Dyed in the wool legacy

Former crafts guild president's passion for natural colours, fibres was 'fabricated into her life'

Advertisement

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$1 per week for 24 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $4.00 plus GST every four weeks. After 24 weeks, price increases to the regular rate of $19.95 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.99/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19.95 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 01/06/2019 (2478 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

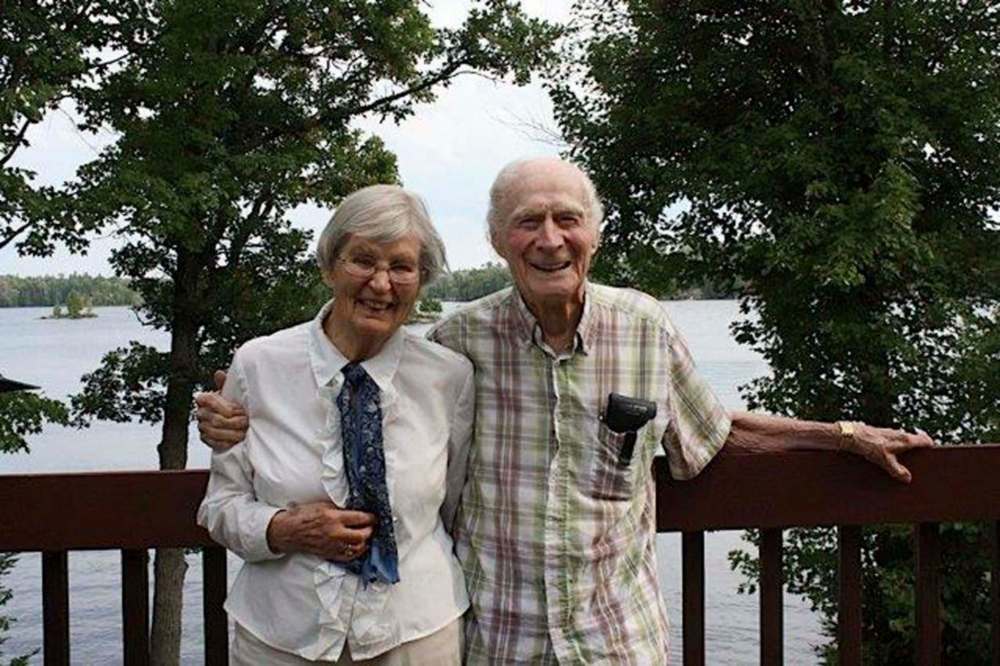

Margaret Ferguson wove her love of nature into her life.

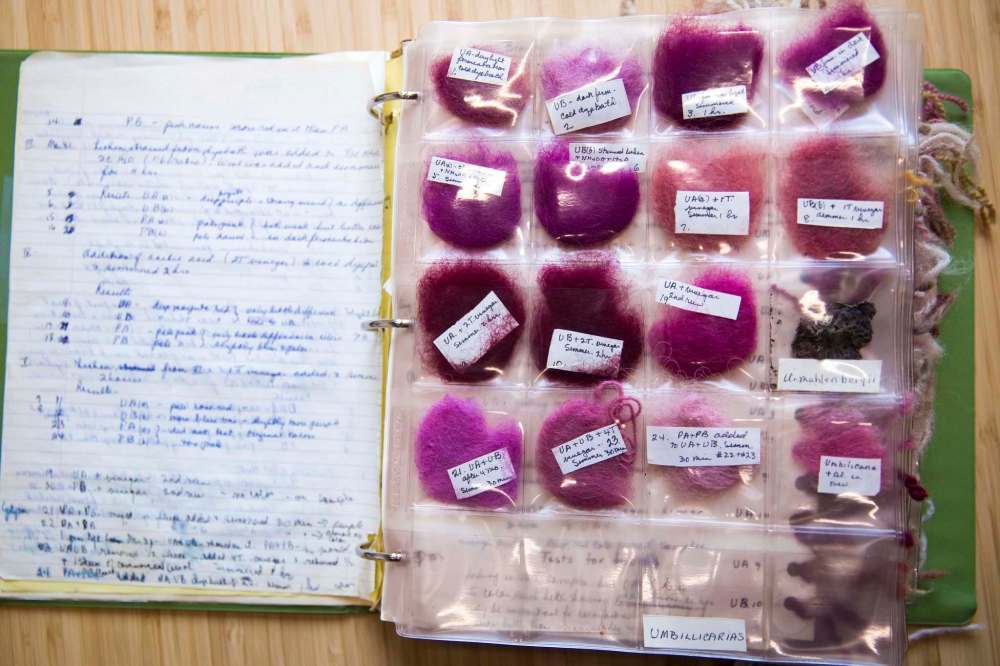

The Winnipegger, who died on April 27 at age 97, left a legacy of lichen-dyed, homespun and woven tapestries cherished by her children and grandchildren — as well as her research notes at the Manitoba Crafts Museum and Library. The notes detail the colours created from lichen gathered during summers at her beloved Lake of the Woods.

“She had pots going on the stove in the cottage filled with dye,” said Lyn Ferguson, the eldest of three children.

Ferguson made her own dye, spun her own wool and wove beautiful, practical pieces, her daughter said. “It was kind of fabricated into her life.”

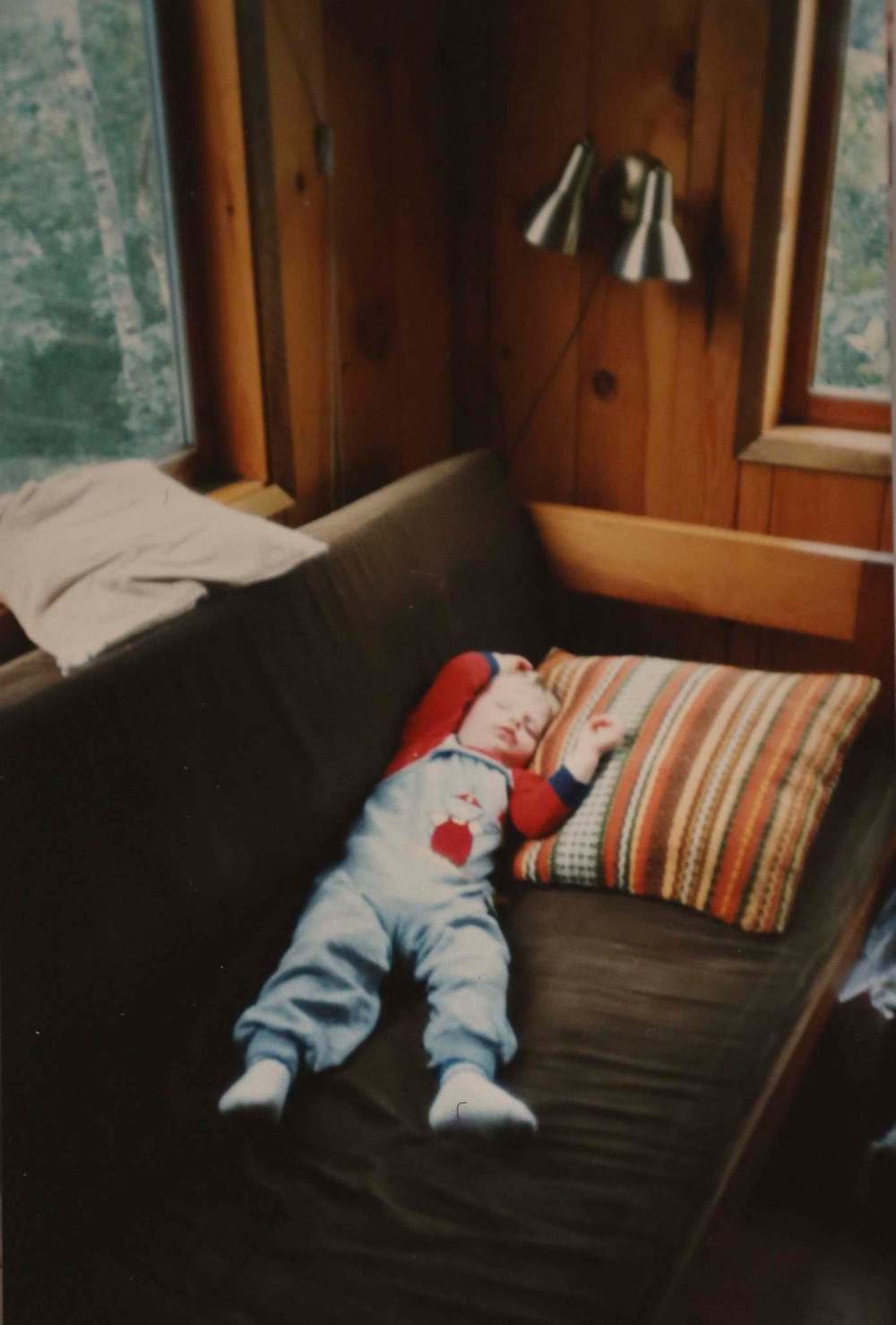

Going through family photos, the handiwork is omnipresent. “There’s her woven pillows, her rugs on the floor, a baby asleep on a handmade pillow. I have a beautiful scarf — she spun the wool, she dyed it, she wove it.”

The crafter and creator, who had a master’s degree in home economics specializing in foods and nutrition, used lichen as well as onion skins to develop richly hued dyes.

The Edmonton-raised Ferguson, and her University of Manitoba geologist husband Bob, had a cottage on Big Duck Island and a small aluminum boat.

They used it to buzz around and collect samples of the simple, slow-growing plant that typically forms a low, crusty, leaf-like or branching growth on rocks, walls, and trees.

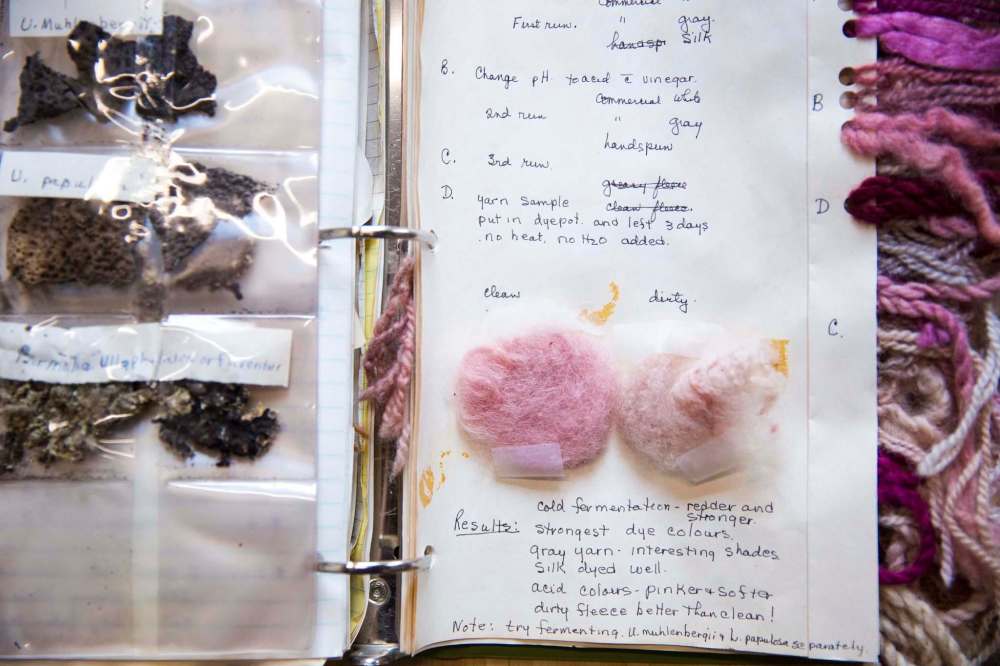

Her meticulous notes, drawings and dyed wool samples can be seen at the Winnipeg crafts museum and online in a Virtual Museum of Canada exhibit: Narrative Threads: Crafting the Canadian Quilt.

Her work at the crafts museum is part of an exhibit called Women of the Crafts Guild of Manitoba — a group Ferguson had served as president.

“It’s such a wonderful piece to show the research she did, in terms of doing the dyeing — and she used that for teaching,” said curator Andrea Reichert.

“She had people out to the cottage for dyeing workshops. She would make dye with all these natural materials and, from drab green and grey lichens, you could get hot pink and some super cool colours,” said Reichert.

“It was wonderful,” said Gerdine Strong, who took dyeing classes at the Lake of the Woods in the 1970s.

“It was very peaceful and they were so generous with having the craft people there,” said Strong, 87.

“The dark brown one gives you a gorgeous fuschia colour if you soak them in — the original recipe calls for strong male urine — but ammonia is what’s normally used,” she said with a laugh.

Strong and Ferguson belonged to a “cottage spinners group” that met monthly.

“She was a great one — very down to earth,” said Strong, who took over as the crafts guild president after Ferguson’s term ended.

The guild’s doors closed in 1997. Started as a branch of the Canadian Handicraft Guild, the provincial group’s goal was to generate money, help solve rural problems and preserve the art of craft-making — all rooted in feminism.

“It was such a huge organization, and for so long it was run exclusively by women,” Reichert said.

For Ferguson, an ardent feminist, it was a good fit.

“Crafts are very practical,” said her daughter Lyn. “She made beautiful things but they were always functional.”

Ferguson, known to her family as “Muzz,” had more than one spinning wheel, and a passion for wool.

“She collected wool,” said Lyn, who recalled her mom spinning dog hair. “But she was really fascinated with sheep.”

During a family trip to New Zealand, “she knew the names of all the sheep.”

Ferguson belonged to the First Unitarian Universalist Church of Winnipeg, and advocated for a safe environment and peace.

“She went through a stage where she was very concerned about radioactivity,” said her daughter, who recalled having to drink powdered skim milk that was thought to be safer.

“I still cannot, to this day, drink skim milk,” she said with a laugh.

The Fergusons opposed the Vietnam War — “I remember we hosted some draft dodgers in the ’70s” — and were progressive, open-minded and always learning.

“My parents were kind of young at heart, in many ways.”

When Bob took three research leaves (Cambridge and Oxford in England, and Adelaide, Australia) Ferguson went with him and embraced the opportunity.

It was during their time in Oxford in the early 1970s that Ferguson’s creative side began to flourish, her daughter said.

“When she got back, she became more interested in weaving and spinning.”

Then, she began experimenting with natural dyes at Lake of the Woods.

“The cottage was a magical place, as cottages often are, where the kids and grandkids and the cousins all came together,” said Lyn. “It was a place of great, great joy.”

Ferguson’s creativity wasn’t limited to textiles: her drawing of a huge pine tree near the cottage became an iconic image for the family. “Our son had it tattooed on his back,” said Lyn, who has a framed print hanging in her home.

The couple spent five months a year at their island cottage, and continued to go after Ferguson was diagnosed with vascular dementia at age 80. Bob helped care for her as long as he could. He died in 2015.

In her final years, Ferguson had no memory of her craftwork and dyeing, so she didn’t miss it, her daughter said.

“She wasn’t doing a lot of grieving,” said Lyn. “She was gracious, warm and lovely.”

A memorial service will be held July 8 at 2 p.m., at the First Unitarian Universalist Church of Winnipeg.

carol.sanders@freepress.mb.ca

Carol Sanders

Legislature reporter

Carol Sanders is a reporter at the Free Press legislature bureau. The former general assignment reporter and copy editor joined the paper in 1997. Read more about Carol.

Every piece of reporting Carol produces is reviewed by an editing team before it is posted online or published in print — part of the Free Press‘s tradition, since 1872, of producing reliable independent journalism. Read more about Free Press’s history and mandate, and learn how our newsroom operates.

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.