Meaning amid the misery

Well-known Winnipeg family turns devastation of drug-abuse loss into determined drive to help others

By: Randy Turner

Posted:

Last Modified:

By: Randy Turner

Posted:

Last Modified:

Advertisement

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 26/05/2017 (3123 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

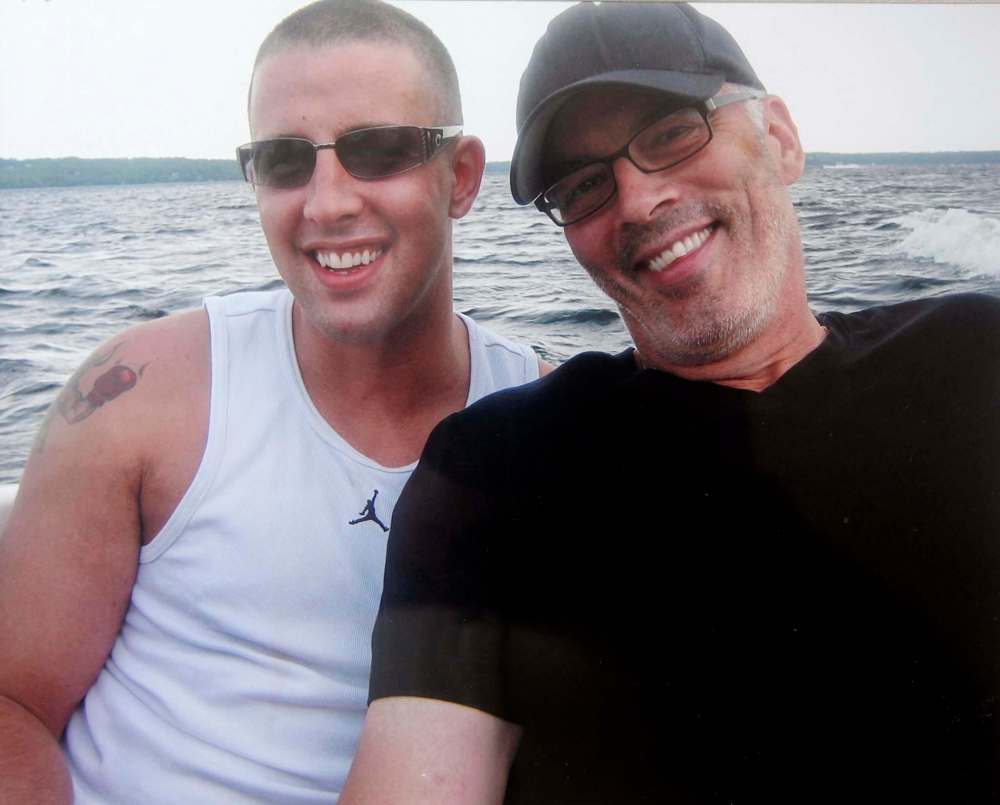

As a boy, Bruce Oake was a precocious kid. He was outgoing, friendly and impulsive.

“He spoke baby gibberish for a long while, and one day he just started talking,” says his father, Scott Oake. “And he never shut up, ever after.”

As a teenager, Bruce was a prankster. He and his brother, Darcy Oake, would play a game where they’d walk down the street holding hands to see who would let go first.

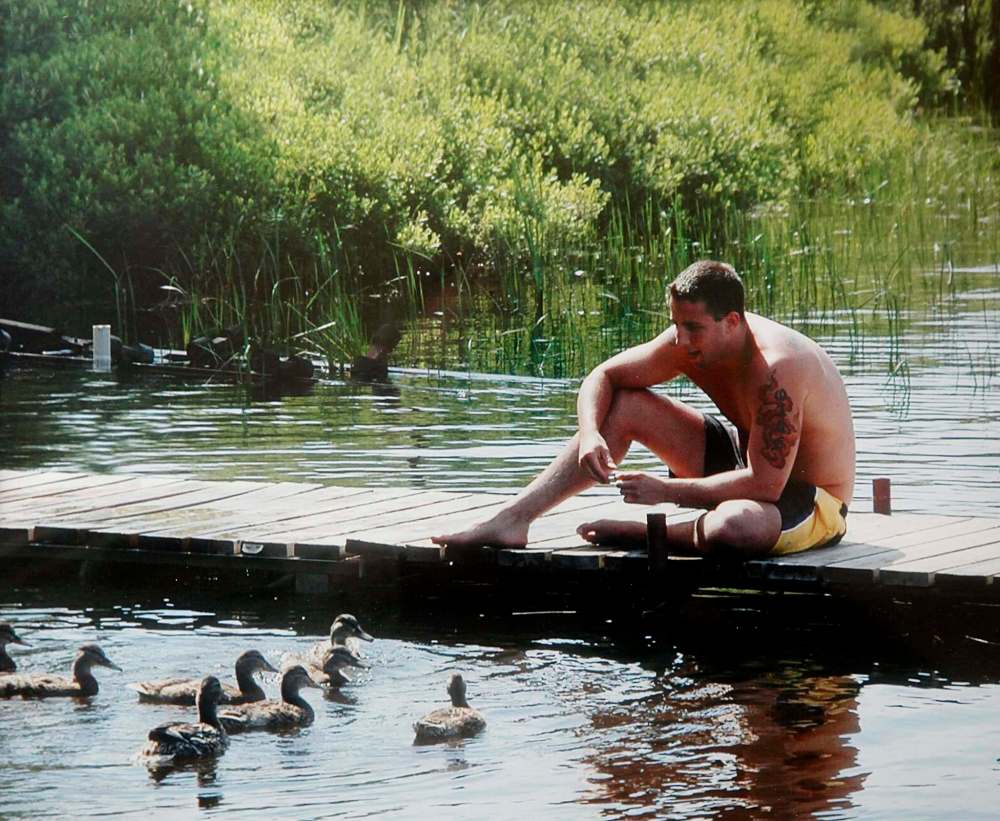

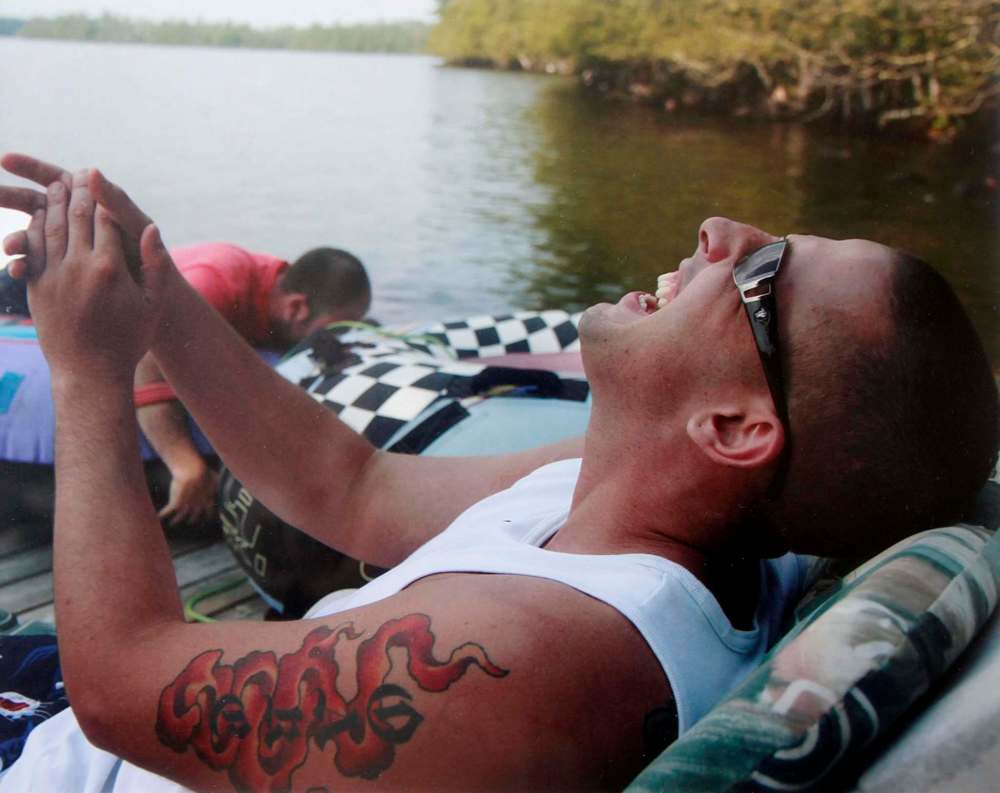

“If it wasn’t fun, he wasn’t interested in it,” says Bruce’s friend Bret Olson. “He never wanted the day to end and couldn’t wait for it to get started again. That’s what stands out for me: just that tireless, ‘What are we doing next?’”

As a young man, Bruce had a booming voice. He craved to be around people. He was charismatic, persuasive and fearless.

“He had this way of connecting with people so easily,” his brother says. “It was effortless. It was infectious.”

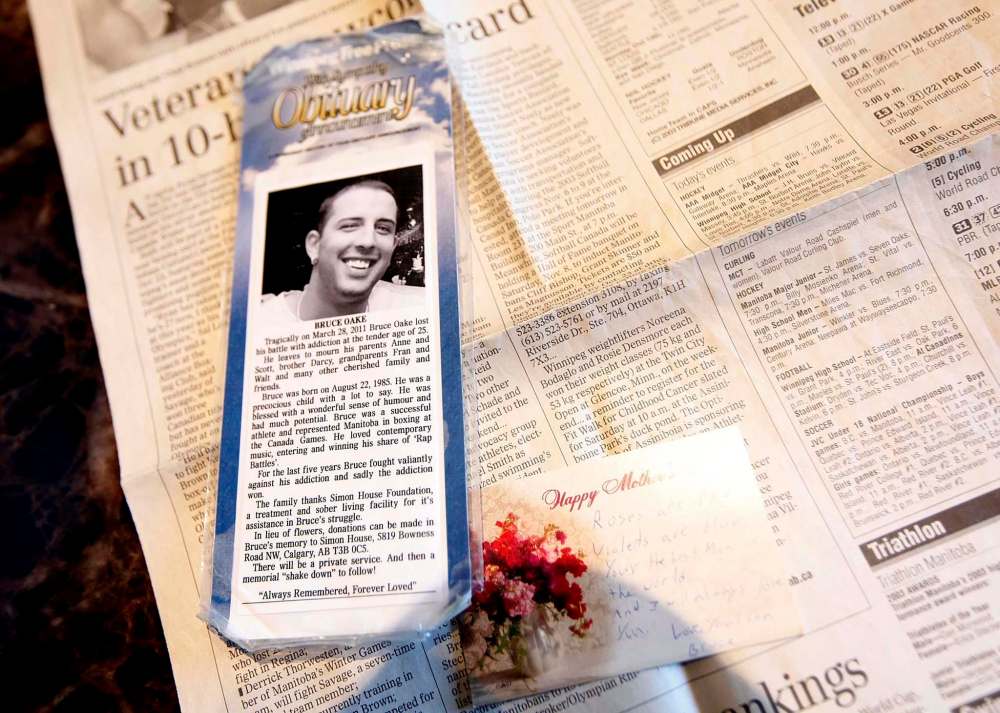

At the age of 25, Bruce, by then a heroin addict, died alone on the floor of a washroom stall.

It’s not an easy story for his father, a longtime fixture on Hockey Night in Canada broadcasts, and his brother, a world-famous illusionist, to tell. But they tell it unflinchingly, if only because they learned the hardest way possible drug addiction doesn’t discriminate and that there are thousands of other family members out there experiencing the same agony.

They’re determined to fund a $14-million drug treatment centre in Winnipeg in Bruce’s memory.

After years of heartbreak, late-night distress calls and watching him go from an exuberant, carefree kid to a 140-pound junkie and drug dealer, the family’s motivation is straightforward.

“To make his life mean something,” Scott says, “is what is driving us.”

Where to begin?

How about the night when the police arrived at their suburban home, concerned about violent drug dealers looking for Bruce.

The moment when their lives would never be the same again.

Anne Oake was in Halifax in February 2007 when her son Bruce called. He’d been beaten up, he said. His hand had been broken, his car stolen.

For a few years, Anne had been fearful her oldest boy had been involved with drugs. It wasn’t just mother’s intuition. She’d caught him in lies. She’d sometimes trailed him when he left the house, his reasons vague and suspicious.

“I’m not a junkie,” Bruce insisted, “but I have a problem.”

He had a lot of problems. The gang members who broke his hand wanted the $25,000 they claimed he stole from them. So it was decided the Oake brothers would stay at a hotel until their parents could return from Nova Scotia.

“But when we got home, we realized he was a junkie,” Anne recalls. Bruce, who only a few years earlier had competed in boxing at the Canada Games, was rake-thin; his face was drawn.

Police were concerned the gang members, who knew where the Oakes lived, would show up looking for Bruce. So they sat on watch at the kitchen table.

Meanwhile, Anne was giving Bruce a prescribed dose of Oxycontin every four hours to keep him from going into withdrawal.

“I was a wreck,” she says. “It was just horrifying. I felt like I had (post-traumatic stress disorder).”

Tension was spiked. During the stakeout, Darcy arrived unannounced from a magic club meeting through the garage door.

“And these guys (police) jump around the corner ready to pull their guns out,” he recalls.

Scott is quick to acknowledge Bruce wasn’t some innocent bystander. He was skimming from the drugs he was selling to feed his own opioid habit.

Imagine an upper-middle-class life — successful parents, two handsome young boys and a cottage-at-the-lake, home-in-Linden-Woods existence — shattered in one night with a mother feeding her son drugs and cops at the kitchen table.

“That,” says Scott, “was the start of the odyssey.”

The Oakes decided immediately to send their son to a private rehab facility in Ontario. It was a lot of money — $25,000 for 40 days. But they could afford it.

After all, Scott had for years been a household name on CBC, a Gemini-winning sports broadcaster with some 20 Stanley Cup playoffs and 15 Olympics on his resumé. They weren’t rich, but they had means.

They never forgot the words of advice they were given by the rehab doctor when Bruce was admitted: “Prepare yourself for failure.”

“We dismissed it because we were a family that was doing everything right to address this problem,” Scott recalls. “He was going to go to detox. He was going to go to this private facility outside of Toronto. And this was going to fix it. And we were all going to go back to our happy little lives. How could this not work?”

Bruce graduated “with flying colours.” But given the circumstances of his departure from Winnipeg, his parents believed the safest place for recovery was far from home.

They sent him up in Halifax, where they had family; Scott was born in Sydney, N.S. They got him an apartment. Bruce’s grandfather found him a job at a transport company.

It was April 2007.

“He had it all in the palm of his hands,” Scott says. “A fresh start.”

But any expectation of going back to their “happy little lives” was soon shattered. Bruce lost his job. He turned to heroin, an even harder drug. The next year included eight trips to detox and another two rehab stints.

During Bruce’s second attempt at rehab in the fall of 2008, Anne travelled to Halifax and walked into her son’s apartment. There was no furniture and no curtains on the windows. Needles were strewn everywhere.

“The apartment that we’d rented for him was stripped bare,” she says. “He’d sold everything. I just wanted to curl up in a ball.”

At the time, Scott was on the other side of the world, covering the Summer Olympics in Beijing. Anne kept what she had found from her husband, knowing there was nothing he could do from China.

It’s worth noting the Oakes had, for several years, pleaded with Bruce to straighten out his life. While he loved to write and perform rap music — had even won a few contests in Winnipeg — it wasn’t a real job.

Scott would often return home, find his son in the basement again, and sarcastically ask, “So, has anyone come down here and offered you a job today?”

“We were on him every day,” he adds.

But their son was clever and deceptive and constantly used those skills to pry money from family and friends. Guilt was also a go-to ploy.

One day, Bruce called from Halifax to plead for food money. He insisted he was eating cat food.

His father didn’t bite. He told his son, “Eating cat food, eh? I hear there’s protein in that.”

Then, Scott hung up the phone. It was a game effort to show resolve, but inside, his heart was breaking.

“It’s an impossible balancing act,” Scott says.

Adds Anne: “We got so much criticism. People would say, ‘All you’re doing is enabling him.’ And I would say, ‘You tell me where the line is between parenting and enabling.’

“We’d say, ‘Maybe he’s just $100 away from getting it right. Maybe if we just pay this month’s rent he’ll figure it out.’”

Two days after the cat food conversation, Bruce entered detox while his parents scrambled to place him in a long-term rehab facility in Calgary called Simon House.

If there was one blessing, it was that despite all the dashed hope and omnipresent fear, the Oakes, who met in Winnipeg on a blind date in 1977 and married three years later, were always on the same page.

Darcy still marvels at how his parents coped.

“Oh, there’s no words in the vocabulary to describe it,” he says. “It’s one of the worst things to ever see your child go through. It’s that weight.”

For Anne, it was simply survival.

“I’m not sure how we even got through that,” she says. “You’re just sort of going… you’re in a panic zone constantly. Every day, you have a knot in your stomach. Every time the phone rings, you’re thinking, ‘Oh, God, what happened now?’”

Adds Scott: “If the phone rang around here late at night, your heart would go right up into your throat, if not past your throat to your brain.”

All the while, Scott continued to do his job on live TV, sometimes right after he’d learned Bruce had left rehab or been beaten by gang members.

“I was somehow able to compartmentalize it and get through the night,” he says. “I don’t know how I did it, but I just sucked it up and did it. But the whole time I was worried about him. It was a horrid time, though. It was constantly on my mind for three years.”

Meanwhile, Bruce and Darcy — who, in their late teens, become best friends in addition to being brothers — remained close.

“It was frustrating to me, and I’d get mad at him,” Darcy says. “But I remember a comedian saying one time it’s the only disease you get yelled at for having. You can get mad at this person and tell them to stop doing it, but they can’t, and they’re not going to if they don’t want to. And a lot of times, if they want to, they still can’t.

“So it’s a whole vicious cycle. You don’t know how to react. There’s no guidebook for it.”

Did he ever give up on his brother?

“I don’t think you ever really lose hope, because that’s all you’re hanging on to,” he says. “I’d never write off someone in my family. It’s all we had.”

In September 2008, Scott flew to Halifax to take his ailing son to Calgary’s Simon House, a program that keeps patients for up to three years.

The effects of the drugs had consumed Bruce. He weighed about 140 pounds.

“He’s a good-looking boy, and he looked like death warmed over,” Scott recalls. “It was like a prisoner evacuation. I never let him out of my sight.”

The counsellors at Simon House told the Oakes not to contact their son for a few weeks. They happily complied.

“Those were the best times of our life,” Scott says. “Because he was safe.”

But the realities of addiction soon returned. While at Simon House, Bruce failed a drug test. That was grounds for expulsion for at least one year. What followed was the same cycle of detox and rehab.

Even while holding a job selling health-club memberships (Bruce was one of the company’s top 10 salesmen in the country), even while continuing to win rap battles in Calgary — the drug use escalated.

Over the next two years, Bruce became more morose. The once-talkative, energetic boy who couldn’t wait for the next adventure told his mother, “I’m not going to have a long life.”

In spring 2011, Bruce was finally convinced to enter detox. Again. Simon House was prepared to accept him.

Bruce was there just six weeks before he was caught using again. He was ejected on March 22. Six days later, he was found unresponsive just before midnight, slumped in a bathroom stall of a sports bar not far from his apartment.

Scott and Anne were visiting family in Nova Scotia when they got a call early the next morning from Winnipeg police. Before the grief kicked in, Anne remembers calling her only living son to deliver the awful news.

It’s was 7 a.m. in Winnipeg. She only got out one word. “Darcy…

“He said, ‘Mom, no, no, no!’ I didn’t even have to say anything.”

It’s May 2017, and Darcy is standing on the stage at the Burton Cummings Theatre, arms spread wide.

“They don’t make theatres like this anymore,” he said. “I mean, Charlie Chaplin performed here.”

Darcy is 29 now, six years removed from the early morning call from his mother that altered his life in so many ways.

In 2011, Darcy was mostly doing one-night gigs where he could find them. Sure, he was making his way. But the death of his brother brought an urgency to his long-held dream of becoming a world-class illusionist.

He began taking jobs that kept him on the road as long as possible. He travelled the world — Europe, Asia, Scandinavia.

The rest, of course, is history. Darcy landed an audition with Britain’s Got Talent in 2014, making it to the competition final. After more than a decade working on his craft — beginning in the basement with an audience of none — he became an overnight sensation.

In the last two years, he’s done one-man shows for billionaires at their palatial estates; the French Alps, Montenegro, Paris. There was a show for the president of Kazakhstan.

Oh, and the show at Windsor Castle for the Royal Family, which explains the picture of Darcy meeting Queen Elizabeth II that’s hanging on his apartment wall.

“I’ve seen some places that I didn’t even know existed,” he says.

“It’s crazy to think about it now. It’s six years since Bruce (died) now. I threw myself into booking anything that I could. I never really looked back. This tragedy happens and the only way for me to sort of get by is to be focused on this as much as I could be.

“Looking back on it now, it’s a correlation, completely. The weight never goes away. You live with it, but it’s how you live with it. I’d still be doing this, I just don’t know if I would have felt the need to go head-first, as hard as I could, for as long as I can. Still.”

Are there times when it doesn’t even feel real?

“I don’t know if it ever really does seem real,” he says. “It’s weird. I still have moments when stuff happens, and that’s when I would call him. That’s the hardest for me. Or when I see one of my best friends mess around with his brother, like we would.”

Life is a mystery, sometimes. He calls his career passion “accidental.” When he was eight or nine years old, his father showed him a so-called card trick at the kitchen table. Scott fanned out a deck in front of his boy and said, “Pick one.”

After fumbling around with the cards, the father produced one and said, “Is this it?”

The boy’s eyes grew wide. It was! “I was like, ‘What? How did you do that?’”

Turns out, Scott didn’t know how he did it. It was a complete fluke. A one-in-52 chance, to be exact. But his son was hooked — for life.

And it’s not lost on Darcy that his success in the wake of his brother’s death has allowed him to be an integral part of the family’s efforts to establish the Bruce Oake Foundation with the goal of building a $14-million recovery centre.

From June 6 to June 9, he’ll perform four shows at the Burton Cummings Theatre; the proceeds will go to the foundation. True North Sports and Entertainment, which owns the venue, isn’t charging rent.

If they sell out, the four shows could raise $500,000.

“There’s more to this than we can ever explain,” Darcy says. “I mean, I don’t want to sound like a crazy hippie. But it’s the way things have unfolded in my life and the way I see things. All of this has to mean something.

“I’m in a position now where we can make this (treatment centre) happen. We have to make this happen.”

After six years of dogged determination, his family’s dream is slowly taking shape. They are close to acquiring a piece of land large enough to house the 35,000-square-foot facility.

Accounting giant MNP, legal firm MLT Aikins and MMP Architects are providing their services, pro bono. The project has been pitched to the city and provincial governments, along with several potentially large donors, and the response has been positive. In the last six months, Scott and Anne’s vision is getting close to reality.

“We had a lot of periods where we were discouraged, thinking this would never get down,” Scott says. “But it’s beginning to feel like we have a good chance to get to the finish line, too.”

He says the current crisis involving fentanyl and other deadly opioids only underlines the need for a long-term drug recovery centre in Manitoba.

In the last four years, there were 61 deaths in Manitoba directly or indirectly caused by fentanyl, the province’s Chief Medical Examiner’s office says, with more autopsy reports to be completed.

“People are dying now,” Scott says. “Here’s the essential problem: we’re caught in the hard grip of this horrid opioid crisis that’s not going to get any better unless treatment is made available for the percentage of addicts who can’t afford it. I’m not sure what that number is, but I’m guessing 95 per cent, maybe.

“If it costs $100 dollars a day for treatment, for most addicts that might as well be $1,000 a day. They don’t have it.”

Other treatment centres have waiting lists that can be up to six months.

“It’s pretty hard not to conclude that we’re leaving a generation of addicts out there to die,” he says.

The Bruce Oake Foundation would be run by the Calgary-based Fresh Start Recovery Centre, founded in 1992, which boasts an 81 per cent group completion rate and a 55 per cent success rate of continuous abstinence-based recovery at one year.

In March, the Alberta provincial government announced it would spend $7 million to nearly double the number of recovering addicts who can be housed at Fresh Start, a 50-bed facility with another 20 beds for men who have completed the treatment program.

Like Fresh Start, the planned Oake recovery centre will be a three-phase program. Phase 1, which is intensive treatment, will last three to four months. Phase 2 involves integration back into the community and finding a job, and patients will be able to continue living in the facility. Phase 3 will offer the option of continuing to live at the centre in a safe environment, with restrictions, for up to three years.

“Twenty-eight days, 45 days, 90 days is not enough,” Scott says.” We call those rinse and wash and spin-dry stays.”

There would be no cost to addicts if they can’t afford it, and no one will be turned away, he says.

Ross Rutherford, a former CBC colleague who has known the Oakes for 37 years, says the project has become a mission for the family.

“I can’t imagine what they’ve gone through,” says Rutherford, whose daughters Courtney and Stephanie grew up with the Oake boys.

“Losing a child, it couldn’t be any worse. But I know that they wanted to do something so Bruce’s death means something. And I think they’ve done it the right way, too. They’ve been quietly working under the radar, talking to the right people, gathering information, doing business plans. They’ve done it all.

“It tears your heart out because you’re listening to someone who tried everything they could. They did everything. And in the end, the drugs won out. So for them to say, ‘We’re not going to let this death be in vain,’ is their testament to say, ‘How can we change this?’

“If they can stop one child from losing his life, that would be worth it for them.”

In fact, some money already raised has been used to help a half-dozen addicts find treatment.

“The bright side of all of this, I think they may get it someday,” Rutherford says. “It might not be sooner than later, but I believe it will happen. If not, they can always have a foundation set up that can help other kids get into drug-treatment programs.

“So Bruce is alive and well in a lot of people. In the meantime, they can help some kids get drug treatment. That’s all we can hope for.”

An urn containing Bruce’s ashes sits on a table in his parents’ living room.

“He hated being alone,” Anne says. “We didn’t want him in the ground.”

Anne sets fresh flowers by the urn once a week. After Bruce’s death, she took a year off work as a palliative-care nurse and “pretty much never got out of bed.”

“I just felt terrible all the time,” she says. “You can’t explain it to anybody. It’s like your heart’s been ripped out.”

And now?

“I have good days and bad days,” she says. “I’m a lot sadder than I used to be, for sure. It doesn’t take much to get me upset. It’s still fresh to me every day.”

She’s determined to remember her son for more than his addiction, such as the times her boys would make her laugh with their hijinks.

Darcy is no different. There is a tattoo sleeve on his right arm, with a guardian angel on his shoulder hovering over two cherub brothers beneath. The dates of Bruce’s birth and death and one of his rap lyrics are inscribed: “The only time I heard the truth is when God said it.”

But the memories he holds on the inside are visible to him, too. Like that gag about holding his brother’s hand in public.

“That’s what I love to do now the most, reminiscing,” he says. “The memories can never be taken away, right? That’s what you have. What good is it to keep them locked in and never share them? It’s therapeutic to me.”

The lives of Bruce’s friends changed, too.

Derek Thorwesten boxed with young Bruce at national events, including the 2003 Canada Games. They trained in a building that is now his office with Canada Post, at Panet Road and Nairn Avenue.

“That’s always in my head,” says the 32-year-old supervisor.

So is the issue of drug overdoses.

“People need to be aware of the problems out there,” Thorwesten says. “It’s affecting way too many people. I never thought I would ever say a friend of mine passed away from a drug overdose. When it happened, it really opened my eyes to the issues that are out there.

“That family is special,” he adds. “Not making drug addiction a taboo subject like it often is. They’re open about it, upfront and honest. That’s what we need.”

Bret Olson is Anne and Scott’s godson. Now 35, the regional manager of two Joey’s restaurant locations has partnered with Vertuity Mortgage to raise more than $100,000 for the foundation through charity golf tournaments.

“It’s exposed me to a world that’s really easy to ignore unless you’re a part of it,” Olson says. “It’s opened my eyes to some of those things I can support instead of pretending they don’t exist.”

A few years ago, Olson travelled with Scott, Anne and Darcy to Calgary, where they met some of Bruce’s friends, counsellors and roommates.

“I think they wanted to put the pieces together,” he says. “I mean, it was so abrupt. I think they were trying their best to be with him in those last few minutes to try and figure out what his mindset was.”

But the memory of Bruce that Olson clings to was the day he visited his friend at Simon House in Calgary. He was taking Bruce out to lunch.

As he entered the centre, Olson said he could hear “this high-pitched Michael Jackson-type singing.”

“And when I went in the room, sure enough it was (Bruce) on the couch with his head back, singing like Stevie Wonder,” Olson recalls. “For me, there’s something in that moment that I’ll probably never forget because you’d just have every reason to be unhappy in a place like that. But there was a certain part of his personality that no matter what situation he was in, he was that guy singing a song on the couch among these other people trying to rehab.

“Like I said, if he wasn’t having fun, he wasn’t interested.”

Scott still wears his son’s flip-flops. He carries a beat-up photo of Bruce in his wallet.

Known for his desert-dry wit, Scott punctuates much of a 90-minute interview with self-deprecating and humorous asides. It’s one way of dealing, he later explains.

But when asked about how his son’s death has changed him, his voice cracks, just a little. You see, long before the odyssey with their lost son began, Scott and Anne began volunteering at the Siloam Mission.

At least once a week, the guy usually interviewing Sidney Crosby or Connor McDavid could be found pouring juice for the homeless at the shelter, making sure to sit down at a table to shoot the breeze before he left.

“I’ve always looked at the patrons as someone’s son or daughter,” he says. “But that sensitivity is heightened now. I mean, I’ve thought of this a lot. No one grows up wanting to be a drug addict, right? I don’t think any kid’s ever said that.”

It’s also why the couple never leaves the house without loonies or toonies in the car, just in case anyone approaches them while they’re idling at a red light.

“We both have trouble going past a homeless person or someone asking for money,” Scott says. “Because we look at those people, especially the young ones… could have been Bruce. We’d like to think his safety net was bigger than that, but… that’s where life might have led him, despite our best efforts.”

From the beginning, the Oake family was determined not to bury their son, nor his battle with addiction. And it’s never been easy. But the story has another chapter to write: in death, Bruce helping to save others.

“It’s a hard story to tell, and we’re drained after,” Scott says, “but it’s worth it.”

randy.turner@freepress.mb.ca

Twitter: @randyturner15

Randy Turner

Reporter

Randy Turner spent much of his journalistic career on the road. A lot of roads. Dirt roads, snow-packed roads, U.S. interstates and foreign highways. In other words, he got a lot of kilometres on the odometer, if you know what we mean.

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.