industry, a pang felt deeply in the bustling core. The end of the Second World War brought an economic boost and pent-up demand, but it was soon dampened by the great flood of 1950, Artibise wrote. Meanwhile, other cities in other provinces began to catch up, and an exodus took place and accelerated, with the population once concentrated in the city’s core moving outward. The economic activity spread beyond the downtown, into areas with lower costs, more parking, and in closer proximity to where workers were living. In 1968, a Free Press writer stated “the most important face that any city wears is downtown,” later surmising that Winnipeg’s downtown was “gradually, but definitely, dying.”

In the 1980s, recognizing a truth in that grim sentiment, the municipal, provincial, and federal governments joined forces on a program called the Core Area Initiative, injecting $96 million in spending into the physical renewal of the inner city and the downtown through housing, community infrastructure and large-scale projects.

“By then, the level of desperation had reached a point where an unprecedented effort was needed,” says Jino Distasio, a professor of geography and the director of the University of Winnipeg’s Institute of Urban Studies.

Those efforts continued: if anything is as persistent as rumours of the downtown’s impending ruin, it’s a stubborn optimism that its glory waits around the corner. In recent years, the dominoes that had been laid out for decades started to fall in quick succession.

In 2004, on the former site of the iconic Eaton’s building — a defining piece of the downtown’s history — a hockey arena opened its doors after the store was demolished, paving the way for the return of the NHL’s Winnipeg Jets less than a decade later. Other developments to follow included the opening of the Canadian Museum for Human Rights, the continual growth of The Forks Market, the growing footprint of the University of Winnipeg, the completion of True North Square, the construction of what’s soon to be the city’s tallest finished building at 300 Main St., and the establishment of Qaumajuq at the Winnipeg Art Gallery.

Of course, issues in the area, such as insufficient quality affordable housing and access to resources, persist, but from a growth perspective, Distasio says the 15-year period beginning in 2005 was similar to the boom at the beginning of the 20th century. “I thought the downtown was doing quite well,” he says.

With the pandemic’s arrival came a reminder of how quickly life can change, and that was true for the downtown, too. Development continued, but foot traffic decreased. An unknown proportion of an estimated (by the Downtown Winnipeg Business Improvement Zone) 70,000-80,000 downtown workers began working from home or lost their jobs. University students took classes online instead of downtown. The hockey arena was emptied of fans. At least 40 businesses have closed, by the Downtown BIZ’s count, while many others are a bad month or two away from the same fate.

According to real estate firm CBRE, the downtown office-vacancy rate is now 14 per cent, as compared with 11.6 per cent at the end of 2020. The historic Bay building closed, its windows boarded up, with calls for the creation of more affordable housing and adaptive reuse stapled to the plywood.

To varying degrees, every downtown across the country is struggling under the same pressures and changes, says Richard Shearmur, a professor at the McGill School of Urban Planning. With workers no longer congregating downtown and no major cultural events taking place, there’s been a domino effect, impacting the areas from an economic as well as symbolic perspective. “Until people can come back, downtowns will be struggling,” he says.

Pierre Filion, professor emeritus at the University of Waterloo’s School of Planning, agrees. “Economically, downtowns are the worst affected part of the metropolitan region during the pandemic,” he says.

Filion’s focus is on downtowns, and he says that, like Winnipeg, many cities experienced some of their best years prior to the pandemic, as the regions diversified with housing and entertainment options. “In a lot of cities, the last decade was the best decade downtown,” he says. “They were more active than they’d ever been.”

That’s perhaps why the lack of activity seems especially stark, as it does on the streets of downtown Winnipeg.

“It’s very quiet,” says Manfred Keil, who’s been a frequent visitor to downtown Winnipeg since he moved to the city 60 years ago, while standing on Graham Avenue. “There’s obviously not as much life right now,” he adds, right before boarding a mostly empty bus.

● ● ●

That there is less life downtown is one man’s opinion. What does the rest of the city and province think? The Free Press enlisted Probe Research to find out.

Last month, the pollsters asked a representative sampling of 1,000 adults in Manitoba several questions related to the downtown, gleaning from the answers a moment-in-time glimpse into the public perceptions of the historic area.

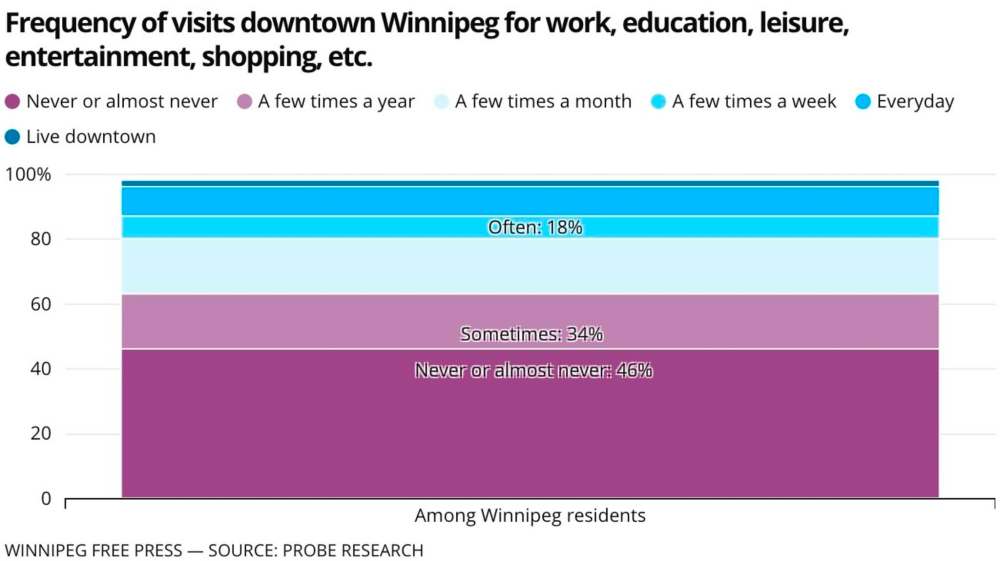

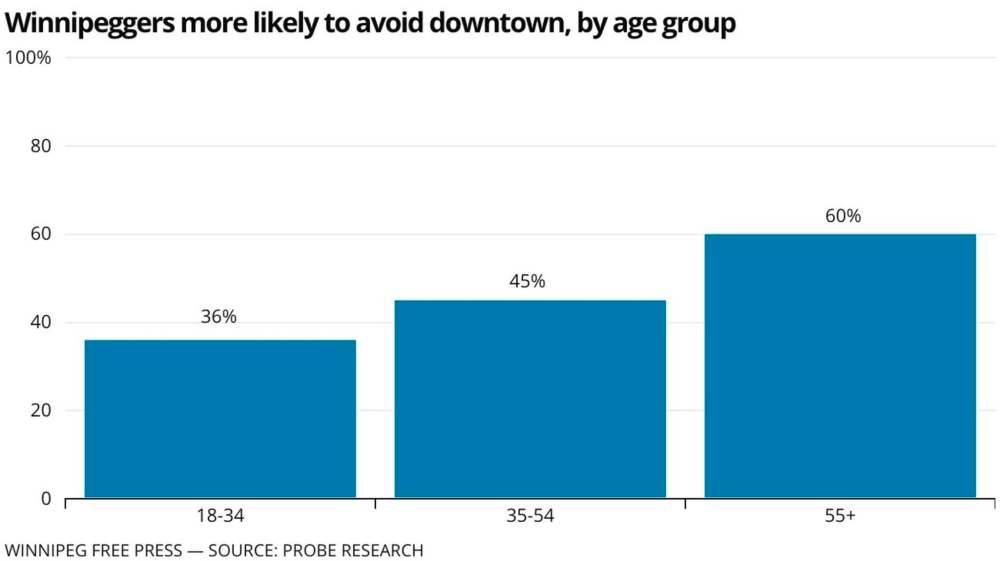

The data lend some credence to the views of the man on the street. Asked how often they visit the downtown during the pandemic, 46 per cent of Winnipeggers said “never or almost never.” The percentage is even higher for women (51 per cent) and those over the age of 55 (60 per cent). Only 18 per cent of Winnipeggers, of which two per cent live downtown, said they visit often.

Comparing that to the frequency of their visitation before the pandemic, 67 per cent of respondents said they were spending less time downtown, with 51 per cent saying they were spending “a lot less” time there. About three in four university graduates, people earning over $100,000 per year, parents with young children and residents of northeast Winnipeg said they were spending less time in the area, making them the most likely to not go there.

The data make sense, says Probe principal Mary Agnes Welch, but that doesn’t necessarily make the responses any less concerning. “This data really speaks to the precipice the downtown is on right now, and of course it’s largely pandemic-related,” she says. “But pretty much half of Winnipeggers never or rarely come downtown and, to me, that’s a pretty stark number.”

About the poll

Between March 10 and 26, Probe Research surveyed a random and representative sampling of 1,000 adults residing in Manitoba. They were asked the following three questions.

Between March 10 and 26, Probe Research surveyed a random and representative sampling of 1,000 adults residing in Manitoba. They were asked the following three questions.

Question 1: Thinking about your daily life right now, during the pandemic, how often would you say you visit downtown Winnipeg for work, education, leisure, entertainment, shopping, etc.?

Question 2: Compared to before the pandemic, are you currently spending more time downtown, same amount, or spending less time downtown?

Question 3: Please read the following statements and indicate if you agree or disagree: I’m worried about the future of downtown Winnipeg; governments should spend money to help downtown recovery from the pandemic; there’s not a lot that attracts me to downtown.

With the sample size, one can say with 95 per cent certainty that the results are within plus/minus 3.1 percentage points if the entire adult population of Manitoba had been surveyed.

Kate Fenske, the CEO of the Downtown BIZ, didn’t find the decrease in visitation at all surprising, given that the downtown as a destination doesn’t have the same draws — arts, sports, public events — it would normally enjoy. Even before the pandemic, to hear only half of Winnipeggers come downtown frequently wouldn’t have been very surprising either. She sees the figure another way: 50 per cent of Winnipeggers do visit, even if it might be once or twice a year. Plus, while 40 businesses downtown have closed, 21 new ones have opened. Many of the existing outdoor public places are being used and enjoyed by Winnipeggers more than ever during the pandemic.

But to say this moment is filled with optimism would be an overstatement. Probe also polled respondents on their attitudes about the downtown’s recovery, with 72 per cent saying they were worried about the area’s future (29 per cent strongly agreeing, 43 per cent somewhat). Almost two-thirds agreed with the statement, “There’s not a lot that attracts me to downtown Winnipeg” (29 per cent strongly, 36 per cent somewhat).

Those proportions are heavily influenced by the pandemic. The Downtown BIZ’s own survey questions through Probe shed a slightly different light on the situation. More than half of downtown workers have no concerns about returning to work/working downtown. Of the 43 per cent that do have concerns, they’re mainly in the areas of safety, transportation and parking. (Meanwhile, only 20 per cent of downtown workers have returned full-time, polling showed.)

That, says Fenske, shows there’s plenty of work to be done if the downtown has hopes of getting back to where it was, or better, advancing past its pre-pandemic standard.

That means addressing long-standing issues head on: diversifying and increasing the residential population, investing in freely accessible public spaces such as parks and other greenspace, and complete streets, designed to encourage pedestrians, cyclists and drivers alike to safely and easily traverse the neighbourhood — values that have received an unprecedented boost from the pandemic. “We need to get back, but we’ll need to ask how we can do things better and differently than before,” she says, echoing the questions all downtowns are facing.

McGill’s Shearmur says every downtown is suffering and likely will for the short to medium term. “What needs to happen now is to develop a good plan for when COVID is over, though we don’t know when that will be,” he says.

With solid planning and pent-up demand, he believes there’s the possibility for a new Roaring ‘20s; it’s common throughout history for periods of exuberance to happen following major tragedy or national upheaval. “At this point, though, it’s about tightening belts.”

Filion, who is working on a book about Canadian downtowns, says part of the future plans should focus on continued diversification efforts, with the regions becoming less work-oriented and more oriented to public activity. “There is going to be bounceback, but to what extent? That’s not certain. And will it be necessary to have interventions to make it so?”

Some action will likely need to come through government support, an idea popular among respondents, according to the Free Press-Probe polling. One-quarter strongly agreed and 45 per cent somewhat agreed that governments should spend money to help the downtown recover from the pandemic.

“I think if you’re the government, you see there’s significant support in some intervention,” Welch says. “But you also perhaps see the downtown has an innate structural problem in that half of the people don’t go there.”

“I think it’s going to be an uphill battle,” says Fenske, referring to getting the downtown back to business.

There are a few major decisions ahead, aside from the pandemic, that will have enormous implications on how the battle turns out. One is the future of the now-closed, historically protected, downtown Bay building, a 650,000-square-foot behemoth that faces an unclear future with myriad possibilities for reuse and rejuvenation. On Wednesday, the Pallister government announced in its provincial budget the establishment of a $25-million trust fund to help redevelop the building.

Another decision is related to the Portage Place shopping mall, mired in delays as Starlight Investments, the company that bought it in 2019, seeks nearly $300 million in federal grants and loans to redevelop it into a mixed-use housing and commercial project; the city and province have earmarked $20 million and $28.7 million, respectively. Winnipeg Centre MP Leah Gazan opposes the Starlight plan and private ownership of the mall, arguing that it should be publicly owned, as it is a public good.

The city’s most important face could look very different depending on how those scenarios — and the current destructive powers of the pandemic — play out.

• • •

The cashier’s Tuesday has been a quiet one. A few people walk in to buy soft drinks, others seek change for a five.

“It’s been very hard, very slow,” he says. But the weather is getting warmer, the snow is gone, and as the weeks pass and the vaccine rolls out slowly but surely, more people seem to be standing on Graham Avenue. “We will survive.”

He hopes his daily and hourly counts will increase. Maybe by the end of the year, the missing faces will start to reappear. Maybe work will feel a little less lonely.

At about 3 p.m., he stands up to stretch a little, turning toward the window. “This is the best time,” he says.

Slowly, people trickle toward the bus stop. He’s happy to see them, even if they don’t come through the door.

ben.waldman@freepress.mb.ca

Ben Waldman is a National Newspaper Award-nominated reporter on the Arts & Life desk at the Free Press. Born and raised in Winnipeg, Ben completed three internships with the Free Press while earning his degree at Ryerson University’s (now Toronto Metropolitan University’s) School of Journalism before joining the newsroom full-time in 2019. Read more about Ben.

Every piece of reporting Ben produces is reviewed by an editing team before it is posted online or published in print — part of the Free Press‘s tradition, since 1872, of producing reliable independent journalism. Read more about Free Press’s history and mandate, and learn how our newsroom operates.

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.