Burned into memory Thousands of Winnipeggers watched helplessly 50 years ago as the St. Boniface Basilica -- the centre of life in the French community -- was destroyed by fire

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 20/07/2018 (2700 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

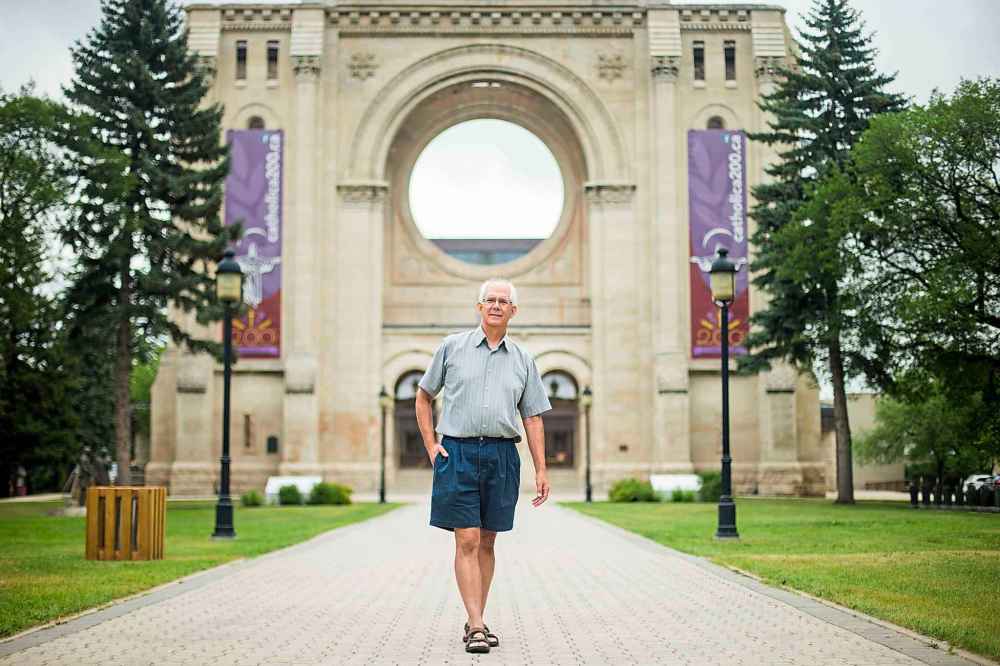

Fifty years ago today, Philippe Mailhot stood in the cemetery in front of St. Boniface Basilica and watched as the beating heart of the community went up in flames.

That was the day the 60-year-old basilica — the fifth Roman Catholic edifice built on the site since the first church rose in 1818 — was destroyed in one of the most significant fires in Manitoba’s history.

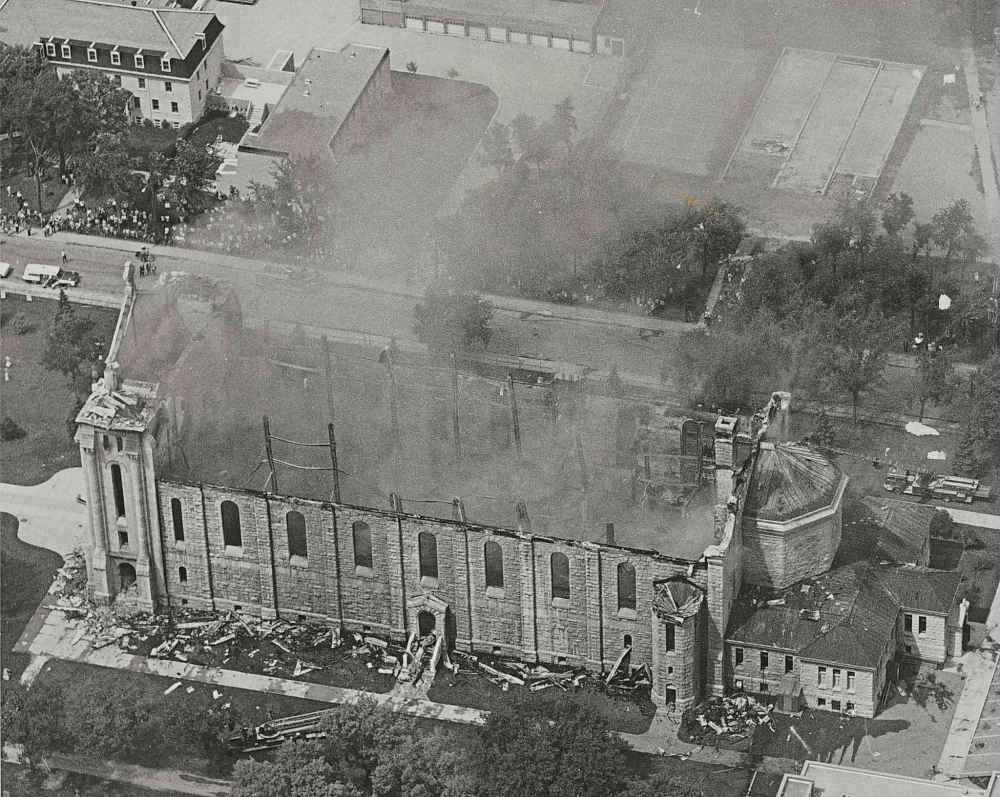

In less than two hours on July 22, 1968, the symbol of the Roman Catholic Church’s 150-year history in St. Boniface was reduced to a pile of smouldering rubble encased in a charred shell of stone.

“I was 13 years old and visiting my cousin Claude who lived on Goulet Street,” Mailhot, who grew up to become a historian and director of the St. Boniface Museum for a quarter-century, recalled Friday morning during a tour of the ruins, inside of which a new cathedral opened in 1972.

“We were going to go swimming,” Mailhot, now 63, said. “It was a very hot summer day. We were just leaving the house when my aunt Eveline came running up shouting: ‘The cathedral is on fire! The cathedral is on fire!”

‘I was told to call in everyone’

It’s a moment former St. Boniface Fire Department member Art Desmet will never forget.

“I received a call on 999, that there was a fire in the rectory at St. Boniface Cathedral,” the 80-year-old said this week.

“I was told to call in everyone,” he said. “I was calling people who were off duty, guys who were on vacation. We needed everyone.”

It’s a moment former St. Boniface Fire Department member Art Desmet will never forget.

He was acting district chief on July 22, 1968, when the 999 emergency phone line (it later became 911) rang at 12:08 p.m.

“I received a call on 999, that there was a fire in the rectory at St. Boniface Cathedral,” the 80-year-old said this week. “I received the call from someone working in the cathedral.”

Desmet immediately began calling for fire crews to rush to one of the most prominent — and beloved — buildings in St. Boniface.

“I was told to call in everyone,” he said. “I was calling people who were off duty, guys who were on vacation. We needed everyone.”

Even firefighters who were at their cottages an hour or two out of the city rushed back as soon as they heard about the fire, he said.

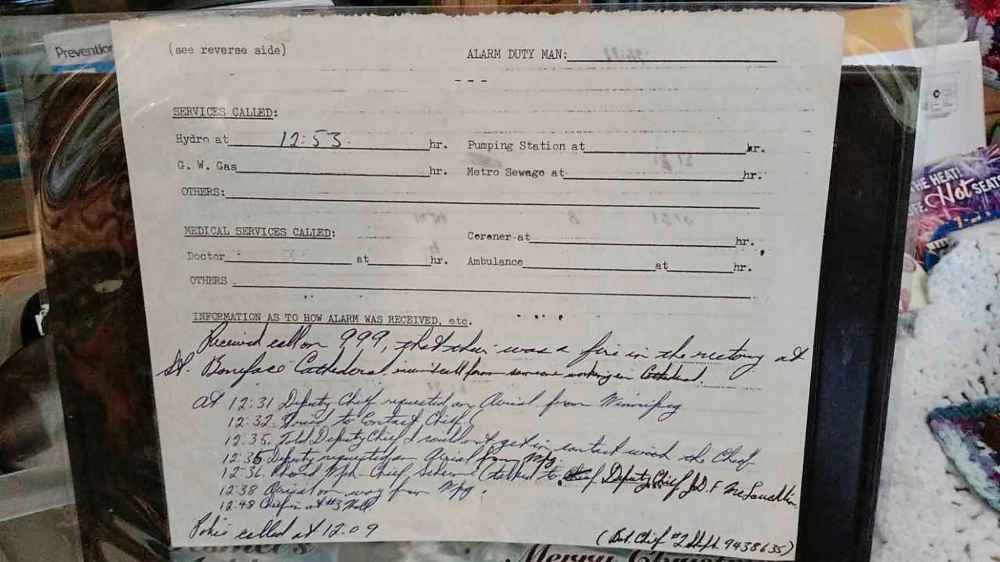

Desmet still has copies of the alarm report from that day — pages he rightfully calls “history.”

They show the first alarm was called out at 12:08 p.m., followed by the second at 12:13 p.m. The deputy chief got to the scene at 12:09 p.m., the police were called at about the same time, and by 12:31 p.m. the deputy chief was calling Desmet to request an aerial ladder truck from the neighbouring Winnipeg Fire Department. (The two departments would later meld in 1974, as part of the formation of what is now the Winnipeg Fire Paramedic Service.)

Desmet’s notes show he first tried calling the St. Boniface fire chief to make the request to Winnipeg, but when staff couldn’t locate him, they called Winnipeg anyway and, at 12:38 p.m., the aerial truck was on its way.

Media accounts at the time show the aerial truck was delayed — and had to detour to get across the Red River — because so many Winnipeggers were rushing across the Provencher Bridge to watch the blaze.

Firefighters on scene knew the building was doomed when the cathedral’s twin spires fell into the interior of the basilica, followed by the explosion of the large stained-glass window at the front.

Desmet said he went home after his shift, and had just enough time to eat dinner before he got the call to return, this time to the fire.

“Everybody was working — there were no lazy guys there,” he said. “I was there when the window blew out, but I was so busy I didn’t see it… But when the big front, round window let go, it was pretty devastating.”

Desmet said workers did a good job retaining the old cathedral walls when they built a new rectory inside the ruins at 190 Avenue de la Cathedrale, but it also brings back memories for any firefighter who was there five decades ago.

“Your heart pumps a little more today when you go past it,” he said.

kevin.rollason@freepress.mb.ca

Which is when Mailhot and his cousin hopped on their bikes and pedalled like mad to the cemetery in front of the historic cathedral, joining a throng of thousands gathered to watch the out-of-control blaze that began in the rear of the church’s attic and spread quickly up its twin turrets.

“What I remember was this ball of flame in the roof basically chewing its way toward the bell towers at the front,” he said, pointing at the top of the stone ruins. “This was one of the tallest buildings in the city. It was the equivalent of a six-storey building.

“We parked in front of the cathedral and the crowd just kept getting bigger and bigger. There were thousands and thousands of people. It was quite the crowd.”

Mailhot doesn’t remember much about the smoke or the heat, although reporters at the time claimed you could feel the fire at least two blocks away and the size of the group watching made it difficult for firefighters to get equipment to the scene.

“A firefighter told me they couldn’t get trucks over the Provencher Bridge or the Norwood Bridge because it was just gridlocked,” Mailhot said. “Nobody was moving. The cars were just stopped and people were watching the fire.

“Then smoke started coming out of the bell towers, which started to burn. When the bell towers collapsed into the church, there was a collective groan from the crowd. They had hoped if they could save the towers, they could save the church. Bell towers are designed, in the event of a fire, to collapse inside a church.”

In the years to come, Mailhot was told that had the cathedral’s massive stone facade fallen forwards, he and his cousin could have been flattened.

“As a 13-year-old know-it-all, I figured ‘this place is a goner,'” he said. “Thirteen-year-olds don’t have long attention spans. After the bell towers went down, we went swimming.”

The fire began at about noon and is believed to have started as the result of a carelessly tossed cigarette from one of the workmen repainting and repairing the basilica’s roof.

By 1:10 p.m., the turrets went crashing into the building, and the bells, which had been brought over from England in 1840, also plunged into the basement. After fire destroyed the third cathedral in 1860, the bells were sent back to England for recasting and later returned to the church.

When the smoke finally cleared, all that was left was the facade, the charred stone walls, the marble altar and the sacristy. The fire had consumed the spiritual and cultural heart of St. Boniface, then a separate city.

In an editorial the day after the blaze, the Free Press opined: “Not just the city of St. Boniface but all Manitoba and indeed all Canada suffered a grievous loss in the destruction by fire on Monday of St. Boniface Cathedral.

“It is particularly heart-rending that the disaster should have struck when the city had just celebrated its 150th anniversary as a community — the community from which Christianity spread throughout Western Canada and of which the Basilica was the focus.”

Walking through the cemetery Friday, Mailhot pointed out a monument paying tribute to all the churches built on the site, erected just six days before the basilica was gutted by fire.

On that sweltering day in July 1968, St. Boniface Archbishop Maurice Baudoux spoke with Free Press reporters as he watched flames lick through his beloved cathedral.

“Sentimentally, it is the greatest loss that can be imagined,” he said, quietly. “We had been thinking of the possibility this might happen… but one cannot imagine that it has happened.”

As the archbishop walked through the crowds, it was reported that elderly parishioners and small children rushed up to him to offer comfort or express their grief.

While the archbishop and the 13-year-old version of Philippe Mailhot were watching the fire, reporter Michele Veilleux was interviewing community members, who were heartsick about the loss of an institution they held dear.

“For me, it’s my whole life,” said a 70-year-old sister of the Order of the Holy Names of Jesus and Mary, who would not reveal her name.

Interviewed in French, the sister explained: “I was baptized in the previous church that was demolished to build this one, but I made my first communion in the basilica.

“My father’s and mother’s funeral ceremonies were held here and they were buried in the shadow of the cathedral. Our family pew was just opposite that door… it’s as if it was my own house that was burning.”

Once the fire began in the attic, nothing could have been done to stop it from gutting the whole structure, St. Boniface fire chief Emery Proulx told the Free Press’s Ron Campbell the day after the tragedy.

“If you go back into the history of fires in these churches, once a fire starts in them, they are usually destroyed,” he said, because unlike an apartment block or a house, there are no partitions or walls inside to contain the fire. “It was so vast in there, there was no way you could have stopped it.”

Mailhot said the community was determined, even if it took 100 years, to see their church rise from the ashes.

“It was 1968 and organized religion was more important than today,” he noted. “It was the heart of St. Boniface. The city’s tagline was: ‘St. Boniface: the Cathedral City.’

“St. Boniface is the mother church of Catholicism in Western Canada … In the 1960s, if you were a French-Canadian, you were still going to church. The church was still a pretty important player. The St. Boniface Cathedral was the jewel in the French Catholic sense of place in Western Canada.

“It’s still considered a cultural centre for the community. I’d encourage everyone to go to the St. Boniface museum and learn about this cathedral… it’s still one of the hottest tourist destinations in the province. Tens of thousands of people visit it every year. The new cathedral is a remarkable facility.”

And it no doubt has smoke detectors.

doug.speirs@freepress.mb.ca

Doug has held almost every job at the newspaper — reporter, city editor, night editor, tour guide, hand model — and his colleagues are confident he’ll eventually find something he is good at.

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.