First Black Jets player faced tough path Bill Riley target of taunts, threats

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$1 per week for 24 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $4.00 plus GST every four weeks. After 24 weeks, price increases to the regular rate of $19.95 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.99/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19.95 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 26/02/2021 (1839 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

Much as he’d like to forget it, much as he wished it had never happened or that he’d handled it differently, the memory is burned into Bill Riley’s brain.

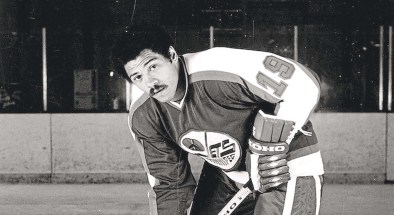

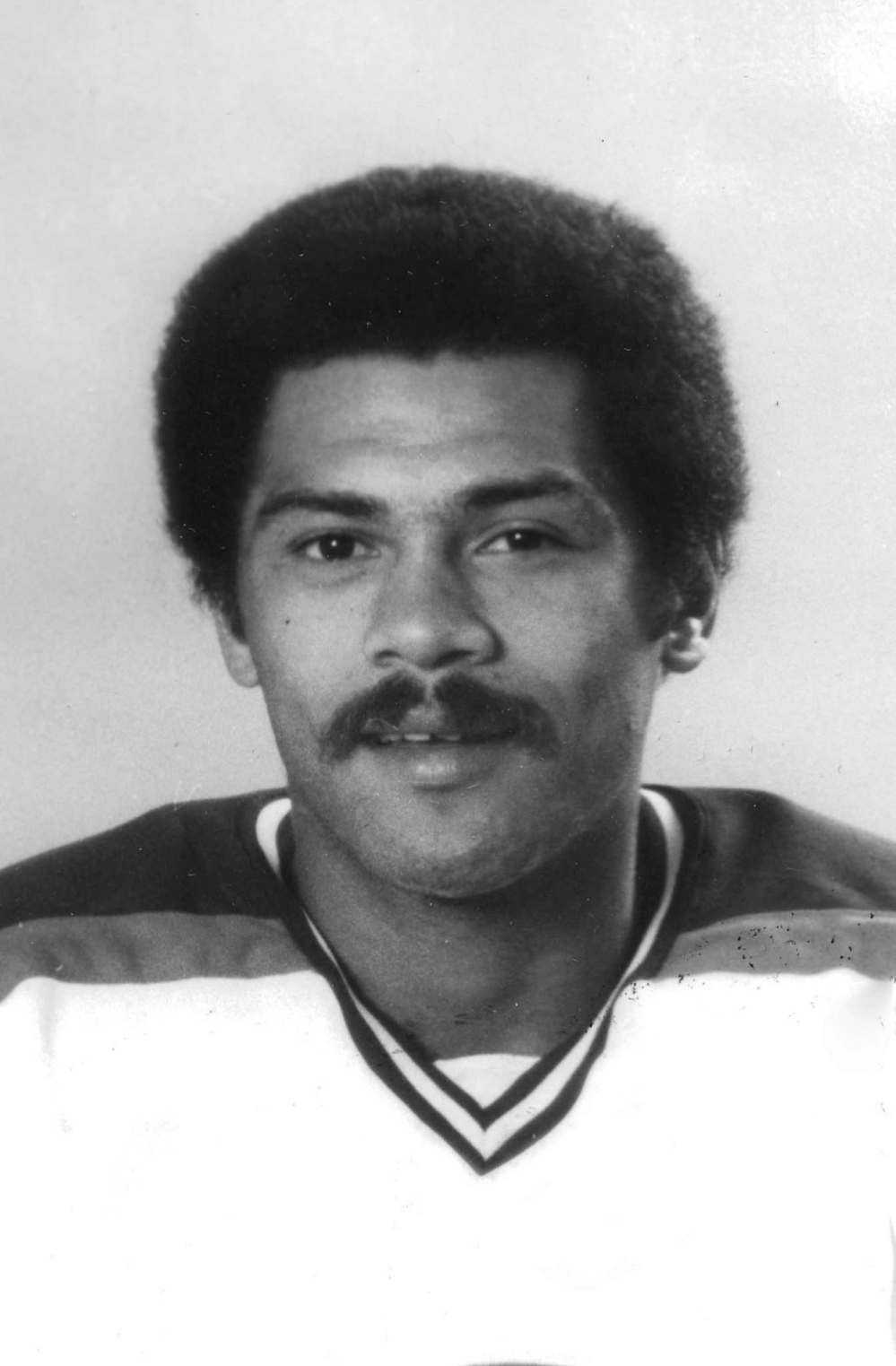

The first Black player for the Winnipeg Jets — a "cup of coffee" is how he describes his 14-game stint during the 1979-80 season — was often the target of racist taunts as he worked his way up to the big leagues.

One night in particular stands out, a game in the mid-1970s where his Dayton Gems were visiting Kalamazoo of the International Hockey League. Riley, a tough but high-scoring forward from Amherst, N.S., was shocked by the scene that awaited him as he hit the ice.

"They’d hung a big black ape (stuffed animal) with my sweater on it. They had lynched it, with a hangman’s knot around the throat of the gorilla," the now 70-year-old Riley recalls, his voice cracking with emotion.

Riley was just the third Black player to make the NHL, following in the footsteps of Fredericton’s Willie O’Ree, who played 45 games with Boston over two seasons starting in 1957. Mike Marson, of Scarborough, was the second, skating in 196 NHL games between 1974 and 1980 with Washington and Los Angeles. Marson and Riley were teammates at one point with the Capitals.

Like so much of what he endured in that era, Riley believed he had to stay silent if he wanted to stick around. The numbers, he said, were not in his favour. Not in that rink, and certainly not in the sport.

“They’d hung a big black ape (stuffed animal) with my sweater on it. They had lynched it, with a hangman’s knot around the throat of the gorilla.” – Bill Riley on a game in the mid-1970s in Kalamazoo

"I didn’t want to be perceived as a problem, because people have a way of turning things around, saying ‘Hey, this guy is gonna cause a problem, stay away from him,’" Riley explained. "I didn’t want to say nothing, because I didn’t want to shut the doors for all the young Black players coming up. So I bit the bullet."

It was the much same during repeated visits to Toledo, where five-cent beer nights meant the crowd, mostly young white males, were going to be extra vocal. And, at times, extra racist.

"They’d get all slopped on the beer, and I’d go in there and knew I was in for a long night. A tough night," said Riley. He rattled off other off-ice examples as well, including having to get white teammates to rent him places to live because landlords wouldn’t have dealt with a person of colour.

"Sometimes, now, I get upset at myself for not saying more. Then i turn the television on and see guys like Ryan Reaves and Wayne Simmonds and all these guys and think, geez, you paid the ultimate price for these guys," said Riley.

Jermaine Loewen has never met Bill Riley. But he’d love to one day shake the hand of a man who helped pave the way for athletes like him to make a living in the sport.

The 23-year-old from Arborg is currently playing for the Henderson Silver Knights, the farm club of the Vegas Golden Knights. He is one of 90 current BIPOC (Black, Indigenous and people of colour) players at either the NHL or AHL level. That includes multiple Manitobans including Ryan Reaves and Keegan Kolesar of the Golden Knights, and Madison Bowey of the Chicago Blackhawks.

"You realize what people who came before you went through," said Loewen. "It’s fantastic to see so many from Manitoba. The more people who see others who look like them playing, the more people will want to watch and start playing hockey. I think it’s moving in the right direction."

Loewen certainly didn’t see anybody lacing up the skates in Jamaica, where he was born in 1998. But an incredible series of events have now led to him becoming the first-ever NHL drafted player from the island country.

Loewen’s birth parents abandoned him at an orphanage at the age of one, and he’d spend the next two years in care. Along came Stan and Tara Loewen of Arborg who were visiting Jamaica while doing Christian ministry work and happened to see Jermaine’s photo in an advertisement. It was love at first sight.

Loewen, along with sister Makeda, 14, and brother Nathaneal, 12, were adopted by the couple and brought to Canada, a move he calls "lifesaving."

"I went from one of the warmest places in the world to one of the coldest," Loewen jokes.

“Our mantra is that inclusion is year-round. We need to begin to normalize all of these faces in our spaces in hockey. This is not a one and done. This is an attempt to continue to get people to see black and brown and female faces as normalized in our sport. That work is going to continue.” – Kim Davis

Ah yes, but they have plenty of ice around here, and Loewen had a natural athletic ability which quickly emerged as he worked his way up through the amateur ranks in the Interlake, eventually resulting in a four-year stint with the Kamloops Blazers of the Western Hockey League, in which he was named team captain.

The Dallas Stars drafted him late in the seventh round, 199th overall, in 2018, but didn’t ultimately sign him. Vegas then grabbed his rights. To date Loewen has one goal and one assist in 36 AHL games, and three goals and one assists in 19 games with Fort Wayne of the ECHL.

None of it was easy, and Loewen said he bristled at how often he’d be referred as simply "the Black kid", whether it was during a hockey game or at school.

"It was more ignorance than anything," he said. "Some people have definitely had it worse. I’m pretty grateful I didn’t get it too bad. But it’s hard, because you know there are people who are going to say things just to try to get under your skin."

Ray Neufeld doesn’t think of himself as a trailblazer. But there’s no question that as the first Black pro hockey player from Manitoba, the Winkler product broke some barriers.

"When I started there were like just four or five of us playing. Today, there’s so many more. They need to be given a safe environment so they don’t feel disrespected or discriminated against," said Neufeld, who skated in 595 NHL games including 259 with the Jets from 1985 to 1989. "It’s impressive, and very positive, how many there are now."

Neufeld, now 61, speaks highly of his time spent playing in his home province, saying he never felt the colour of his skin was an issue. From other former Jets such as Eldon "Pokey" Reddick to more recent stars like Evander Kane and Dustin Byfuglien, to current prospect and Manitoba Moose player C.J. Suess, this city has been home to many BIPOC players over the years.

"There was probably the odd thing said here and there but overall people were really great. It helps, I think, that Manitoba has just about every culture you can imagine. It’s kind of unique," he said. "But there’s no question some crazy things happened back then (in the sport). There were lots of things that happened to people that shouldn’t."

There was one AHL game in the late 1980s, played in Sherbrooke, where Neufeld and a Black teammate, Graeme Townshend, were subjected to a fan making monkey sounds from the stands.

Neufeld said people like O’Ree, Marson and Riley were the pioneers he looked up, and he’s glad today’s generation has many more to serve as inspiration.

"Nothing happens quickly, and it’s hard to know how that will play over time. I think over time you’ll continue to see an increase in the BIPOC area of hockey, but to what level I don’t know," he said.

Neufeld has continued to work with the NHL on matters of inclusion, including some recent virtual panels.

"Willie and Bill and Mike and what they endured… someone else had walked that road before we could. You can always learn from history. You can’t change it, but you can learn a lot from it," he said.

"I think sports in general, but certainly hockey, has made some great strides in that area."

The 85-year-old O’Ree has become the face of the NHL’s recent Black History Month campaign — players have worn tribute skates to him over the past month, and his No. 22 jersey is set to be retired by the Bruins next season in a ceremony pushed back until fans can be in the building.

Riley said he and Marson have yet to hear from the league.

"We’ve got stories to tell. We can help. Willie can’t cover all that ground by himself. Willie was the first, and and nobody can ever take that from him. But there’s a lot of kids out there, a lot of ground to cover. It’s frustrating," said Riley, who would like to write a book one day about his experiences in the hockey world.

Although his time coming up through the minors was difficult and downright ugly at times, Riley enjoyed his brief time in Winnipeg but wishes it could have lasted longer. He scored three times and had two assists in his 14 games with the Jets before being sent to their AHL affiliate in Nova Scotia. He never got back to the NHL, despite being nearly a point-per-game player in the minors for five more years before retiring.

The Jets had just drafted Jimmy Mann 19th overall, and Riley believes general manager John Ferguson wanted to clear out room for a younger player who would play a similar role with the franchise. His final NHL resume involves 139 games (he played for Washington before coming to Winnipeg) with 31 goals, 30 assists and 320 penalty minutes.

"There was a lot of politics involved, for sure. I would like to believe it was politically motivated as I know Tommy McVie (then the Jets coach) went to bat for me," said Riley, who doesn’t believe race played a factor.

"I knew that I was playing well, I had no problem dropping my gloves in defence of my teammates, and I was very good in both ends of the rink. That still wasn’t enough."

Riley is happy to see the league moving in the right direction when it comes to issues of racial diversity and inclusion, but he’s holding his applause at this point.

"When (the George Floyd killing and protests) started happening last summer, I kept waiting and waiting, wondering where was the NHL. I saw the NBA, I saw Major League Baseball, I saw the NFL. But the NHL, they were making themselves look like a bunch of rednecks," said Riley.

"The NHL was the last sport to step up to the plate of the Black Lives Matter movement. And it took the players in order for that to happen."

Loewen said his current hockey environment in the desert is a diverse one. Former NHLer Joel Ward is an assistant coach with the Silver Knights, while former Manitoba Moose netminder Fred Brathwaite is the goalie coach with the club.

Regardless of where his career ultimately takes him — playing in the NHL is the ultimate dream, of course — he’s already a winner. And that was cemented a few months ago when he co-authored a children’s book called Ari’s Awful Day/Mainer’s Move. It was the brainchild of his agent, Ray Petkau, the product of Steinbach who has a wealth of big-league clients including Jets goaltenders Connor Hellebuyck and Laurent Brossoit.

Mainer is based on Loewen, a black bear who moves to a new city and joins a hockey team which includes Ari, a lion, who doesn’t immediately accept him. The story, which Loewen penned along with co-author and illustrator Thom van Dycke, follows their paths as these polar opposites work towards an eventual friendship. Themes of kindness, acceptance and racial inclusivity are tenderly portrayed.

Loewen is looking forward to doing some readings, both online and eventually in classrooms, to spread the message.

"I think the world needs a lot more of that. Especially with what’s happened over the last year, for a number of reasons," said Loewen. "Hopefully the young kids can see that no matter where you come from, or what your race, that if you put in the work you can make it.

Honouring the past. Highlighting and recognizing the current. Amplifying the future. That was the goal of the NHL this year for Black History Month, which officially concludes on Sunday following a full slate of mostly virtual seminars and educational summits. But the work is really just beginning.

"You can’t know where you’re going if you don’t know where you’ve been," said Kim Davis, Senior Executive Vice President of Social Impact, Growth Initiatives & Legislative Affairs.

"Our mantra is that inclusion is year-round. We need to begin to normalize all of these faces in our spaces in hockey. This is not a one and done. This is an attempt to continue to get people to see black and brown and female faces as normalized in our sport. That work is going to continue."

Davis singled out a couple Manitobans for personal praise. Loewen, she said, is a terrific modern-day example for young kids to follow, and his work as an author will make huge strides in that area.

"It just makes us even more focused on ensuring that we remove any of the barriers that exist for kids of colour. It’s an inspiration, for him to use his creativity to do the book was great. That kind of storytelling is what creates empathy in parents and allows them to have the kind of language they need to talk about these issues to their kids," she said.

And then there’s the important work of Reaves, who led the way last summer in the Edmonton bubble following the killing of Floyd, a Black man, at the hands of Minnesota police. The image of Reaves standing front and centre, backed by dozens of other mostly white players, to denounce the latest act of racialized brutality and pause the playoffs for a couple days was extremely powerful,

"He has brought such an amazing voice to our thinking about the future to bringing more diversity and inclusion," said Davis.

"For him to get his fellow white players to stand up and use their voices, that’s what’s going to make a difference in our sport. We know that 95 per cent of our players are white, so allyship is going to be the way in which we change our sport. I see that happening and it’s exciting."

Davis said Manitoba should be proud to have so many BIPOC players in the pro hockey ranks and points to the Winnipeg Jets Hockey Academy, run by the True North Youth Foundation, as serving a vital role. One such example is the story of the Nnah family, which immigrated from Africa eight years ago. Now the three boys — Anointing, Winner and Divine — are regular rink rats thanks to the opportunities that were afforded them.

"There’s just an amazing amount of support happening in the province, and specifically in Winnipeg," said Davis. "When we start seeing the pipeline have positive trends over time and more kids of colour feeling like this sport belongs to them, I think we’re going to see the kind of growth we want. We’re making improvements, we know we have a lot of work to do, but we’re really starting to feel the winds of change blowing in the right direction."

"This is a movement, not a moment."

mike.mcintyre@freepress.mb.ca

Twitter: @mikemcintyrewpg

Mike McIntyre is a sports reporter whose primary role is covering the Winnipeg Jets. After graduating from the Creative Communications program at Red River College in 1995, he spent two years gaining experience at the Winnipeg Sun before joining the Free Press in 1997, where he served on the crime and justice beat until 2016. Read more about Mike.

Every piece of reporting Mike produces is reviewed by an editing team before it is posted online or published in print — part of the Free Press‘s tradition, since 1872, of producing reliable independent journalism. Read more about Free Press’s history and mandate, and learn how our newsroom operates.

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.