Building connections amid meth’s devastation Higher numbers of women, girls seeking treatment for methamphetamine use

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$1 per week for 24 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $4.00 plus GST every four weeks. After 24 weeks, price increases to the regular rate of $19.95 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.99/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19.95 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 19/12/2018 (2642 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

When she couldn’t walk to the bathroom without shoes on, “without being scared to step on a needle,” Ramona Harper decided to move out of her house.

The 16-year-old’s parents are both addicted to methamphetamine, and now she doesn’t know where they are.

“It’s sad to say that I’ve seen my own parents go from alcoholics to crack addicts, to getting clean on the reserve for two years, to coming right back to the city and starting where they left off, with a new drug,” she says quietly.

“It was a mess, really. Living like that, it really opens your eyes. I mean it when I say our people need help.”

As meth addiction takes hold across all demographics in Winnipeg, the drug is doing disproportionate damage to women and youth, who are more likely to be exploited alongside their addictions but have access to fewer treatment options.

Addictions workers say root causes of substance abuse can usually be traced back to past trauma, particularly for Indigenous people, and connections to the child-welfare system can’t be ignored. Even those, like Ramona, who don’t use meth themselves, are losing family and friends to a drug that’s become the norm.

Higher numbers of women and girls are seeking treatment for meth use, according to data from the Addictions Foundation of Manitoba. A rehabilitation counsellor says 60 per cent of her female youth probation clients had used meth, compared to 20 per cent of male youth clients.

In a report released last week, the Manitoba Child and Youth Advocate called attention to increasing rates of meth use among hundreds of sexually exploited youth and underscored the need for urgent, long-term treatment and a provincial strategy that tackles youth mental-health and substance abuse.

There is only one addictions treatment program for youth in the province, run by the Addictions Foundation of Manitoba, and detox services for youth are fragmented and can be difficult to navigate. In a statement, the province said several government departments are working on assessing youth treatment models.

“Now, unfortunately, the prevalence of meth, its profound power that it has over people, is really starting to become the drug that’s most readily available and being pushed towards youth right now,” said Manitoba children’s advocate Daphne Penrose.

“It can hide in a domestic violence crisis or a methamphetamine crisis or an opioid crisis. But really what it is it’s a trauma crisis — unaddressed trauma and the need to numb the pain.”

In response to growing addictions issues in Winnipeg, grassroots groups are cropping up to try to fill in the gaps in services and forge social bonds as a salve for so much pain.

It’s at one of these gatherings, in a place that now feels like home to her, where Ramona opens up about her childhood. With no trace of hyperbole or self-pity, her story spills out unprompted, and her mind soon turns to other young people she’s seen “fall through the cracks” — the people she used to hang out with, and others she knows are struggling daily with meth and other drugs.

“You don’t know if they’re safe, you don’t know if they’re eating or if they’re OK. And at the end of the day, that’s what I worry about,” she says.

As she talks, illuminated by an ultra-modern chandelier in the bright, newly renovated Merchants Hotel building on Selkirk Avenue, more people wander in from the dark December night. They take off their coats and set up board games atop long folding tables, settling in like old friends.

Their laughter fills the room as Ramona contemplates possible solutions to widespread meth addiction in her city.

“What really is going to help is acceptance and support and really coming together, just understanding that sometimes it’s not just a problem with the person. Sometimes, it’s problems around them. Problems in the past.”

The answer, she says, gesturing in the air around her, is “more places like this.”

This place, the 13 Moons gathering, began in the summer as an informal drop-in for people from all walks of life to spend an evening together without using drugs. It works closely with the Manitoba Harm Reduction Network under the umbrella of Aboriginal Youth Opportunities. As of this month, it’s become a weekly Saturday night event, welcoming people in off the streets in the heart of the North End, whether they’re sober or not.

On this night, there are about a dozen people here, each for their own reasons. Among them, a Bear Clan Patrol volunteer, a current drug user, and a victim of a meth-related attack sit quietly over a Spirograph and magnetic building blocks.

‘I never thought I would touch it’

She wasn’t looking for it, but there it was.

When she thinks back on her first time using methamphetamine, a Winnipeg teen doesn’t know what she was thinking.

She wasn’t looking for it, but there it was.

When she thinks back on her first time using methamphetamine, a Winnipeg teen doesn’t know what she was thinking.

“It was cut up into a line in front of me and the first time — I don’t know. Throughout my whole life, I never thought I would touch it, but for some reason, I still went back to it for a second time, and I think that really screwed me over,” the 17-year-old said. She asked not to be identified out of respect for her family, because of the stigma drug use still carries.

She’s been clean for seven months, after spending time at Addictions Foundation Manitoba’s Compass program, the only youth-addictions treatment centre currently open in the province. Now, she’s trying to help other young people who’ve fallen into meth.

She knows how easy it is for that to happen.

She’s been volunteering as a peer support at a local phone hotline aimed at helping meth addicts and their families.

“I just want to help people because it’s not worth it. It breaks my heart,” she said. “I just kind of want to be there for people like my family was there for me, because some people don’t have a family like I do.” (Her family was the driving force behind her decision to get treatment.)

Of 317 publicly funded residential treatment beds in Manitoba, only 14 are for youth, all at the Compass program. There are 10 youth detox beds, officially called withdrawal management and stabilization.

Those numbers have remained the same over the past two years, even as meth use steadily increases. The province says it is exploring other youth treatment models and looking at how it can respond to the needs of Manitoba families and Indigenous organizations.

The only other facility to offer residential addictions treatment to youth, the Behavioural Health Foundation, closed its doors to youth in 2016. A provincial government spokesperson said in a statement the BHF youth program had a lack of referrals and its closure didn’t affect wait times for youth trying to get into treatment at Compass.

Raised in St. Vital from a good family, the teen started using cocaine at 15 after a traumatic experience with a sexually abusive male.

“Looking for an escape, because I didn’t care about myself. And I feel like that’s the reason why a lot of young people get into it. They just don’t care about themselves,” she said.

She spent three months using meth. “Those three months were different than any of the two years that I was using drugs.” She stopped seeing a future for herself and started to think using the drug was all she was good for. She had to get sober to realize that’s not true.

“I just want to get the message out there that you can still have a great life, even after doing things like that,” she said.

“They could be anywhere else right now, using substances, but they’re here,” organizer Jenna Wirch says with a hint of pride. “It feels like I’m doing my job.”

She tears up as she talks about the reasons behind her work. She started 13 Moons after her friend, Melissa, died by suicide about a year ago, in the Mount Carmel Clinic parking lot before the building opened one morning.

Melissa was using meth, she was pregnant, and she had no hope left, Wirch says.

“She was scared that CFS was going to take her baby, because they took all of her other babies. She was addicted to meth and didn’t know where to turn, so she killed herself.”

Wirch said she knew she had to do something to bring Indigenous young people together.

“I’ve had to lose a lot of people, but the reason why I do the work that I do today is so I don’t lose anyone — so I don’t lose any other person that’s close to me. I try to make good relationships in the community and provide a safe space so people can come and gather, and so we’re not gathering at a funeral or a wake,” she says.

“Essentially, what we’re trying to do is we’re trying to build a community where people feel connected. The opposite of addiction is connection.”

“The opposite of addiction is connection.” Jenna Wirch

At another table, a 47-year-old woman wearing carefully applied thick black eyeliner and designer boots is taking some time to think. She’d repeatedly caught her daughter injecting meth, and in a desperate attempt to teach her a lesson, to hurt her the way she was hurt as a mother, she took a needle and shot up her own veins.

“The drug just totally numbed me. It took the hurt I was feeling inside for my boys (who were apprehended by CFS). It just totally numbed me. I sat down and I just thought, ‘Wow.’ I couldn’t believe how it made me feel. But I said I was never going to do it again. I just was trying to make a point to her.”

That was about three years ago. She last injected two hours before showing up at 13 Moons. Every time the drug starts to wear off, she’ll cry uncontrollably.

“I can’t get my kids out of my head,” she says.

She’s tried to stop using for good, and she thinks she may be ready to try again.

“It was just too hard for me. So now, I feel like I’m here but I’m not even living,” she says. “I want my life back. I’m tired of living this life that there’s no feelings. I think it’s because of all the pain people are carrying and they’re not dealing with it.”

***

The roots of addiction can usually be traced back to past trauma, addictions workers say. Young or old, users are choosing meth simply because, right now, it’s the cheapest way to numb the pain for the longest amount of time, at least at first.

Elizabeth Stoesz, a rehabilitation counsellor who works with youth at the Addictions Foundation of Manitoba, sees their pain.

“I think the main reason that the youth that I see are trying it is because they’re experiencing high levels of pain and overwhelming problems, overwhelming life circumstances,” she says.

For the most part, Stoesz says the young people she sees aren’t in denial about the effects of the drug. Some are transitioning out of Child and Family Services care and finding themselves on the street. If they’re homeless or at risk of sexual exploitation, meth keeps them awake. They’re trying to survive.

“Some of them feel like it helps them stay more hyper-vigilant or aware. They’ll describe feeling paranoid, but they’ll say, ‘Oh that helps me, because then I can avoid being picked up by police or be really aware of harmful people around me.’”

Exercise, access to recreation programs and structured leisure activities, such as the sports drop-in program AFM started, can go a long way to helping with meth treatment, Stoesz says.

At Ma Mawi Wi Chi Itata Centre, which offers community programs, youth co-ordinator Crystal Leach gets phone calls at 2 a.m. from grandparents worried about children who came to Winnipeg from other communities and went missing.

“They have nobody supervising them. And then what happens is other young people pick them up, or even worse, like gang members or drug dealers, and then they end up entrenched in these things. So a lot of times what we’re doing is we’re just sending them back home, and a lot of the times that changes their life.”

For the past two years, she’s watched as meth use ballooned among young people. It’s become so normal, she’s even seen youth posting photos on Facebook with syringes in their hands.

“I’m noticing how many more people are trying it, how many people are becoming entrenched in it. And then finding out too that the young people, they don’t really have anywhere to go to get help for it, and if they do have a place to go, it’s jumping through barriers and hoops (to get there),” she says.

**

Many are ready — and have been trying — to make a change.

Addictions workers in Manitoba are seeing higher rates of women seeking help for meth addiction, and child-welfare apprehensions may play a role.

At Main Street Project’s Magnus Avenue 27-bed women’s detox centre, meth is starting to surpass alcohol as drug of choice. Alcohol and meth are also the top two drugs at the men’s 30-bed detox centre, but Main Street Project staff say they have noticed an uptick in women using their services.

Many women who turn up at detox have had their children taken into the care of Child and Family Services, but men don’t report the same rates of CFS involvement. Of 569 admissions into women’s detox, 237 had a child or children in CFS care (41 per cent). For men, that figure is only about six per cent (31 out of 558).

“The CFS numbers show just how much more the women lose as far as their children go; this creates further trauma to those women. And it becomes one more pain to numb; one more shame to hide,” says Tahl East, the Main Street Project’s director of detoxification and stabilization. “It’s very, very sad.”

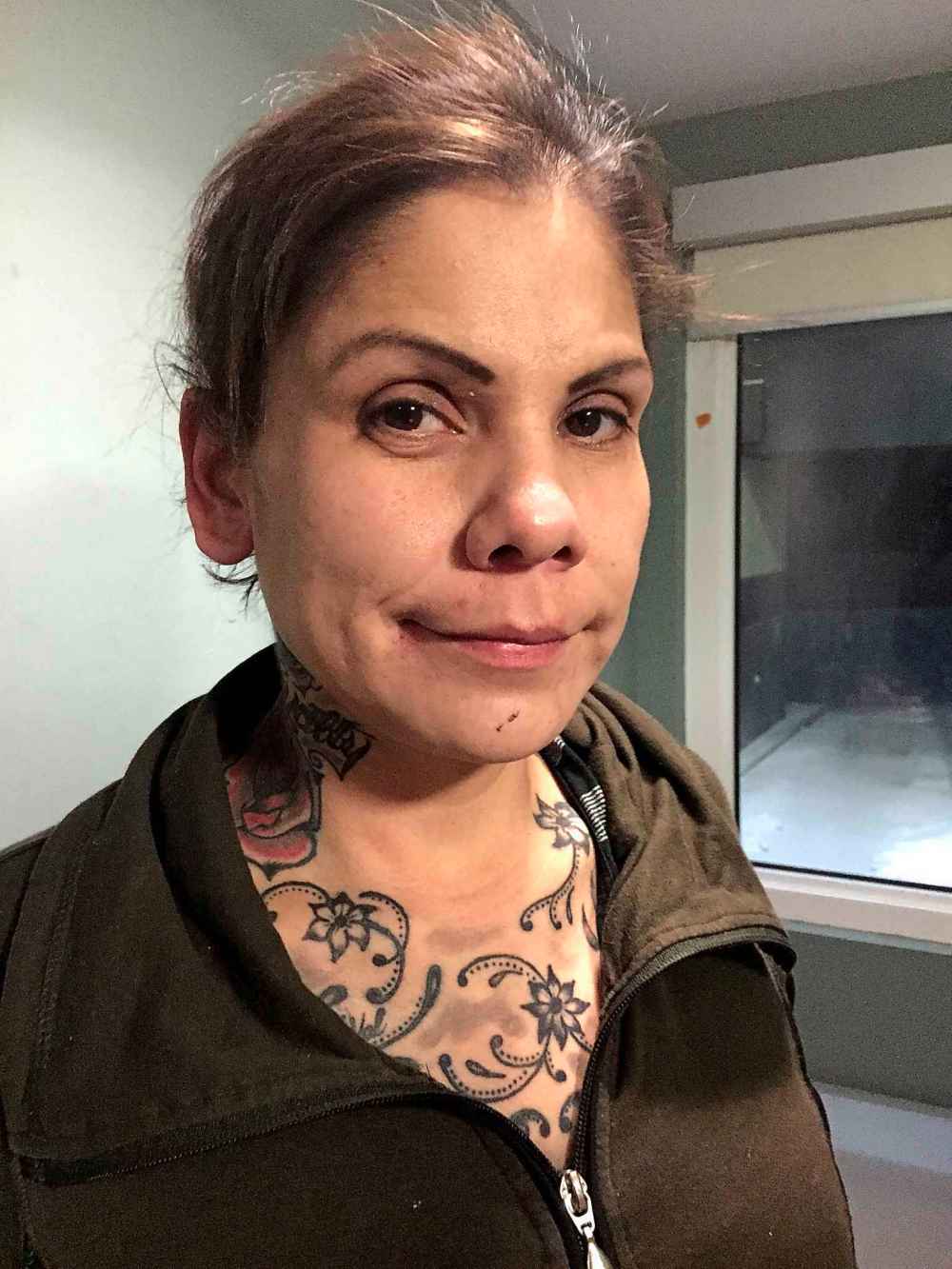

On her final night in the detox before she begins a two-year treatment program at the Behavioural Health Foundation, 31-year-old Taryn Martin pulls up her left pant leg, baring a deep, greyish scar that runs vertically from her inner ankle up to her lower calf.

Carved into her flesh in severe lines, healed over and distorted from infection, is one word: Winnipeg.

In the grips of a meth addiction that made her afraid of everything around her — made her want to die — Martin used an X-Acto knife to mark herself. She was high when she did it. It didn’t hurt until afterward.

“I wrote that in case, if I were to get murdered or taken. At least they would know,” she says.

She’s been in detox four times, and had been here only six days before a long-term treatment bed opened up. She knows she’s lucky to have it, and it’s part of her plan to get clean and see her children again. She started using meth in 2016 after her visits with them stopped.

“You only live once, and I said to myself, I want to be a mom again. I want to hear my kids call my name. I need to be clean, and if I want to be clean, I have to be in a strict place where I’m not allowed to be let out,” she says, explaining she doesn’t trust herself to be out in the world alone. She’s seen too many scary things.

“I don’t want to be remembered as a drug addict, as a no-good mom. I actually want to change while my kids are still young,” Martin says.

“Women have a greater fall than men because of the stigma and because of societal views and norms towards women. So women with any addiction are far more stigmatized than men,” says East.

“They are more open to exploitation and to street work as a form of survival than men. Men also take part in street work and are also exploited, but at much lower rates than the addicted women.”

For 23-year-old Karyn Hastings, using meth made her feel powerful — at first. It was her thing, something she could do to escape from her life as a stay-at-home mom.

“I loved that about the meth, because it made me feel numb,” she says, her bubbly disposition giving way to tears as she speaks. “And I wasn’t able to cry, and I wasn’t able to have this, like, vulnerable feeling in my chest. And then the more I used it, the more angrier I got, and that gave me power.

“It got to the point where I didn’t feel anything at all any more but anger. I was so angry because I just wanted to get high but it just wasn’t doing nothing.”

As she, too, heads into treatment program after an extended stay in detox, she says she’s finding other ways to use her voice.

“I still want to work with children, because that’s where it stems from, is the childhood… It goes way back, this pain we all carry, meth users,” Hastings says.

“I’m going to find me. I’m going to love me, and I want other people to love themselves, too.”

— with files from Jessica Botelho-Urbanski

katie.may@freepress.mb.ca

Twitter: @thatkatiemay

Withdrawal management/stabilization (detox)

2016: 68

2017: 68

2018: 80

Primary residential treatment

2016: 337

2017: 337

2018: 317

Second-stage treatment/supportive housing

2016: 195

2017: 198

2018: 198

There are also 99 privately-funded treatment beds in the province.

Youth treatment beds

(numbers included in total numbers above)

Withdrawal management/stabilization (detox)

2016: 8

2017: 10

2018: 10

Residential treatment:

2016: 46

2017: 14

2018: 14

— source: province of Manitoba

Katie May is a multimedia producer for the Free Press.

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.

History

Updated on Thursday, December 20, 2018 11:41 AM CST: fixes typo, adds factbox