A lover of language

Born in a blizzard and unbowed by her residential school misery, beloved elder Doris Pratt's passion for language and love of learning fuelled commitment to her Dakota Nation

Advertisement

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$1 per week for 24 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $4.00 plus GST every four weeks. After 24 weeks, price increases to the regular rate of $19.95 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.99/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19.95 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 09/11/2019 (2317 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

If her early education taught her anything, it was exactly how not to be a teacher.

She once awoke to a strapping from an instructor. Another time a teacher called her “Indian trash.”

But Doris Pratt’s life wasn’t defined by her residential school scars.

It was defined by the Dakota dictionaries she published. The teachings she gave in her mother tongue. And an ever-present dedication to both her students and dialect revitalization.

● ● ●

Pratt was born the youngest of nine children on Feb. 10, 1936, during a blizzard on what was then known as Oak River Reserve, located about 50 kilometres west of Brandon. The community is now known as Sioux Valley Dakota Nation.

Her parents, Demas and Bessie Dowan, thought their newborn would die because the midwife did not arrive due to the storm.

Little did they know their daughter would brave the storm to become a highly educated and highly respected Dakota matriarch in their community, in other First Nations and across the country.

“She always saw such an importance to maintain the language, and what comes with the language is the culture,” said Evelyn Pratt, one of her seven children.

Throughout her lifetime, Pratt was known as Duzahan Mani Win (Walks Fast Woman). She died of complications related to diabetes on March 6 at the Dakota Oyate Lodge personal care home. She was 83.

As Pratt noted in a draft of her soon-to-be-published autobiography (she had nearly finished it when she died), her earliest memories include learning Dakota and, later, English from her older siblings who returned home from residential school over the holidays.

At age six, she was already bilingual. It was no surprise then that she was called upon to be a translator by her teacher at missionary day school. She was asked to tell her classmates — in Dakota — when it was lunchtime and the like.

“That didn’t go over well with the other classmates,” Evelyn said. “It was like she was being favoured, so then she was bullied.”

There were bullies at Elkhorn Residential School, too. Those bullies were much older, racist and violent. But Evelyn said her mother wasn’t bitter about her upbringing. Rather, she said, “she just tried to make the best of her time.”

She and her friends traded only whispers in Dakota when the teachers were out of hearing range. Pratt spoke Dakota openly again after she finished grade school and returned home to take up work as a maid, gardener and homemaker before she enrolled in university in her mid-30s.

Gail Flett, a close friend who met Pratt through the Assembly of Manitoba Chiefs (which Pratt co-founded), said she “loved to learn.”

Pratt earned a bachelor of teaching, bachelor of education and a master’s of education from Brandon University. She also completed an educational specialist degree from the University of Arizona.

“The fact she was told that she was not smart enough, not good enough, made her determined to make children understand that anybody can learn — that if you apply yourself and you’re given the right tools, you’re given the right guidance and encouragement, any child can succeed,” Flett said.

It was around the time Pratt began her post-secondary pursuits that she became particularly fascinated with language revitalization. So much so, she began a solo project. She would create a phonetic writing system for Dakota that allowed children and adults to read and write their language.

The structure mimicked how students already learned English in school. For that, she was both applauded and criticized for using a colonial skeleton. Her work, however, would win numerous awards.

Like many Indigenous languages, historically, Dakota is an oral dialect. It has become critically endangered.

There are 1,760 people who have some knowledge of the Dakota language in Canada; 760 of them live in Manitoba.

Flett said her friend became “the top federal translator for Dakota.”

Pratt taught as an elder, teacher, special education instructor, principal, university administrator, curriculum adviser and professor. She co-ordinated the Brandon University northern education program in Winnipeg and gave lectures on the Dakota language at Brandon University.

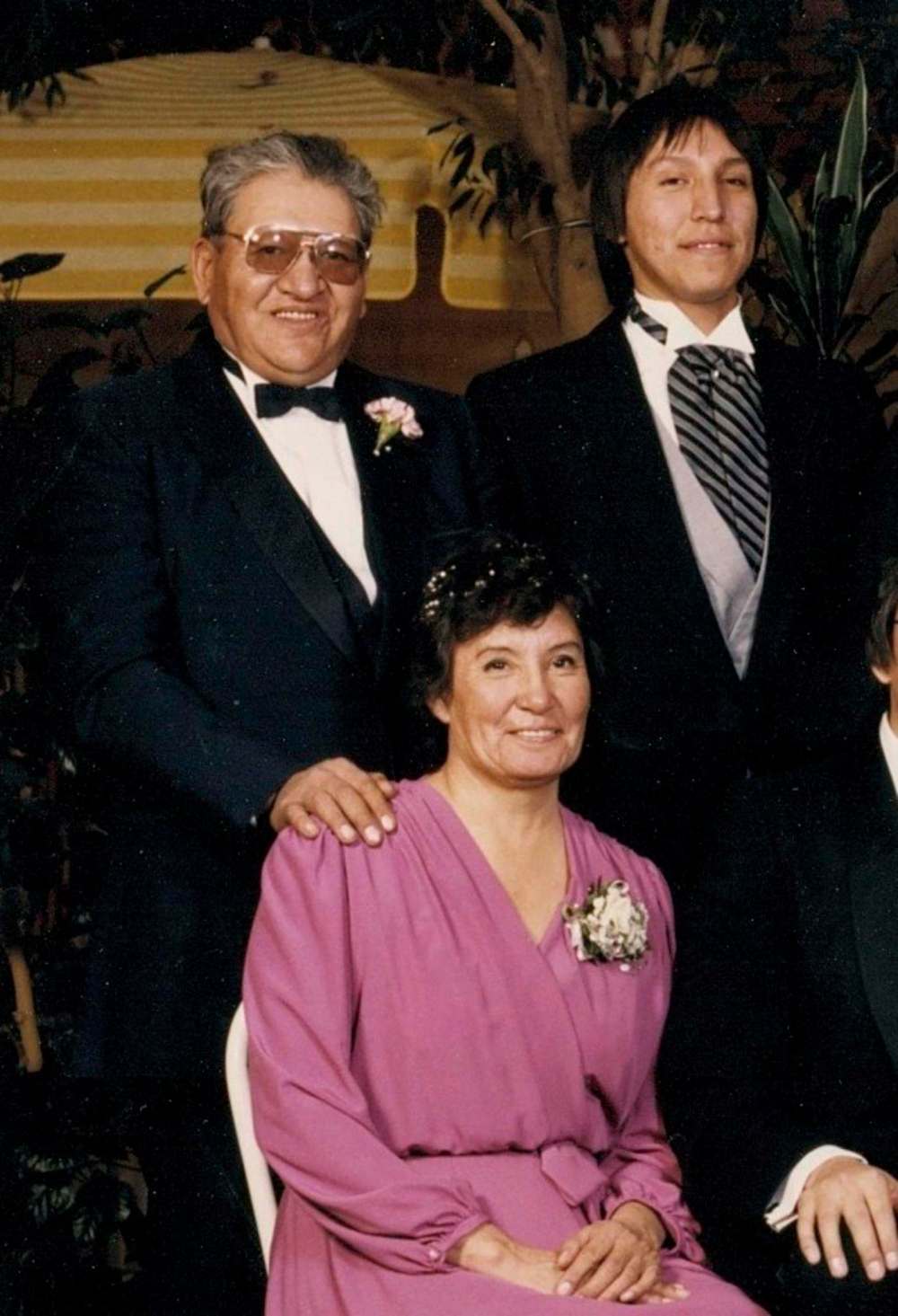

At home, she laid the groundwork for Sioux Valley Dakota Nation’s education system. A family woman who died a grandmother to dozens, she was able to dedicate much time to language revitalization with help from her supportive husband, Walter Pratt.

“She was considered an ambassador to her Dakota Nation in the area of education. She carried that very well and very proudly,” said Kevin Nabess, Sioux Valley’s director of education. The two worked together for the last 10 years of Pratt’s life.

Nabess describes Pratt as a professional educator who held high standards for all those she worked with. “She expected all educators to promote hard work ethic, professionalism and a true caring for the students that they served,” he said.

Both the physical curriculum and “hidden curriculum” mattered to her. She encouraged educators to be role models in their daily behaviour.

When she taught, Wakan Tanka (“great spirit”) was a common phrase she used; she believed spirituality guided the lives of all humans. “She was a prayer warrior,” Evelyn said.

Pratt was honoured with a long list of awards for her work, although she didn’t think she deserved the honours, something Evelyn said was a result of the abuse her mother endured as a child.

Friends and family point to Pratt’s YWCA Brandon Women of Distinction Award as one she was especially proud of; she was honoured for her lifetime of achievements at a ceremony in 2015.

Her acceptance speech?

“Not bad for ‘Indian trash,’ eh?”

maggie.macintosh@freepress.mb.ca

Twitter: @macintoshmaggie

Maggie Macintosh

Education reporter

Maggie Macintosh reports on education for the Free Press. Originally from Hamilton, Ont., she first reported for the Free Press in 2017. Read more about Maggie.

Funding for the Free Press education reporter comes from the Government of Canada through the Local Journalism Initiative.

Every piece of reporting Maggie produces is reviewed by an editing team before it is posted online or published in print — part of the Free Press‘s tradition, since 1872, of producing reliable independent journalism. Read more about Free Press’s history and mandate, and learn how our newsroom operates.

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.

History

Updated on Saturday, November 9, 2019 8:48 AM CST: Tweaks headline.

Updated on Saturday, November 9, 2019 11:30 AM CST: Corrects "nuns" to teachers: She and her friends traded only whispers in Dakota when the teachers were out of hearing range.